- Home

- Inflation

What is Inflation, and why is it Bad?

Most people think that inflation means a rise in prices, but that's not quite right. Inflation is not a one-off event, it's a process of continually rising prices that is usually measured at an annual percentage rate. It's an important distinction.

Technically, inflation was a word that was originally used to describe the state of a growing money-supply, and a rising price level for consumer goods was seen as a consequence of that growth. Some economists still conflate these two meanings, and it pays to be aware of that in order to avoid confusion.

On this website I use the word inflation in its modern sense, as relating directly to persistent rises in the general price level, regardless of the money-supply, with consequent loss of purchasing power for any given amount of currency.

A price change to reflect market forces is usually desirable, but a higher inflation rate beyond some minimal target level is always a bad thing for society as a whole. It may be that at times a little more inflation is accepted as the lesser of two evils, but it is never a good thing in and of itself.

The cost of inflation to society comes in either its destabilizing effects on the economy, or in the unfair way in which it redistributes wealth. Both of these bad effects are explained below, but first let's have a look at how the economic analysis of inflation has developed over the years.

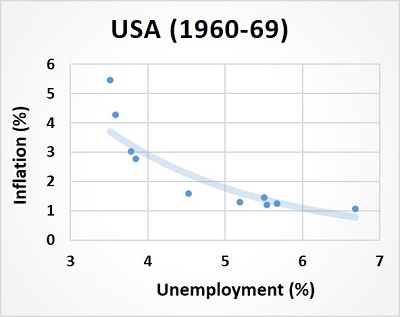

Governments in the post World War 2 period were focused primarily on reducing unemployment, and at the time it seemed that there was a tradeoff between low unemployment with higher price inflation, or vice-versa.

This tradeoff was mapped out by the Phillips Curve, as illustrated in the graph above. Successive governments would simply choose where on the curve their tradeoff preferences were optimized, and then set their economic policies to reach that point.

The idea behind the tradeoff was that, when unemployment was low, firms would experience difficulty recruiting extra workers. As a consequence of that, existing workers would have more power in the marketplace to negotiate higher wages. This would then create a kind of cost-push inflation, because firms would need to recoup the cost of those higher wages by charging higher prices for their goods and services.

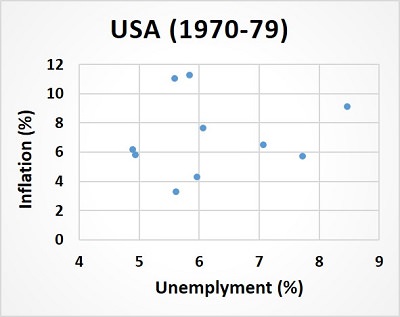

Things seemed to be working well until the 1970s when, inexplicably at the time, the relationship between the unemployment rate and the inflation rate broke down (see the graph below). Persistent high inflation occurred at that time even as unemployment numbers increased, meaning that the Phillips curve tradeoff disappeared.

The accepted wisdom of the day, that consumer price inflation was caused by cost push factors related to rising wages, had failed to explain what was happening. Economists went back to the drawing board.

It turns out that higher wage demands are not usually the cause of price inflation, they are more often a response to it.

A new theory of inflation was needed, and one was duly put forward by Milton Friedman that came to be accepted by the economics profession. In Friedman's own words:

"In order to stop inflation you have to have the government spend less and print less. That's the only way you are going to stop inflation, that's the one and only cure."

(Milton Friedman)

In other words, the money-supply in an economy is the sole determinant of price inflation. If it is increasing faster than economic output can keep up, the economy will overheat and inflation will result. Conversely, if it grows too slowly (as Friedman claimed was the case prior to the great depression of the 1930s) the economy will contract with growing unemployment and deflation (i.e. negative inflation) being the result.

These insights showed that there was no long-run tradeoff between unemployment and inflation, and that governments could seek to obtain an economy with both full employment and stable low inflation. However, to get a rising price level under control, there is no way to avoid the pain that comes with a contraction in the money-supply (a probable recession causing some unemployment during the adjustment phase).

In other words, in the short-run (which Friedman estimated to be about 2-years) the Phillips curve still exists and there is a tradeoff between price inflation and unemployment, but in the long-run this relationship disappears, with unemployment in the economy settling at its 'natural rate'.

A key breakthrough in Friedman's model was the role of 'inflation expectations' and, for full information about, that have a look at my article:

Cost Push Inflation or Demand Pull Inflation?

The debate over how inflation arises and persists is not settled. While the old theory of wage push inflation is somewhat debunked, it is quite clear that supply chain issues can cause higher costs of production that lead to higher inflation for consumers.

However, demand-pull inflation is the more typical type of inflation, and it fits nicely with the quantity theory of money that Friedman worked with to develop his ideas.

Increases in government spending, funded by money-printing operations at the central bank, will lead to more consumer spending and higher gross domestic product. However, it is the sustainability problem that makes this a bad idea. Endless government spending just creates a long term debt crisis, and we can't spend our way out of a debt crisis. It just creates even higher inflation of prices in the end, with much more hardship to follow.

What is Inflation measured by?

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) is the internationally accepted measure of inflation, and it is this measure that is used by our governments and central banks as a target measure i.e. a low target level of around 2% per year is typical, and monetary policy is used to try and keep the actual CPI rate within close proximity of that target.

The consumer price index uses a representative basket of consumer goods which it amends each year to keep up to date with consumption patterns. As the prices of individual items change, the basket as a whole varies in cost, and the overall rate of change in that cost is used as the measure of inflation.

The basket clearly needs to be very large to be representative and reliable, and something like a thousand items are included in it. Each item is 'weighted' to account for relative importance e.g. pencil costs would be less important than wine costs because people tend to spend a lot more on wine each year than they do on pencils.

No price index can capture a perfect estimate of inflation, and no single figure can determine the correct policy action. The main problems with the CPI are discussed below.

Problems with the Consumer Price Index

Items in the CPI Basket

Following on from the 2008 financial crisis that hit the developed world like a sucker punch, questions need to be asked about why the financial authorities chose to ignore housing and real estate prices in the run up to the meltdown.

Of all the prices that change within an economic cycle, rising housing and real estate prices are arguably the most closely aligned with boom periods. Ignoring them (the CPI doesn't include them in the basket) seems naive at best, and negligent at worst.

Not only are these prices well aligned with boom periods, and therefore indicative of the need for a tighter monetary policy, it was specifically the inflation rate of these prices that led to all the junk mortgage-backed securities floating around the banking sector in 2008.

If something had been done sooner, the costly bailout of the banking sector could have been avoided.

Purchasing Power or Economic Performance?

If an estimate of purchasing-power-changes is all that is needed, the the consumer price index may be an acceptable measure. However, given that it is the measure that dictates monetary policy, I would argue that the primary purpose of the CPI should be to reflect the current state of a domestic economy's over-performance or under-performance.

For example, petrol/gasoline is included in the basket, even though its price heavily reflects international supply and demand factors for oil rather than domestic factors, meaning that it is best used as an indicator of how the global economy is performing rather than the domestic economy.

Granted, oil is a hugely important factor in the overall cost of production in an economy, and its influence needs to be taken into account, but it would be far better to do this separately rather than simply bundling it in with other items in the basket.

Conversely, housing costs are not included in the basket, even though they are an excellent item for judging the state of the domestic economy. Housing and real estate costs conveyed almost perfect information for predicting that our economies were heavily overheating in the run up to the 2008 financial crisis, but this information was discarded.

Many manufactured items are included in the basket, with no consideration for where those goods were produced i.e. in the domestic economy or in a foreign country. These items offer almost no credible value for estimating whether domestic economic growth is proceeding at a sustainable level or not.

Quality rather than Prices

Accounting merely for the price inflation of items fails to appreciate changes in the nature of the items themselves. For example, it is a relatively straightforward affair to track how the price of entry level gaming laptops vary over time, but what about their performance? Certain items, and especially those that use/provide advancing technologies, evolve into very different items over time. The consumer price index does attempt to account for these changes, but it fails to do so with any great degree of accuracy.

Even relatively old technologies can change significantly over time, and no one would argue that the cars of 20 or 30 years ago are comparable to the cars of today. Even basic family cars today are built with far superior handling, safety, performance, economy, reliability and so on compared to the cars of previous decades.

Clearly, changes in the quality of a product (over and above changes in the price of that product) add an extra dimension of inaccuracy to the CPI. This is particularly problematic when using the index to estimate changes in purchasing power over time.

Substitution Bias

A final limitation of the CPI is the substitution bias that consumers have when prices change. Most goods and services have a range of viable substitute goods that could be purchased as a replacement for a product that becomes too expensive.

If steak becomes too expensive, and consumers respond by substituting burgers instead, the CPI will tend to understate the true cost of living increase because it will downgrade the significance of steak.

The substitution bias may have a temporary effect or a much longer lasting effect depending on the nature of the market (and price elasticity of demand), but in any case the CPI is not well-equipped to track these sorts of consumer reactions, and to that extent the accuracy of the CPI is further compromised.

Main Alternative Price Indices

- Producer Price Index - this measure provides a better estimate of whether the economic growth path looks sustainable, because it measures the prices of domestic goods and services. However, it is not as good at estimating purchasing power changes.

- Wholesale Price Index - this measure is not really used in western countries, but it does have advantages in estimating costs of production for industries. The downside is that it also fails to do a good job of measuring the cost of living for regular people.

Some Inflation terms

- Headline Inflation Rate - This refers to the costs of all goods and services in the representative consumer price index basket of goods and services. While the usual CPI estimate is seasonally adjusted, the headline rate is not.

- Core Inflation Rate (also called Underlying Inflation) - This is the CPI measure excluding fuel costs and food costs. The justification for this exclusion is that these costs are known to be more volatile upwards and downwards, and therefore create distortions in the measurements.

Why is Inflation bad?

Redistribution Effects of the Inflation Tax

Most people tend to think that it is the richest members of society who have all the money and that, consequently, it is the rich who would be hurt by a debasement of the currency. I'm afraid that this is not the case, the rich are well-protected from inflation, but poorer people are not!

The rapidly expanding size of government budget deficits and national debt is a major worry.

The bulk of a country's national debt is owed to private investment/pension funds that are managed by the country's own financial institutions. If a government were to allow inflation to increase, which it might since it would effectively depreciate the national debt, they would be allowing the depreciation of millions of private pensions, destroying the retirement dreams of millions of hard-working regular people as a result.

The 'Inflation Tax' is a term that has been used to describe the cost of inflation, because it works very much like a hidden tax. People don't tend to notice it in the way that they would notice a bill dropping through their letterbox, but the cost is very real.

Governments have been able to get away with running an inflation tax before e.g., in the 1970s, as a way of paying off the national debt. Much of the outstanding World War 2 debt was eroded by inflation in the 70s, but it remains to be seen if this tactic will be used again.

Price inflation has been the economic public enemy number one for many decades, and it has been kept low for most of that time. However, with debt levels sky high and rising fast, there could easily be a downgrading of our national credit ratings with higher interest rates to follow, which could make it impossible to service the national debt without printing new money into existence. Unfortunately, this type of money-supply growth would likely be the catalyst for even higher inflation in future years.

The richest members of society tend to use their money as security for borrowing and, in times of rising inflation, they do so knowing that they can earn more money from borrowing cash than it costs them in repayments. They do not tend to invest in private pensions or other vulnerable assets, they are much more likely to be wisely invested in inflation-proof equities, precious metals, farmland, foreign assets, and commodities. In 2024, Bill Gates is America's biggest farmland owner!

In fact, while many regular people would have their pensions and savings eroded by inflation, the rich can actually end up making a net profit because their debts are eroded away while their investments are inflation proofed.

Rich people don't borrow in the same way that regular people do. If they own big businesses they can borrow much larger sums than any high street bank will lend to them, and at a much lower effective interest rate. They do this by selling corporate bonds.

Corporate bonds work by raising money for a business in return for an agreed repayment at some future date. The real value, i.e. purchasing power, of that future payment is then eroded away by rising inflation, causing the current value of the bonds to collapse. The rich can then effectively pay off their debts at a fraction of what the bond sales raised.

I wonder if you can guess who tends to buy these corporate bonds... I'm afraid that, once again, it's primarily pension fund managers. The point is that, in these circumstances, the gains made by the rich come directly at the expense of the poor.

So, in effect, rising inflation works like a regressive tax that hits regular people hardest, while the wealthiest people can actually benefit from it.

Hyperinflation of Prices, and Political Volatility

The ever-present threat of losing all control of inflation presents itself when prices just keep spiraling upwards at ridiculously high rates. There have been several episodes in recent world-history of hyperinflation, a situation where a national currency is so rapidly collapsing (technically at a rate of 50% per month or higher) that it falls in value almost as you're looking at it!

Stories abound of people being paid in their lunch hour and then rushing to the bank to get their money deposited where it can earn interest to offset the higher cost of daily life.

Such circumstances make daily life much more burdensome. Economies fail to function effectively in such circumstances, and the volatility that comes with it can give the impetus for massive political change in an extremely bad way. Such was the case in 1930s Germany, with consequences that the world will never forget.

Related Pages: