What is Structural Inflation?

Structural Inflation refers to a situation of rising prices as a result of expansionary monetary policy i.e. excessive creation of new money. Extra money circulating in the economy creates extra demand for goods and services relative to their supply, and this creates pressure for prices to rise via market forces.

The term is intended to be distinct from demand-pull inflation, even though the extra money created rising prices via stimulating demand. The point is that demand can rise or fall in the short term irrespective of monetary policy, so structural inflation is a unique phenomenon, and is just one pathway that can lead to demand-pull inflation.

Some controversy arises over the use of this term because it can be argued that it obscures the original meaning of the term inflation. I'll briefly explain this below, but first I'll start with an explanation of what causes structural inflation.

Later in the article I will go on to explain some false advice given on other websites about what constitutes structural inflation, especially with reference to its counterpart i.e., transitory inflation.

What Causes Structural Inflation?

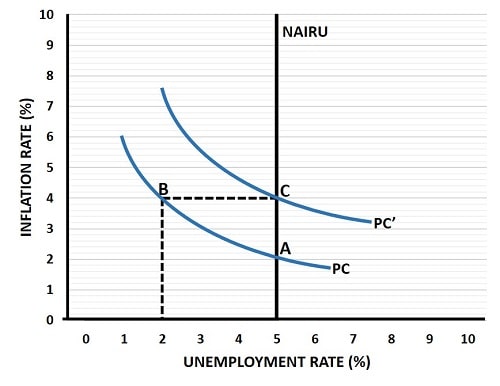

The graph below is taken from my article about the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (NAIRU). The NAIRU is a measure of long-term unemployment that the economy tends towards.

Unfortunately, the government is often tempted to temporarily reduce unemployment when it wants to gain votes. By boosting spending programs and handing out stimulus checks, both of which boost the money supply, the government can reduce unemployment from point A in the graph to point B.

Example of Structural Inflation

In the example above, short-term unemployment falls from 5% to 2% as illustrated by the movement along the Phillips Curve from point A to point B. Unfortunately, the extra spending puts pressure on prices to rise, and the inflation rate increases from 2% to 4%.

This is a structural phenomena. There is no way that unemployment can be maintained at 2%, it is too low. If productivity were to increase proportionately with the increase in spending then there would be no problem, but in that case the long-term unemployment rate would be 2%, not 5%.

If the government attempts to maintain unemployment at 2%, it will require ever increasing amounts of spending and money-supply growth. Ultimately this would end in hyperinflation and total economic collapse.

To prevent this, the government and the Fed will need to take corrective action by cutting spending and raising interest rates. This, of course, will cause unemployment to start rising, and the economy will move from point B to point C in the graph above. Even here, inflation will be permanently higher due to the role of higher inflationary expectations (see my article about the NAIRU for details).

Reducing structural inflation back down to the original 2% rate, at point A, would require a recession i.e., unemployment higher than 5%.

Inflation Vs Rising Prices?

In its original use, inflation did not directly relate to a situation of rising prices in the economy. Instead it simply referred to an expansion of the money-supply. Rising prices were then seen as being a natural consequence of 'inflating' the money supply.

If inflation is a term that describes an increasing money supply, describing the resulting price level increase as structural inflation is somewhat confusing i.e. is 'inflation' used to describe expansion of the money supply or a rising price level? The same word should not be applied to two different meanings.

Of course, the meaning of words can change over time, and this is nothing new. At one time a Xerox machine meant a photocopier produced by the company Xerox. However, since the term became synonymous with photocopiers over many years, Xerox machine simply came to mean photocopier. The company actually lost its copyright on the term!

However, controversy still exists over the correct use of the term inflation, and that's because it has been manipulated by the government for self-serving means.

Government Manipulation

The reason why some economists object to terms like structural inflation is because of the way in which it allows the government to shift the blame for causing prices to rise.

Everyone knows that the government (or the monetary authority i.e. Federal Reserve Bank) is responsible for monetary policy. That being the case, everyone knows that the government is accountable for any expansion of the money supply.

If the term inflation is used in its original sense then all inflation is structural, and the government is responsible for the resulting price increases and extra costs of living. By disassociating the term inflation from meaning an expansion (or contraction) of the money supply, and instead relating it directly to rising (or falling) prices, the government can shift the blame for rising prices onto businesses.

They frequently refer to 'price gouging' on the part of greedy capitalists who are profiteering from the price increases, and they do this even after causing huge increases in the money supply.

I'll leave it to the reader to decide whether or not the term structural inflation is an appropriate term or a manipulation, but it helps to be aware of these controversies.

What Structural Inflation is Not

Structural inflation is not Transitory inflation!

The term transitory suggests a short timeframe, but the relevant timeframe is not defined. A better way to consider transitory inflation is that it is temporary even without corrective action to eliminate it i.e., the market will self-correct and eliminate the problem.

In the aftermath of the 2020 pandemic, the Federal Reserve declared that the rapidly rising price level was a form of transitory inflation caused by supply-chain disruption. It is true that there was massive supply-chain disruption, and so a significant proportion of the inflation after 2020 was indeed transitory.

However, the lockdowns were also combined with an unprecedented expansion of the money-supply as the government sent out stimulus checks to mothballed businesses and workers. The unfortunately named 'inflation reduction act' was also a package of extra spending measures funded by debt fueled spending.

The impact of this enormous expansion of the money-supply, debt and deficit spending, was severe structural inflation. Nothing about this was transitory or self-correcting; it actually required the sharpest increases in interest rates on record in order to bring it down.

Structural inflation is not Bottleneck inflation!

There are many claims that structural inflation relates to structural problems in the market i.e., a mismatch between supply and demand such that suppliers face a bottleneck in their ability to increase supply to meet demand.

Bottleneck inflation would better be described as a form of cost-push inflation, and it tends to be a transitory self-correcting phenomena. Structural inflation is the opposite of this, requiring a slowdown in the rate of money-supply growth to bring it down.

Related Pages: