- Home

- Aggregate Demand

The Aggregate Demand Curve

Aggregate demand, as the name suggests, can be thought of as the sum of all demand for output produced at the level of an economy, and its curve plots all points at which there is a stable balance (or equilibrium) between the goods market and the money market.

On this page I will provide a thorough account of the components of aggregate demand and its functions. It's a little more in-depth than any demand curve relating to a particular product, and it pays to invest a little time on understanding it because it relates closely to many other macroeconomic models and ideas.

I've been critical of many of those related models, but the concepts here are sound and uncontroversial. Most of the controversy that arrives with other models relate to the perspectives of different schools e.g. Keynesian versus Monetarism versus Austrian, versus Neoclassical and so on.

Wherever there is controversy I try to be clear about my own opinions, and that usually entails disagreeing with Keynesian opinions, but there is no one brand of economics that I can reasonably slot into on each and every situation. There are circumstances when all of the main schools of thought have compelling arguments on their side, and others where they are less so.

I guess my point here is just that you can regard the instruction on this page as being free of bias and just a basic building block of the later models where opinions do start to diverge.

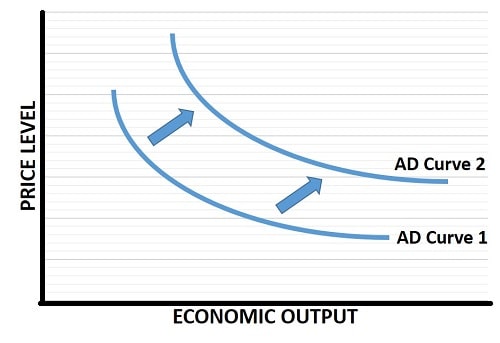

Aggregate Demand Curve Graph

The aggregate demand graph illustrates the simple trade-off that occurs in the goods and money markets between output and prices. At all points along AD Curve 1 there is equilibrium in both markets. Holding all other factors constant, a higher price level necessarily implies a reduction in potential output because there is only a limited willingness/ability to purchase goods and services, and this is reduced as the price level rises.

Of course, all other factors are rarely constant and so the aggregate demand curve can move to a different trade-off position. Those factors are many and varied and you can read about them in the section below about the components of aggregate demand.

For now, you just need to be aware that factors other than the price level will cause a shift of the whole AD curve rather than a movement to a new point along the existing curve. In the graph, this is illustrated by an expansion from AD curve 1 to AD curve 2. A contraction would move the curve in the opposite direction.

The Components of Aggregate Demand

The main components of aggregate demand include:

- The level of consumption - this is the biggest factor and simply refers to the total amount of consumer spending on goods & services from private citizens in an economy. This can vary according to the business cycle, with consumer demand being higher during boom periods and lower during slowdowns. At any given point within that cycle, consumer confidence (e.g. relating to job security) can affect the willingness of people to spend rather than save their income and wealth.

- The level of Investment - as with consumer confidence, business confidence is a major determinant of how much firms wish to spend on new investment projects. This is also clearly affected by the business cycle, but the interest rate effect on desired investment spending is also important. Foreign direct investment (i.e. foreign companies investing in the home economy) also counts.

- Government spending and taxation - commonly referred to fiscal policy, this is one of the two main policy tools that the government uses to manipulate the economic growth rate i.e. to try and prevent recessions and booms. More government spending and/or lower taxes both have the effect of boosting the aggregate demand curve.

- Foreign demand - trade with other countries is an important component and some countries have a bad trade deficit i.e. more total spending on foreign goods relative to domestic goods, but international borrowing, e.g. when foreign firms buy government bonds from the home country, also injects resources that influence demand.

This gives rise to the popular macroeconomic function:

AD = C + I + G + (X-M)

In words this means that aggregate demand equals consumption spending, plus investment spending, plus government spending, plus exports minus imports.

When the economy is in equilibrium at the intersection of demand and supply, AD also equals national income i.e. gross domestic product (GDP). This is all basic Keynesian theory, and you should keep in mind that things do get more complicated as the theory behind this function is developed, but there's no harm in introducing it to you right now.

With government spending, i.e. discretionary fiscal policy, included in the function, you might wonder about monetary policy and where it fits in:

- Changes in the money supply - commonly referred to as monetary policy. This may or may not be closely related to interest rates since money supply increases are typically associated with lower interest rates, but I've written more about this highly controversial topic on mage page about the 'IS-LM model'.

At this stage, monetary policy is not really a component of aggregate demand since it works more by influencing the other components rather than as a distinct and separate thing in itself, but whilst this is true it is also the main tool used in macroeconomic policy to influence the level of real GDP growth, so I thought I'd give it a special mention.

The general point is that the aggregate demand curve can move, and constantly does move, for many different reasons. In the context of demand-management policy, we only focus on the two tools at the government's disposal that can move the curve in a direction deemed desirable i.e. fiscal policy and monetary policy.

Demand Functions & Keynesian Demand Management of Spending

The components of aggregate demand for any economy are vast and varied, and in constant flux, but for analysis purposes this doesn't really present a problem since all these different determinants tend to cancel each other out for any narrow time period.

What matters more from an economic analysis point of view is the understanding of how deliberate expansionary (or contractionary) economic policies influence total demand and GDP. Government tax and spend policies are one form of policy tool to manipulate real output, but monetary policy is the main tool in an international system with floating exchange rates.

Now, I've mentioned that this page lacks controversy and just details accepted mainstream economic opinion. This is true but I should point out that the theory is underpinned by the IS-LM model, and this is not so readily accepted. I think the inconsistency is not so great, and that disagreement with the IS-LM model alone does not cast the general observations of the AD curve into question - only the finer workings of interest rates and their relationship to the money supply in particular circumstances. Those circumstances are not presented here, and need not concern the general ideas behind the aggregate demand curve or its functions.

Demand Side Business Cycles

The key to the model and its use in policy formulation to promote economic stability lies in its focus on manipulating the money supply to avoid recession whilst maintaining a given level of price inflation within acceptable bounds. In reality the government does not really target the money supply directly, but rather the interest rate - it then allows the money supply to settle at a level consistent with the preferred interest rate.

The point is to control the price level in order to prevent inflation, because too much inflation would imply that the economy is over-heating and that GDP growth needs to slow down.

Interest rates are strongly related to the rate of inflation, in normal circumstances, via the Fisher equation. This simple equation states that 'real' interest rates must equal price inflation plus a risk premium. For example, lenders will not loan money in receipt for an interest rate that lower than the inflation rate since the repayments they received would have less purchasing power than the money they lent. Clearly lenders need to charge a rate that is sufficient to cover inflation, as well as a premium that covers risk and thereby earns a stable and profitable rate of return.

So, in normal circumstances the manipulation of interest rates by government will lead to shifts in the money supply, and then aggregate demand shifts. The level of economic output i.e. GDP, will then be prevented from growing too quickly and causing price level increases that lead to inflation. This is the key purpose of Keynesian demand management.

I should point out that in Keynes' day the international monetary system known as Bretton Woods was in place, and this was a system of fixed exchange rates against the US dollar. The implication of fixed exchange rates is that an independent interest rate policy is not possible since interest rates influence exchange rates. However, fiscal policy, i.e. government tax and spend policies, are effective.

In times when the economy is depressed, Keynes' theory recommended more government spending and running up the national debt as a solution to promote growth of GDP. When the economy was growing too quickly, cutting spending and paying down the debt was recommended. What was never recommended, but what has become typical of modern Keynesian economic policy, is to push for more and more spending regardless of circumstances and regardless of the debt level.

Keynes developed his model as a response to the business cycle. He had observed that a large fall in GDP is usually caused by an aggregate demand shock. Keynes believed that the aggregate supply curve was more or less fixed, and that cyclical unemployment resulting from booms and recessions could be controlled simply by maintaining a stable level of aggregate demand.

This remains one of the foundations of mainstream economic theory to this day, but we now know that there are occasions when the short run aggregate supply curve can also shift significantly. The classic example of this relates to the 1970s and the impact of oil price rises at that time. When recessions are caused by supply shifts rather than demand shifts, expansionary Keynesian demand management is not the best policy response because it puts huge pressure on inflation. In these circumstances is it better to tolerate falls in GDP.

Criticisms for further study

The most frequently heard criticisms of the theory behind the aggregate demand function relate to the policy recommendations that flow from it. Keep in mind that this is the foundation of Keynesian economics, but that there are alternative schools of thought within the science that are worthy of serious study.

The most popular of criticisms of aggregate demand based policy are based on its interaction with aggregate supply, and I'd encourage you to have a look at my page about that via the link at the bottom of the page.

For now, the main bone of contention comes down to whether or not the government can boost total output and GDP without causing an increase in the price level. Keynesians argue that, in times of recession, this can indeed be done. Classical and Monetarist economists often disagree with this assessment, and therefore draw different recommendations for government policy.

They do not, however, have any fundamental objection to the manipulation of the aggregate demand curve to drive GDP in whichever direction is deemed desirable. This sets their criticisms apart from those of the Austrian school.

The Austrian school argues that manipulations of this sort cause huge economic damage which will decrease long term GDP potential via distortions to the price mechanism at the level of the micro-economy.

Boosting aggregate demand will cause some goods to artificially increase in price more than other goods, and this in turns will cause new business investment to reflect these new artificial prices. The Austrians further argue that fiscal and monetary policy actions cause distortions to the 'natural rate of interest', and that the result of all this macro-level manipulation is severe malinvestment - which is the cause of the GDP boom-bust cycle rather than the cure.

Sources:

Related Pages:

- Aggregate Supply

- The AD-AS Model

- Natural Rate of Unemployment

- Keynesian Consumption Function

- The IS-LM Model

- Crowding Out

- Investment Spending

- The Aggregate Expenditure Model

About the Author

Steve Bain is an economics writer and analyst with a BSc in Economics and experience in regional economic development for UK local government agencies. He explains economic theory and policy through clear, accessible writing informed by both academic training and real-world work.

Read Steve’s full bio

Recent Articles

-

Bank Reserves, Asset Inflation, and the Risk of Future Price Inflation

Dec 19, 25 04:16 AM

Learn what bank reserves are, how they affect asset prices, and why future reserve creation could lead to inflation through commodities and currencies. -

Credit Creation Theory; How Money Is Actually Created

Dec 16, 25 03:07 PM

Explore how modern banks create money through credit creation, why the money multiplier fails, and the role of central banks and reserves. -

U.S. Industrial Policy & The Unfortunate Sacrifice that Must be Made

Dec 12, 25 03:03 AM

U.S. Industrial Policy now demands a costly tradeoff, forcing America to rebuild its industry while sacrificing bond values, pensions, and the cost of living. -

The Global Currency Reset and the End of Monetary Illusion

Dec 07, 25 03:48 AM

The global currency reset is coming. Learn why debt, inflation, and history’s warnings point to a looming transformation of the world’s financial system. -

Energy Economics and the Slow Unraveling of the Modern West

Dec 06, 25 05:18 AM

Energy economics is reshaping global power as the West faces decline. Explore how energy, geopolitics, and resource realities drive the unfolding crisis.