- Home

- Unemployment

- Technological Unemployment

What is Technological Unemployment?

Technological unemployment is an increasingly important, and somewhat contentious, issue in economics that relates to the loss of jobs that occur when new labor-saving technology is adopted by a business or industry. It results in a specific type of structural unemployment for the displaced workers affected by it.

The phenomena of machines replacing workers has been around since the earliest days of capitalism, and plenty of workers have indeed suffered real financial hardship because of it, but the overall net benefits to society that come from technological progress are undeniable.

The standard of living that people in the developed economies enjoy, compared to previous generations, are enormous and should never be overlooked. However, the historical concerns over technological unemployment will gain a great deal more attention in the decades ahead, because there will soon come a time when advanced robotics, artificial intelligence, nanotechnology, quantum computing technology, and all manner of other technological advances will make all human labor irrelevant.

Potential Employment Automation & A New Economic System

The potential employment automation of our entire labor force, i.e. the replacement of all workers with machines, is an increasingly imminent prospect that some people view with a great deal of concern. They fear obsolescence and they are suspicious of capitalist intentions.

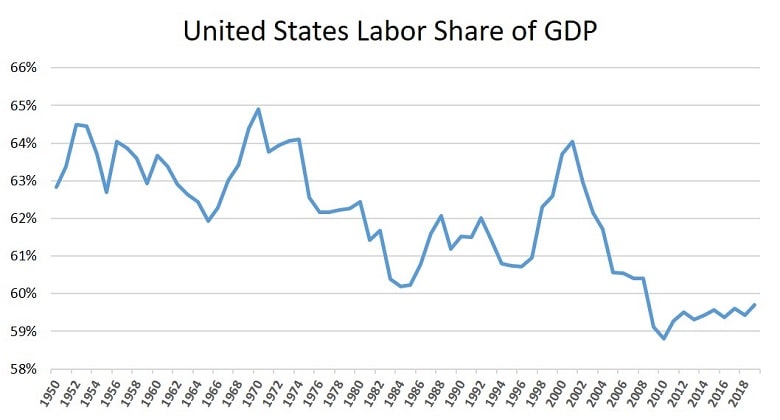

Data Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve Economic Date

Data Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve Economic DateCloser inspection should allay these fears, because there is no economic reason why it should lead to impoverishment of the masses. When humans are taken out of the production process the cost of production will essentially fall to zero (or close to it given enough time to create enough machines).

At that point the cost of providing goods and services will be close to zero, and governments will compete for votes by putting forward their plans for enabling consumers to obtain those goods and services more or less free of charge. The solution I'm referring to here is one that you will have heard of before i.e. a universal basic income, and you can skip to the section below for more details on that.

Whether or not an irrelevant, and redundant, labor force will herald a new age of prosperity or poverty will depend a great deal on how society evolves its economic system. There is, contrary to Marxist opinion, no reason to fear the changes that are coming, at least not from an economic perspective. In time we will have the opportunity to enjoy a world of plenty, without the need to work, and with all our time available for leisure and the pursuit of happiness.

Unfortunately, it is unclear if this will come with peaceful coexistence - and that is the real danger that we face. Whether people freed from the daily grind of their jobs will embrace a new life devoted to their personal relationships, to leisure, sports, the arts, literature, philosophy, learning and so on, or whether they will instead turn to their vices, to sloth, lethargy and apathy, or perhaps towards violence and conflict at the loss of meaning in their lives which their labor had previously given them.

Clearly there will be some very difficult choices to make in the years ahead, and there is no guarantee that the correct choices will be made.

Technological Unemployment Example

Resistance from workers to the introduction of labor saving technology and the resulting unemployment that it brings dates back hundreds of years. Karl Marx had even noted the 17th century workers' revolts against the ribbon-loom, and wind-driven and water-driven sawmills which had driven over thousands of people out of work. These revolts were not peaceful, and machines were routinely burned or otherwise destroyed.

Over 100,000 people were driven out of work by the first water-powered wool-shearing machine in the 18th century. By the 19th century there was a movement of English workers against new labor-saving machines in the textiles industry that had come be known as the Luddite movement. Government action against the Luddites was severe, and anyone caught destroying a machine would face the death penalty.

The Luddites did, however, have legitimate concerns. There's no doubt that progress brings massive advantages for society as a whole, but it does come at a real cost to the workers who are displaced by machines. In modern times we do have a social security safety net that workers can fall back on, but as explained in my article about the long-term effects of unemployment, that safety net can work to perpetuate worklessness.

As noted in the PDF document by Campa (see link below), in 1900 41% of the US population was employed in agriculture; by 2000 that had declined to 2%. It would be wrong to claim that the reduction had occurred solely because of the extent of automation in agriculture, because technological advances to date have always created vast numbers of alternative, better paid, jobs in other industries. However, there is no doubt that the loss of traditional jobs has caused serious losses for some people.

Some analysts, in my opinion, grossly exaggerate the costs of technological unemployment as it has so far impacted upon typical jobs. The document by Campa gives the example of a typical full-time employee earning less in 1973 than in 2014. Whilst I can't completely dissect this, it should be immediately obvious that something is amiss. Anyone who remembers the 1970s will confirm that living standards are far higher for typical workers today than in 1973. It is an absurdity to even suggest otherwise.

Causes of Technological Unemployment

The causes of technological unemployment are clear and self-explanatory, i.e. advances in technology make machines relatively more productive and cost effective than their human counterparts and therefore they are increasingly adopted in place of human labor. It is less obvious whether or not this causes overall unemployment, because whilst some jobs are lost others are created.

In previous years the overall impact has been to benefit the labor force - try getting a job as a computer programmer in the 19th century!

Going forward it appears likely that the abilities of machines that make use of advanced robotics, artificial intelligence, quantum computing technology and so on will not only replace mundane low-skilled repetitive jobs, but much more complex jobs too.

As stated at the outset, ultimately all human labor will be redundant, but there is one particular institution that is speeding up the process, i.e. the government. It does this via its policies on:

- Taxation - At present our employers are taxed very heavily for each person that they employ, but there is no parallel charge levied upon them for using a machine instead of a worker. To add insult to injury, since capital expenses are tax deductible, firms are effectively subsidized to purchase machines in place of workers.

- Regulation - This one will cause anger from some quarters that I even dare to suggest it, but worker rights like sick-pay, paid annual leave, redundancy payments, maternity and paternity pay and so on all serve to make workers more expensive and machines more attractive.

There are, of course, many other factors at play, but these two items fall withing the direct remit of the government and could therefore be manipulated relatively easily to smooth the transition into a jobless society.

A New Solution to Technological Unemployment?

Since we can assume that we are ultimately headed towards a jobless society, we can relatively easily surmise that once we are there we will need to have some sort of universal basic income (UBI) that will allow us to purchase goods and services. We can also safely assume that by the time we reach this jobless society the productivity of machines will be so advanced that we will have the means to provide a very high economic standard of living for all.

The problems we face are twofold:

- Inequality arising in the transition phase

- Nurturing peaceful coexistence

Inequality during the transition phase will be difficult to address without creating all sorts of unintended consequences. For example, if newly redundant workers are made eligible for a UBI while other workers are not then a) it wouldn't be universal and b) if made available to all any time soon then it would be extremely expensive and difficult to afford.

One solution that might assist the transition is to make skills an even bigger priority in future. New skills for the unemployed can make new jobs viable for at least some period of time before advancing technologies once again overtake us and create new redundancies, but it would at least buy us some extra time to prepare a fair and affordable UBI.

The probable timeframe for human labor to become obsolete is very long, and there will likely always be some forms of employment for those people who want it. AI is powerful, but it is still essentially a number crunching technology that has no creativity or intuition. It may surprise some readers to know that in an age of total computer domination in games like chess, the strongest chess of all is played via a combination of humans and computers.

This is a key point - technology improvements will likely complement human labor for many years to come, rather than replace it. Many current occupations will soon be replaced, but just as many new occupations will likely be created. Any sort of jobs that require creativity, e.g. product designers, architects, fashion, film, theater production, graphics, and probably countless others that don't even exist yet, are likely to see an explosion of productivity and new job creation as technology is developed that can complement human skills.

Another option would be to complement new skills with reduced working hours such that all workers could gradually reduce their workloads rather than some people losing all of their work whilst others retain all of it. This will be difficult to achieve if the most resilient types of jobs are the most highly skilled, as seems likely. For example, it would be difficult for a newly redundant factory worker to gain the skills necessary to do some part-time work as a lawyer or a doctor. Clearly this option has limited applicability, but there may be some instances of transferable skills that could be utilized this way.

If a way can be found to tackle the inequality issues that will arise as the number of displaced workers grows, then it will go a long way towards helping to alleviate any potential social unrest problems. Nurturing peaceful coexistence will become the big issue for future generations in a jobless society, and finding an alternative, rewarding and constructive activity that people can engage in to give meaning to their lives will be the key to success.

Sources:

- R. Campa - Technological Unemployment: A brief history of an idea

- Y. O Lima Et al. - Understanding Technological Unemployment

- Labor Share of GDP - St. Louis Federal Reserve Economic Data

Related Pages: