- Home

- Business Cycle

What is the

Business Cycle in Economics? (Causes & Solutions)

The business cycle, also called the economic cycle, is a phenomenon that describes the way in which the actual level of output grows in phases that deviate around a long-run trend growth rate. In other words, the national income does not grow at a steady rate, there are periods of rapid growth and periods of negative growth (recession) around that trend rate.

The unstable rate of growth can actually cause serious problems for many people, particularly the recession periods that can cause loss of jobs and income, and there is even the possibility that instability might actually cause a somewhat reduced long-run trend growth rate.

There is actually a great deal of controversy surrounding the causes of, and solutions to, the business cycle. In essence it has led to the biggest divide in economics i.e., the debate between short-term demand management Keynesian economists, and the laissez-faire long-term focused classical school of economics.

Opinion is further divided amongst Monetarist and Austrian economists, so it goes without saying that the theory here is somewhat less than settled! Nevertheless, after a quick explanation of the business cycle, I will offer my own thoughts and opinions about the key drivers of economic output fluctuations, along with some important historical examples.

Business

Cycle Graph

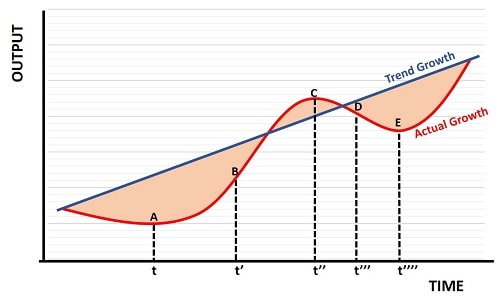

The business cycle graph below shows total economic output (a measure of national income) on the vertical axis, and the passage of time on the horizontal axis. The linear blue line represents the long-term growth rate of the economy; it is upward sloping, illustrating that, as time passes, there tends to be a sustainable increase in the level of economic output.

That sustainable growth rate will change somewhat over time for many reasons, with the rate of technological improvement, structural reasons, and demographic changes, being the most important.

I should point out here that not all countries enjoy sustained economic growth, there are many examples of subsistence economies in the present day that still exhibit little to no improvement in the economic standard of living. However, most economies do manage to consistently grow once the basic free-market institutions are in place e.g., the rule of law, trust in the enforcement of that law, property rights, and individual freedoms.

In the business cycle graph I have also illustrated, in red, the actual economic cycle that is typical of real-world experiences in most countries. Along the fluctuating red line, there are four distinct stages of the business cycle. Points A through to E mark these phases.

What are the

4 Stages of the Business Cycle?

Starting at point A in the graph, the economy is in a slump, with economic output way below trend. Point B marks a rapid period of recovery, point C indicates a boom with output exceeding its sustainable level, point D illustrates a period of recession and probably growth in cyclical unemployment, and point E takes us back to the beginning of another business cycle. The typical cycle has lasted around 7-12 years in recent history, but there is no reason why shorter or longer cycles can’t happen.

Business

Cycle Phases

- Slump – An economic slump marks the low-point in the business cycle, with output well below potential productive capacity.

- Recovery – The recovery phase of the cycle occurs as the economy realigns productive resources into profitable ventures.

- Boom – An economic boom occurs as overconfident businesses and consumers increase spending faster than output can increase.

- Recession – With spending outpacing production, prices hit a peak causing demand to fall off, which then causes output to decline.

Controversies

in Business Cycle Theory

The Austrian Business Cycle Theory argues that it is the lack of free-market price discovery in the most important market of all i.e., that for money, that causes malinvestment in business ventures. and eventual business failures and output drops. The key here is that it is the interest rate that is manipulated by central banks that is to blame, and that if the free-market were allowed to determine the interest rate then there would be no business cycle.

I am a fan of the Austrian school, and years of previous experience working for the public sector has opened my eyes to the incompetence of central planners.

Central Banks have an almost unblemished record of failure when it comes to setting an appropriate interest rate. It leads to reckless overspending on the one hand, when interest rates have been too low, followed by unserviceable debt on the other hand when interest rates have to rise. This has certainly been a key factor in recent business cycles.

Real Business Cycle Theory suggests that fluctuations in the actual growth rate do not represent deviations from the long-run growth rate at all. Rather, these fluctuations are a form of correction. The idea is that, when output falls, it is because there had previously been an overestimation of future sustainable growth, and when that overestimate is realized there is a natural downward readjustment in economic output.

The point here is that, if the theory is correct, there are no underutilized resources in the economy that could be put to work via discretionary fiscal or monetary policy. If correct then this would make Keynesian demand-management policies counter-productive.

Monetarist Theory focuses on the impact of the money-supply on the business cycle. They argue that, if interest rates are set too low, the money-supply will expand via excessive bank-lending, and the resulting increase in spending will cause the economy to overheat with unsustainable growth. A recession is the unavoidable consequence of such growth.

Rather than prescribing interest rate control to the market (instead of incompetent central planners) to control the money-supply, the monetarists prescribe a small but constant growth in certain monetary aggregates to match economic growth. This, they argue, will be sufficient to avoid any excessive spending. Excessive economic growth and consequent recession can then be avoided.

Real-world experiments with the monetarist approach to macroeconomic management during the 1980s did not go so well. In practice the money-supply is hard to control directly, and all attempts to control monetary targets failed miserably.

