- Home

- Banking

The Fractional Reserve Banking System Explained

You may have heard the term ‘fractional reserve banking’ before without ever having given it much thought. It isn't often regarded as being an issue that a society should have much of an opinion about one way or another. But what if, combined with a central banking system that controls interest rates, it just so happens to be the single biggest cause of instability in our economies?

In actual fact, a fractional reserve banking system has the power to create such huge amounts of credit and loans, more or less out of thin air, that the resulting extra spending constitutes the primary reason for the perpetual boom & bust business cycle that we have experienced in recent decades.

In this article I will explain the destabilizing nature of the current banking system. It is not possible to pinpoint the root cause of its development, but a pivotal moment came in 1971 when President Richard Nixon suspended the US dollar’s convertibility into gold at its internationally agreed rate of $35 per ounce.

The consequences of that decision, with regard to its influence on the global money supply, has had huge repercussions right up to the present day. From the information given in this article you will begin to appreciate that something will have to change eventually, because we cannot go on forever moving in the direction that we are currently headed, it is simply unsustainable.

The alternative is a full reserve banking system, and it completely negates the excessive credit creation abilities of the fractional reserve banking system. It is an alternative monetary system that has been supported by many of our greatest economists at one time or another, and especially by the late great Irving Fisher.

Fractional Reserve Banking Effects on the Domestic Economy

Opinions diverge among economists as to the whether or not the benefits of the fractional reserve banking system outweigh the costs, but there is little doubt that the main consequences for the economy relate to its implications for short term money-supply expansion via credit creation.

The fractional reserve system has a major flaw in terms of divorcing the supply and demand for credit from the price at which it is available. As with any other market for any other product, credit has a price. That price is the interest rate payable on credit, and the consequence of being able to create credit in abundance means that interest rates are typically lower than they would otherwise be.

This is especially the case when the system is anchored to a central bank base rate of interest i.e., the ‘Fed Funds Rate’ in the US or the ‘Bank Rate’ in the UK. Central Banks are not quite so independent as it is often claimed they are. In truth they are heavily influenced by politics and the political incentive to keep interest rates low.

So, the main effect is on the credit market, and whilst it may seem like a good thing to be able to borrow money at a cheap rate of interest, the news is not so good for lenders who have little incentive to save money. The artificially cheap price of credit has the effect of subsidizing borrowing today (primarily by governments and regular people) in order to increase consumption today. However, it comes at the cost of a reduced saving rate, and a reduced amount of consumption in future.

In an aging society with a looming pensions crisis, this might not be the best idea.

One serious side-effect of pushing for more consumption right now, rather than saving, is that a sizable proportion of the extra consumption goes towards purchasing foreign imports. In the long-run this is another unsustainable trend that will need to turn around. Domestic consumption of foreign imports far exceeds foreign consumption of our exports, and the implication of that is that we are living beyond our means.

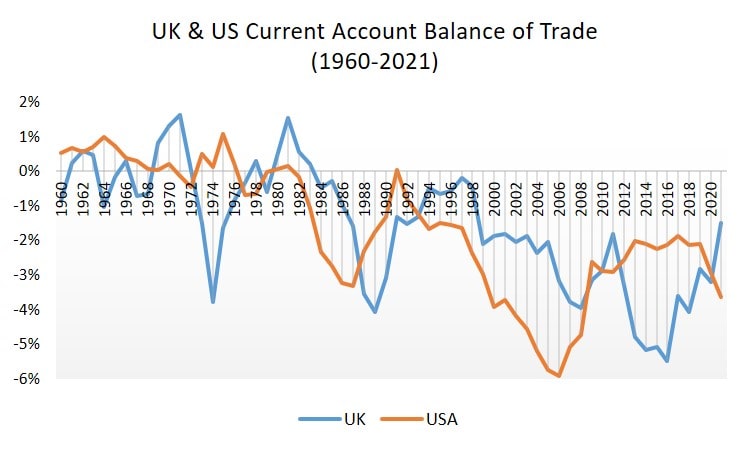

The graph below shows how the UK and US trade balances have moved sharply into deficit territory since the 1980s.

Milton Friedman has argued that there is no problem with a trade deficit, because ultimately it can only lead to depreciating domestic currency that will eventually price-out imports and boost exports, but this is one issue on which I cannot agree with him. Friedman argues that, without a market correcting depreciation, the excess money that foreigners are making must ends up being reinvested back into our economies, and he is right.

The problem is that those investments then earn a profit for foreigners, a profit that can be used to pay for a permanent stream of our goods being sent overseas i.e., the temporary surplus consumption of imported products that we now enjoy from our profligate spending habits will ultimately need to be paid for by a permanent flow of exported products being sent in the opposite direction.

There is actually an entry on the capital account of the Balance of Payments that measures the net value of domestic investments held overseas. Since the 1980s this has nosedived deep into negative territory in both the UK and the USA, meaning that foreign investors have a substantially bigger investments in our economies than we have in theirs.

Japan and Germany, traditionally the two strongest manufacturing (exporting) countries in the developed world, are notable exceptions. They have tended to have huge net surpluses of foreign investments, and both Japan and Germany have a strong historical preference for a relatively high level of saving. In the developing world, China is a massive net owner of foreign assets, and has a very strong saving rate and a much more reserved consumption rate.

A serious question arises from this as to the sustainability of those western currency exchange rates that are experiencing persistent trade deficits. They have, for too long, been offset by excessive borrowing on the capital account of the Balance of Payments. Our governments are they key culprits and have racked up so much national debt that our foreign creditors may well lose confidence in our ability to repay. If it reaches that point, there will be a currency crisis that could destroy the global monetary system.

Is Fractional Reserve Banking Fraudulent?

One of the fractional reserve banking system's biggest critics, the renowned Austrian economist Murray Rothbard, has made credible claims that the banks are actually committing fraud. The reason for this claim is that the banks, when taking receipt of our cash deposits, make a promise to return our money to us immediately upon demand.

However, in a fractional reserve banking system, the banks know that only a very small fraction of their money-deposits is needed to be kept ready for withdrawals at any given time, meaning that they lend out the rest. This in turn means that if enough of the bank's depositors presented themselves at any given moment to demand their money back, the banks would not be able to comply.

In effect, the banks are promising us something that they cannot deliver, or at least not in certain situations where demand for withdrawals of money is unusually large. This is precisely how banks fail... or how they get government bailouts at the taxpayer's expense!

The counterclaim has been made by some economists that this is not fraud because everyone knows how the system works, and they willingly partake. It seems to me that this counterclaim amounts to a declaration that it is okay for the banks to lie to us because we know that they are lying - which I find wholly unsatisfactory to say the least. It's also a false counterclaim, because some people absolutely do not know that the banks are making promises that they cannot always keep.

Sources:

Related Pages: