- Home

- Consumer Behavior

- Consumer Surplus

How to Find Consumer Surplus on a Graph (Step-by-Step)

Consumer surplus shows the extra benefit consumers get when they pay less than what they are willing to pay. In this article, I will show you step-by-step how to find consumer surplus on a graph, calculate it with the formula, and apply it to practical market examples. By the end, you’ll be able to analyze consumer surplus like an economist.

The concept of consumer surplus was first developed by the French economist Jules Dupuit in 1844 as part of his work on understanding the utility of public works, such as bridges and roads. He described it as the excess satisfaction (or utility) that consumers receive when they pay less for a good than they would be willing to pay.

The theory was later refined and popularized by Alfred Marshall, a British economist, in his book Principles of Economics (1890). Marshall formalized the concept and illustrated it using the demand curve. He is credited with providing the consumer surplus graph that is widely used in economic analysis today.

Consumer surplus arises in a market because each individual consumer has a different value that they place on the products that they purchase, and sellers are usually unable to discern that value meaning that they tend to charge the same price to all customers. Those customers who value a product greater than its price are in effect getting some surplus value for free. So, consumer surplus is equal to the difference between the price that a consumer is willing to pay for a product, and the amount that is actually paid.

Key Points:

- Willingness to Pay: This is the highest price a consumer is prepared to pay for a good or service.

- Market Price: This is the actual price the consumer pays in the market.

- Individual Consumer Surplus = Willingness to Pay − Market Price

This concept can be visualized on a graph, which makes it easier to calculate total consumer surplus for a market.

How to Find Consumer Surplus on a Graph (Step-by-Step)

Visualizing consumer surplus on a graph makes it easy to see the extra value that buyers gain. Let’s go through it step by step.

By presenting a market demand curve we can visually illustrate consumer surplus on a graph, because consumer surplus is simply the difference between the maximum price that a consumer is willing to pay for a product, and the price that he/she actually pays for it.

We know that different consumers have different preferences for different goods, and that they value these goods differently. For example, one person may have a greater need to travel from one place to another and therefore be willing to pay a much higher price for a flight there than another person.

If airlines are unable to distinguish which consumers are willing to pay higher prices, they will be unable to price discriminate i.e. they will not be able to charge one person more than another and will have to charge an equal price to all customers. The implication is that some customers will be getting surplus value from the flight because they are able to pay less for it than they would be willing to pay.

Consumer surplus shown as the area between willingness to pay and market price.

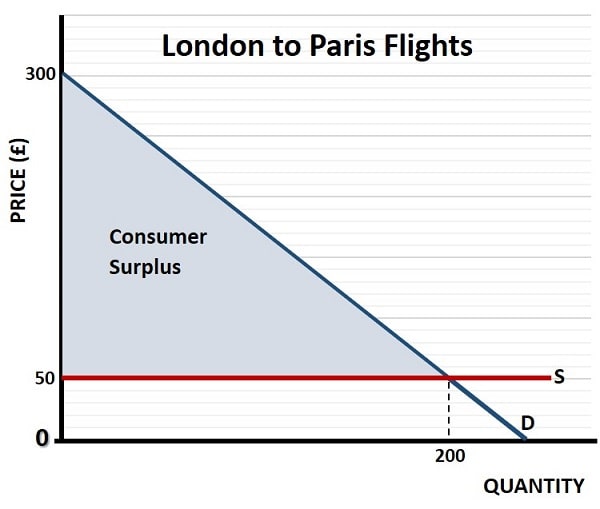

Consumer surplus shown as the area between willingness to pay and market price.In the graph above, by way of example, we can see a market demand curve for flights from London to Paris. We assume, for simplicity, that the market for flights from London to Paris is competitive and that each airline operator is a price taker. Each operator sets its airfare at the going rate of £50 as illustrated by that horizontal supply curve in the graph.

The demand curve for this market is, as with all normal goods, downward sloping. Again, for simplicity, we use a linear demand curve to illustrate the equilibrium price and quantity of flights from London to Paris at a given time and date. This occurs at the market price of £50 and a quantity of 200 consumers.

Note that the demand curve intercepts the vertical axis at a price of £300, indicating that there is no demand for flights at this price, but that at prices just below £300 there are some customers willing to pay this amount. As prices are reduced, more and more people are prepared to pay for the flight.