Classical Economists take a hands-off approach to management of the economy and argue that, while the business cycle does exist, the short-term fluctuations in output are not long lasting and will soon be corrected without need for intervention in the marketplace. They believe that all prices are flexible, even wages, and if unemployment were to arise during a recession, then workers would quickly accept lower wage rates to gain employment.

Furthermore, these economists argue that it is more often the case that any sort of intervention in the economy is more likely to exacerbate the boom-bust cycle rather than correct it. This is because of all the problems associated with lag-effects in countercyclical policy.

Keynesian business cycle theory puts the blame for output fluctuations on volatile levels of investment. Business investment in particular is argued to be quite sensitive to confidence levels related to the projected future profitability of business ventures. If confidence falls for whatever reason, investment funds could quickly dry up and economic output would then fall. Related to this is the net exports effect, which could explain output fluctuations occurring as a result of falling foreign demand for domestically produced goods.

In response to this, Keynesians advocate a strong role for discretionary fiscal policy to counteract any fall in investment levels. This, it is argued, can smooth out the economic growth path and restore business confidence and investment levels.

Empirical evidence of investment falls driving falls in output are strong, but it is much more correlated with consumer investment in housing than it is in business investment. My article about investment spending delves into this.

Business

Cycle Examples

The Great

Depression

The Great Depression of the 1930s had its origins in the excessive credit fueled spending of the roaring 20s. The Federal Reserve had been created in 1913 after a spate of bank failures that threatened confidence in the entire banking system. The system up to this point was made up of thousands of small private banks, and anyone who had money deposited in them stood to lose it in the event of a bank failure.

The Federal Reserve Act was introduced to bring confidence back to the system, but it handed control of interest rates to the central planners.

True to form, the central planners immediately set about getting things wrong, and by the late 1920s the artificially low interest rates of the time had created a massive stock market bubble. When that bubble burst it led to widespread financial panic, and a rush to get money out of the banks.

The bank runs led to more bank failures than ever before, and many of them failed. There was no bank deposit insurance scheme at the time, so many people lost all of their money. The resulting business cycle explosion created a huge recession, with unemployment peaking at almost 25%.

The chaos that ensued led to the formation of Keynesian economics, with the argument that if only the government had stepped in with massive fiscal stimulus, then much of the damage could have been avoided. The classical and free-market advocates, on the other hand, argued that if the free-market had been setting interest rates rather than the central planners, then the financial bubble that created the problem wouldn’t have arisen in the first place.

The 1970s

Stagflation

The business cycle of the 1970s was a real eye opener for the Keynesians (who had come to dominate economic policy by this time). Up until the 1970s there had been complete confidence in the Phillips curve tradeoff between unemployment and inflation, but the 1970s changed all that.

The economy experienced both high unemployment and rising inflation concurrently, a phenomenon that came to be called stagflation.

While the Keynesians resorted to their typical policy of boosting demand by spending more money to stimulate the economy out of recession, this only added fuel to the inflation fire. This whole episode is a good example of the real business cycle theory winning through. It wasn’t, in fact, a business cycle but an external economic shock that caused a genuine fall in economic output capacity. Rising oil prices, and geopolitical events, had led to a contraction in the supply-side of the economy that no stimulus package could correct.

The Great

Recession

The great recession refers to the period following the 2008 financial crisis when, once again, the banking system came under severe pressure after a long period of excessive credit creation. The run up to the crisis had seen a period of several years where low interest rates had fueled a property market bubble. When the bubble burst, property values collapsed and the banks were left with massive amounts of bad debts in the form of mortgage-backed securities.

Once again, the Fed has to take the blame for creating the bubble, because the free-market would surely have demanded much higher interest rates well before the housing market bubble emerged. Additionally, the low interest rates led to the formation of lots of ‘zombie companies’ that couldn’t survive with realistic interest rates.

The Great Recession is a classic example of the Austrian Business Cycle Theory playing itself out. Unfortunately, the lessons from this have not been learned, and in 2024 it seems that we are in danger of a much deeper crisis emerging due to the truly insane levels of national debt and ‘financialization’ of the economy following almost 14 years of ZIRP (zero interest rate policy) after the 2008 crisis.

Summary of

Economic Cycles and related Controversies

As discussed, the business cycle refers to the recurring pattern of economic expansion and contraction experienced by modern economies. It consists of four phases and, while the concept is widely accepted in economics, there are several controversies surrounding it:

- Predictive Accuracy – Critics argue that accurately predicting the timing and duration of each phase of the business cycle is challenging. Economic indicators are often subject to revisions, making it difficult for policymakers and businesses to make timely and informed decisions.

- Causes of Business Cycles – Economists differ in their views on the underlying causes of business cycles. Some attribute them to external shocks, such as changes in technology or geopolitical events, while others emphasize internal factors like monetary policy, fiscal policy, or financial instability.

- Government Intervention – There is ongoing debate about the appropriate role of government intervention in managing the business cycle. Advocates for intervention argue that it can stabilize the economy, while opponents contend that it may exacerbate economic imbalances and distort free-market mechanisms.

- Financialization – The role of financial markets and institutions in influencing the business cycle has become a point of contention. Critics argue that financialization, characterized by the growing influence of financial markets on the broader economy, may contribute to more severe economic downturns.

Related Pages: