Income

Elasticity of Demand (YED) Explained, with a Graph

Income Elasticity of Demand is defined as the responsiveness of the quantity demanded of a good, by consumers, to changes in consumer income. In other words, it measures whether consumers buy more or less of a good when their disposable incomes rise, and by how much.

Once gathered, this is useful information for businesses, governments, and economists, because it helps to build up an understanding of consumer behavior and market dynamics:

- Businesses – Use YED for pricing and product strategy. For example, high income groups are targeted with luxury goods since these have a high YED.

- Economists & Analysts – Use YED to assess which industries will perform well during economic booms and which will remain stable or decline.

- Government Policy makers – Use YED to help construct an effective tax & welfare system. It also helps with economic growth planning in underperforming localities.

As with price elasticity of demand, income elasticity of demand falls into a number of categories depending on a calculated coefficient. I will explain this below, but let’s start with some simple graphs to illustrate the key concepts.

Income

Elasticity of Demand Graph

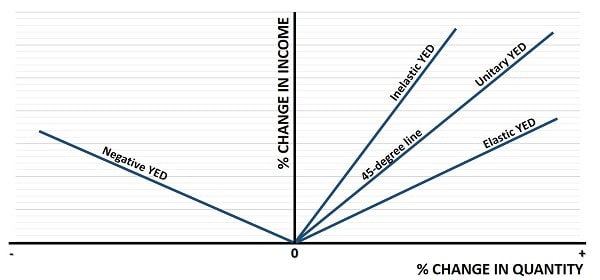

The income elasticity of demand graph illustrates the four categories that define how a positive percentage change in income affects the quantity demanded of a given product. On the left-side of the graph, an increase in income leads to a decrease in quantity demanded.

On the right-side, starting with the 45-degree line, any given percentage increase in income leads to an equal percentage increase in quantity demanded, and so YED is unitary. Steeper curves indicate inelastic YED because quantity demanded increases by a smaller percentage than any associated increase in income. By the same reasoning, curves less steep than the 45-degree line indicate elastic demand.

The Four YED

Categories

- YED < 0 (Negative YED). Inferior goods have a negative income elasticity of demand, meaning that demand decreases as income increases. Examples include Instant noodles, public transportation, second-hand clothing etc. This is because consumers tend to switch to higher-quality alternatives when their incomes increase.

- 0 < YED < 1 (Inelastic YED). Normal goods for which demand increases with income, but at a slower rate. Examples include household appliances, electricity, dental care etc. These are often essential goods, so even if income rises, consumption does not increase drastically.

- YED = 1 (Unitary YED). This is more of a theoretical possibility that is included here to complete all possibilities. There may be some narrow range of products, under certain circumstances, for which there is unitary income elasticity of demand, but it is not common.

- YED > 1 (Elastic YED). Luxury Goods for which demand increases more than proportionally as income rises. Examples include Designer clothing, fine dining, high-end electronics, luxury cars etc. These goods are not essential, but they are desirable, and people buy them more when they have extra income.

I should note here that these categories will be different for different people. What is a luxury good with highly elastic YED for one consumer may be regarded as an inferior good for another consumer. I’m not referring to differences in tastes here, I’m referring to the impact that different levels of disposable income have on preferences.

For example, poorer consumers may regard a fast-food restaurant meal as a luxury good, but for richer consumers this type of food may be considered an inferior good.

Income

Elasticity of Demand Formula

How to Work

Out Income Elasticity of Demand

To restate what I have written above, the income elasticity of demand measures the percentage change in quantity demanded of a good, divided by a percentage change in disposable income. This is usually written as:

YED = %ΔQ / %ΔY

Solving this equation is a simple matter if we can gather the necessary data. If a consumer wishes to assess his/her own spending then all the data is readily available, but it does become a much more arduous task to gather data for an entire industry with respect to individual goods and services.

This difficulty is compounded by the fact that there are usually many other forces at work in an economy than income levels alone, that affect purchasing decisions. Regardless of the difficulties, economic agents do conduct these sorts of studies for the reasons given in the opening section above.

The YED

Coefficient

The YED coefficient is the single number that we arrive at after running the data through the formula above. While it will usually be a number that is not too distant from 1, there is no upper or lower limit. For a description of what the numbers indicate, see the YED categories above.

Income

Elasticity of Demand Example

By way of example, let’s suppose that your monthly disposable income increases from $2000 to $3000 and that, as a result of this, you decide to increase your spending on restaurant dining from $100 per month to $300 per month, which allows you to increase your quantity of restaurants dinners from 2 per month to 6 per month.

We can calculate income elasticity of demand using the formula YED = %ΔQ / %ΔY

YED = ((6/2) / (1,000/2,000)) = 6

So, the YED coefficient here is 6, meaning that restaurant dinners are a luxury good for you. You chose to spend a disproportionately larger amount of money on restaurant dinners given your increased income.

YED and

Economic Growth

Every economy consists of three sectors: primary (agriculture, forestry, fishing, extraction), manufacturing, and services (banking, healthcare, education, etc.). As economies grow, the relative size of these sectors shifts due to income elasticity of demand.

- Primary sector goods (e.g., food, cotton, rubber) have low YED (inelastic), meaning demand grows slower than income. Some, like cotton and rubber, also face competition from synthetic substitutes.

- Manufactured goods (e.g., cars, computers) usually have high YED (elastic), so demand grows faster than income.

- Services (e.g., education, healthcare, travel) tend to have an even higher YED, leading to rapid expansion as incomes rise.

Over time, developing economies transition from predominantly agriculture to manufacturing, and then to services, with the latter dominating in fully developed nations. Less developed economies still rely heavily on the primary sector, while advanced economies see rapid growth in service industries like finance, healthcare, and education.

FAQs about

Income Elasticity of Demand

How does technological advancement affect the Income

Elasticity of Demand for certain goods?

How does technological advancement affect the Income Elasticity of Demand for certain goods?

Technological advancements can lower production costs and increase affordability, shifting a good from being a luxury (high YED) to a normal good (moderate YED). For example, smartphones were once luxury goods but have become more inelastic due to widespread adoption and affordability.

How does consumer perception affect the classification of a

good as luxury, normal, or inferior?

How does consumer perception affect the classification of a good as luxury, normal, or inferior?

Consumer perception is crucial—branding and marketing can make a normal good appear as a luxury item. For example, bottled water is functionally a necessity, but premium brands market it as a luxury product, increasing its YED.

How does YED influence business expansion strategies in

different economies?

How does YED influence business expansion strategies in different economies?

Companies analyze YED when deciding where to expand. High YED goods perform well in growing economies with rising incomes, while businesses selling low YED or inferior goods may find stable demand in low-income markets.

How does YED interact with brand loyalty and consumer

habits?

How does YED interact with brand loyalty and consumer habits?

High brand loyalty can reduce the impact of YED. Consumers with strong brand attachment may continue purchasing a luxury brand even if their income drops, making the product appear less elastic than it would otherwise be.

What happens when a company miscalculates the YED of its

product?

What happens when a company miscalculates the YED of its product?

Misjudging YED can lead to poor pricing strategies. If a company assumes a product has high YED but demand remains stagnant despite income growth, they may overproduce, resulting in excess inventory and losses.

Associated

Elasticities

- Price Elasticity of Demand (PED) measures how the demand for a good changes as its price changes. Goods with high YED i.e., luxury goods, often also have high PED because consumers can delay purchases if prices rise.

- Cross Price Elasticity of Demand (XED) measures how the demand for one good changes due to the price change of another good i.e., a substitute or complement. A good with high YED may have strong positive XED with complementary luxury goods.

- Price Elasticity of Supply (PES) measures how much supply responds to price changes. Luxury goods with high YED often have low PES because production takes time (e.g., handmade watches).

Conclusion

Income Elasticity of Demand is a basic tool for understanding market demand and economic behavior. It influences business pricing strategies, production decisions, and government policies.

By analyzing YED alongside other elasticity measures, businesses, economists, and government policy makers can make better decisions about product positioning, market trends, and social programs.

Related Pages:

About the Author

Steve Bain is an economics writer and analyst with a BSc in Economics and experience in regional economic development for UK local government agencies. He explains economic theory and policy through clear, accessible writing informed by both academic training and real-world work.

Read Steve’s full bio

Recent Articles

-

U.S. Industrial Policy & The Unfortunate Sacrifice that Must be Made

Dec 12, 25 03:03 AM

U.S. Industrial Policy now demands a costly tradeoff, forcing America to rebuild its industry while sacrificing bond values, pensions, and the cost of living. -

The Global Currency Reset and the End of Monetary Illusion

Dec 07, 25 03:48 AM

The global currency reset is coming. Learn why debt, inflation, and history’s warnings point to a looming transformation of the world’s financial system. -

Energy Economics and the Slow Unraveling of the Modern West

Dec 06, 25 05:18 AM

Energy economics is reshaping global power as the West faces decline. Explore how energy, geopolitics, and resource realities drive the unfolding crisis. -

Our Awful Managed Economy; is Capitalism Dead in the U.S.?

Dec 05, 25 07:07 AM

An Austrian analysis of America’s managed economy, EB Tucker’s warning, and how decades of intervention have left fragile bubbles poised for a severe reckoning. -

The Looming Global Debt Crisis – According to Matthew Piepenburg

Dec 04, 25 02:38 PM

A deep analysis of the unfolding global debt crisis, rising systemic risks, and the coming reckoning for bonds, stocks, real estate, and the dollar.