The area above the horizontal supply curve and below the downward sloping demand curve represents the total consumer surplus that is gained, as this equals all the extra money that could have been charged to all the customers who valued the flight at more than the £50 that they actually paid.

How to calculate consumer surplus on a graph with a price ceiling or floor

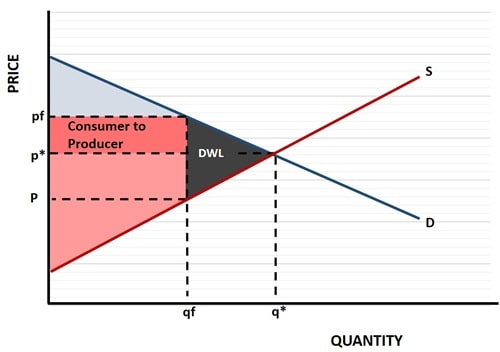

Using the graph below, we can see how a price floor set above the market equilibrium reduces consumer surplus. Step by step, you can calculate the lost value by measuring the area between the demand curve and the new market price.

In this example, the blue area is clearly smaller compared to what would exist at the market price p*. The new price is higher at pf and consumers bear the extra cost while producers gain (as illustrated by the dark red area). For details on this, see my article about Producer Surplus.

Consumer Surplus is reduced after a price floor is imposed on the market, but producers benefit.

Consumer Surplus is reduced after a price floor is imposed on the market, but producers benefit.Consumer surplus is affected by any artificial prices that may be imposed on a market. The obvious example comes by way of government-imposed price controls. In such circumstances (assuming that a price ceiling is set below the market rate, and that a price floor is set above the market rate) there will be a deadweight loss to society (illustrated by the dark gray area in the graph above) meaning that some surplus is lost to both consumers and producers depending on market elasticities.

For full details on how consumer surplus (and producer surplus) is affected by price floors and ceilings, have a look at my articles about:

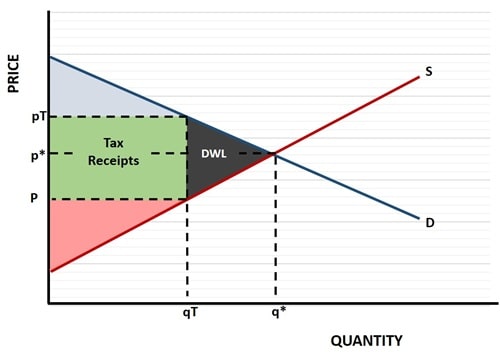

Calculating Consumer Surplus with a Tax

If a per-unit sales tax, or excise tax, is imposed on a market, it will affect it in a similar way to imposing a price floor at a rate higher than the market rate – it will lead to a situation of excess supply. The only difference is that the government gains some surplus via tax receipts that would have gone to consumers and producers. A similar deadweight loss arises as before with the price floor.

I illustrate this in the graph below:

Consumer Surplus is reduced after a tax is imposed on the market, but Government gains tax receipts.

Consumer Surplus is reduced after a tax is imposed on the market, but Government gains tax receipts.I assume here that there are no externalities at play in the market, because the presence of external factors like pollution can actually lead to overall benefits when taxes are imposed. See my article about socially optimal quantity for details on that.

An ad-valorem tax like VAT works in a similar way to a per unit tax, but in this case the tax paid increases in proportion to different market prices.

Consumer Surplus in a Monopoly Market

Consumer surplus in a monopoly raises the possibility of price discrimination i.e., the ability to charge some consumers more than others in order to capture their surplus. This may or may not be legal, often it is prohibited, but it does exist in some markets.

The more usual practice in monopoly industries is to reduce the overall supply in the market in order to charge a higher price to all consumers who remain willing to pay. This occurs because it is often more profitable to charge a higher price to a smaller number of customers than a lower price to a larger number of customers.

This practice does lead to some overall deadweight loss, but there are also some circumstances whereby a product can only be supplied by a monopolist, because only a monopolist can make enough money to cover costs of production. This is explained in more detail in my article about monopolistic competition.

Consumer Surplus Formula

There is no specific consumer surplus formula that applies in all cases because it is a function of the particular demand curve that applies in the market under scrutiny.

For a linear demand curve the formula is easy, and just requires some basic use of Pythagoras’ theorem (i.e. the area of a triangle):

Consumer Surplus = ½ x (willingness to pay – market price) x quantity purchased

For non-linear curves things get a little more complicated, and require some use of basic calculus to calculate the area under the demand curve that is above the market price. The mathematics for working out this sort of stuff is taught to 1st year undergraduates, but I won’t get into that here as my site avoids excessive use of mathematics and just focuses on the important concepts in economics.

FAQs about Consumer Surplus Theory

Can Consumer Surplus be negative?

Can Consumer Surplus be negative?

In free markets we assume that consumers act rationally and, in such circumstances, it is impossible for consumer surplus to be negative. However, not all of the products that a consumer enjoys are purchased in a free market, public goods are provided via the state. An individual consumer may be paying more in taxes for some public goods than they are worth to that individual, meaning that effective market price is greater than willingness to pay, and individual consumer surplus for those public goods is negative. If provision of a public good is particularly inefficient, the whole market for that good may experience negative consumer surplus.

Why is Consumer Surplus good?

Why is Consumer Surplus good?

Consumer surplus is considered good because it reflects the benefits and satisfaction (utility) that consumers gain from market transactions, contributing to overall economic welfare. Recall that one of the fundamental assumptions in economics is that more consumption is better than less consumption; consumers achieve their greatest level of consumption by optimizing their surplus.

How is consumer surplus used in cost-benefit analysis?

How is consumer surplus used in cost-benefit analysis?

Consumer surplus is a key metric in cost-benefit analysis to measure the benefits of a project or policy to consumers. By estimating the changes in consumer surplus, analysts can determine whether the benefits of a proposal outweigh its costs.

What role does elasticity of demand play in determining consumer

surplus?

What role does elasticity of demand play in determining consumer surplus?

The elasticity of demand affects the size of consumer surplus. When demand is inelastic, consumers are willing to pay higher prices, leading to larger surpluses. Conversely, highly elastic demand results in smaller consumer surplus because consumers are more sensitive to price changes.

How does technological innovation impact consumer surplus?

How does technological innovation impact consumer surplus?

Technological innovation often increases consumer surplus by lowering production costs, which can lead to reduced market prices. Additionally, innovation can improve product quality or introduce new goods, enhancing consumer satisfaction and surplus.

How do externalities influence consumer surplus?

How do externalities influence consumer surplus?

Positive externalities, such as public benefits from education, can enhance consumer surplus indirectly by increasing the perceived value of goods or services. Negative externalities, like pollution, may reduce consumer surplus by diminishing the overall utility derived from market transactions.

Understanding Consumer Surplus: Step-by-Step Recap

Consumer surplus highlights the benefits consumers derive from participating in the market. By paying less than their maximum willingness to pay, consumers gain utility, which contributes to overall economic welfare.

The theory, first introduced by Jules Dupuit and later refined by Alfred Marshall, is used to illustrate market dynamics, price controls, and taxation effects. While the presence of monopolies or government interventions can alter or diminish consumer surplus, its analysis offers valuable insights into resource allocation, welfare economics, and market efficiency.

By using the graphs and formula as shown in this guide, you can calculate consumer surplus in any market situation and understand the real benefits consumers receive.

Related Pages:

- Producer Surplus

- The Demand Curve

- The Linear Demand Curve

- Deadweight Loss

- Price Controls

- Marginal Utility

- Consumer Behavior

About the Author

Steve Bain is an economics writer and analyst with a BSc in Economics and experience in regional economic development for UK local government agencies. He explains economic theory and policy through clear, accessible writing informed by both academic training and real-world work.

Read Steve’s full bio

Recent Articles

-

What Happens to House Prices in a Recession?

Jan 11, 26 03:13 AM

What happens to house prices in a recession? Learn how different recessions affect housing, why 2008 was unique, and how policy responses change home values. -

Does Government Spending Cause Inflation?

Jan 10, 26 06:01 AM

Does government spending cause inflation? See how waste, crowding out, and stimulus spending quietly push prices higher over time. -

What Happens to Interest Rates During a Recession

Jan 08, 26 05:31 PM

What happens to interest rates during a recession? Explore why rates often fall, when they don’t, and how inflation, policy, and markets interact. -

Circular Flow Diagram in Economics: How Money Flows

Jan 03, 26 04:57 AM

See how money flows through the economy using the circular flow diagram, and how spending, saving, and policy shape real economic outcomes. -

What Happens to House Prices During Stagflation?

Jan 02, 26 09:39 AM

Discover how house prices and real estate behave during stagflation, with historical examples and key factors shaping the housing market.