- Home

- Circular Flow

- Solow Growth Model

Solow Growth Model & Theory

The Solow Growth Model, sometimes referred to as the Solow-Swan model after its two developers Robert Solow and Trevor Swan, offers a simple explanation of how a country's economy expands in the long-run. It is not a short-run model, and has nothing to say with regard to business-cycle booms and recessions.

The applicable time-span relates to decades rather than months or years. Don't allow this to deter you from studying it, because the vital importance of the long-term growth rate of an economy more or less overshadows all other economic considerations regarding the future material well-being of that economy. A short-run economic growth model merely aims for a smooth transition along that growth path.

Small differences in the growth rate of an economy are cumulative, and over time these differences materialize as huge gulfs between the standard of living in one country compared to another.

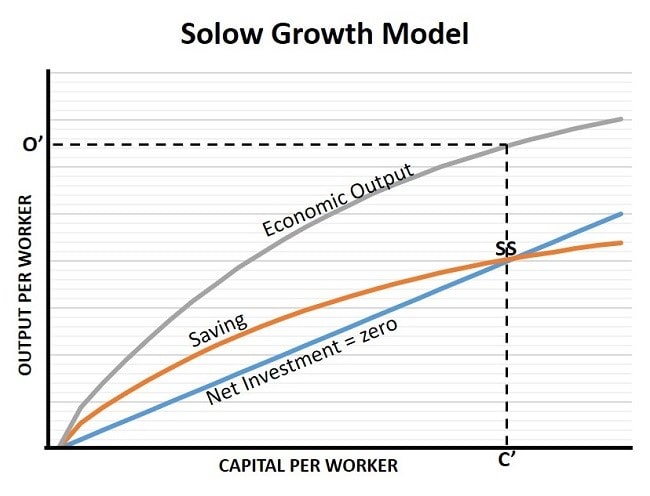

The graph below gives a nice simple depiction of total economic output per worker for an economy at a point in time. For simplicity imagine an economy with no government sector i.e. no taxes or government spending, and no foreign trade.

Also assume that population growth rate is zero, and that the working-age effective labor supply is constant. Finally, we use a simple Cobb-Douglas production function where output is determined by the capital to labor ratio.

These simplifications do not change the key concepts of the Solow model, but they do make those concepts easier to understand, because the economy will settle at a point where saving = investment when there's no government or international trade, see national income accounting for clarity on that.

In the graph, the 'steady state', i.e. the point SS depicts the the equilibrium point with total economic output per worker equal to O' and total capital per worker (including physical capital like machinery, human capital like education, skills & entrepreneurship, as well as natural resources like land, fisheries, oil & gas, coal etc.) of C'.

You might wonder why net investment can equal zero with any positive level of economic output. The key is to remember that net investment is different to gross investment. Gross investment would always be above zero, but a large part of that gross investment simply goes towards replacing worn out, or 'depreciated', capital. Net capital investment is only positive if overall investment is enough to replace depreciated capital and then actually increase the total capital stock in the economy.

The savings rate is assumed (for simplicity) to be fixed, and as mentioned above saving = investment. With low levels of capital workers can greatly increase their output with some extra capital investment, but there are no constant returns, there are diminishing returns to capital. E.g. give a farmer a tractor and he will greatly increase his productivity, give him a second tractor and he'll struggle to make further increases.

The Solow Growth Model Steady State

In the graph, the straight 'net investment = zero' line intersects the sloped saving line at SS. If the economy was performing below O' and C' then saving would be higher than investment and, with nowhere else to go, that saving would have to increase investment and move the economy towards the steady state. You might think that the extra saving could go towards extra spending, but don't get confused by this because, by definition, saving is the same as non-spending. So, if I save and you borrow my savings to go spending, then there is no net saving at the level of the economy.

If output was higher than the steady state, then there would not be enough saving to sustain investment levels necessary to maintain the capital stock, and once again there would be convergence back to the steady state.

The Golden Saving Rate & Capital Accumulation

What isn't explained so far is how any particular savings rate is determined, all that is said is that some level of saving will occur.

This is an important omission, and one that we turn to right now.

The saving rate is clearly a very important determinant of economic well being since more saving equals more investment i.e. capital accumulation, with a higher equilibrium output. But what is the optimal level of saving? A saving rate of 100% is not possible, and not even desirable, because the desired outcome is not higher output itself but rather a higher level of consumption. If savings are 100% then nothing is left for consumption and our standard of living will be rock bottom.

Similarly, if the saving rate is zero, then there will be no money available for investment and ultimately the capital stock will depreciate until it is completely worn out and useless, at which point our output level would be rock bottom with close to zero consumption.

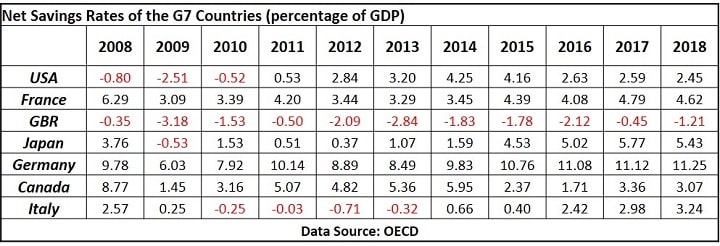

Clearly, the optimum level of saving, also known as the 'Golden Saving Rate' is somewhere between 0% and 100%. Whilst the precise rate may vary between different countries and different circumstances, economic research strongly suggests that most of the western world is operating well below the golden saving rate.

As you can see from the table above, the level of net saving for much of the western world has been worryingly low since the 2008 crisis, and this poses a serious threat to living standards in the coming years.

The 'Solow Residual' Theory

You may have noticed that the model so far appears a little too simplistic given that it has placed all of the emphasis for balanced growth on capital accumulation. The bigger picture does, however, include a sort of catch-all metric that accounts for growth that is not attributed to the capital to labor ratio - and that is known as the Solow residual.

The primary driver of the Solow residual is technological advances.

Technical progress is extremely important for raising total output, and its importance is amplified in the less developed economies. That might seem counterintuitive at first glance, but on second glance you should quickly realize that less developed countries can achieve rapid growth simply by upgrading their existing technologies to the more advanced and productive technologies that exist in the developed world.

The developed world on the other hand tends to already be using cutting-edge technology, and only expensive research and development into brand new production techniques can yield further long run economic growth.

Whilst the Solow model (and all neoclassical growth models) is concerned primarily with the benefits of promoting a shift towards the Golden rule saving rate, and does little to examine the nature of technical progress, there are some complementary/alternative models that put the emphasis on explaining the drivers of technology improvements.

One of the reasons for the development of these models surrounds the general dissatisfaction with the Solow growth model's prediction that economies with differing saving rates need not have different growth rates i.e. once at a steady state is reached any further growth is simply attributed to the Solow residual. The real world economic record does not support this prediction, and shows that higher long-term growth rates are indeed associated with higher saving rates.

The most well-known of the technology-focused models is called:

That will be the focus of another article, but for now I want to continue with a look at some of the main objections to growth as a policy objective at all.

Concerns about Economic Growth

I appreciate that, to a growing number of people in western countries, economic growth might not be seen as a desirable objective. The reasons for this concern are many and varied, but I think that the two most common objections are:

- That growth will cause catastrophic climate change.

- That growth necessarily comes with more inequality.

With regard to pollution, this may be a valid concern if it does lead to climate change, but on that I would make two points:

Firstly, the science is extremely complicated and far from conclusive, whilst also being highly politicized. The main agencies charged with researching the effects of carbon emissions on the climate will NEVER report that there is nothing to fear.

I can tell you from personal experience that any government funded agency's primary objective is its own continuance. It is naive in the extreme to imagine that any organization that is receiving vast sums of public sector money to research any given problem will ever report back that there is no problem, and therefore no need for further funding from the government.

This does not mean that we should dismiss any concerns about potential damaging effects of economic growth on climate change, just that the so-called science on the topic is highly uncertain, politically motivated, and institutionally biased.

Secondly, regardless of whether or not economic growth causes potentially devastating consequences for the climate, there is no way that any lower or middle income countries could, or should, be persuaded to abandon growth as an objective. Some commentators argue that the rich developed world should lead the way on cutting carbon emissions as an example to other countries, but this is poorly thought through.

Imagine a poor parent in the third world explaining to her children that tonight they should not light a fire, meaning that they should go cold and hungry, because people in the west have started buying hybrid 4X4 cars instead of the gas guzzlers they used to buy! This western example is not going to convince anyone, and nor should it.

Only technological progress can solve the potential problems of carbon emissions, and that is usually best achieved alongside economic growth.

On the second concern, regarding inequality, I have written more about this on my page about inequality, here I will merely report that economic growth does not imply any increase in inequality, it actually seems to reduce it, and I'd encourage you to click the link for more information if you are not convinced.

Solow Model Lessons for Applied Economics

Whilst the Solow model clearly uses a very simplistic production function that only includes capital and labor, it does highlight the importance of the saving and investment rate in a country as a key determinant of achieving a high level of income per capita.

For less developed countries in particular, where vast technological progress can come by simply adopting the existing technologies of more developed countries, the saving rate is almost certainly the most important determinant of long-run growth.

For highly developed economies the model paints a less complete picture. For these economies, understanding and promoting the key drivers of technological advancement becomes more critical for higher growth rates, and more work on relating all that to the saving rate in a country needs to be done.

The practical economics lessons for much of the western world have been clear for decades, and ritually ignored for decades! Governments seem obsessed with propping up current consumption levels rather than saving levels because, in the short run at least, more saving leads to lower economic output not higher economic output (the so-called paradox of thrift), and that might come with a loss of popularity at the ballot box!

Trade deficits, i.e. higher levels of imports than exports, have long been balanced by capital inflows in the form foreign firms purchasing government bonds, which simply increases our country's indebtedness and in effect finances current consumption at the expense of future consumption.

There is a strong argument that government borrowing 'crowds out' private sector investment. This is because, with limited money being saved in the first place, there is only so much available for investment purposes, and this pot of money is further reduced if it is used to plug the gap in the government's finances.

Finally, the standard neoclassical growth models make no attempt to account for any externalities associated with economic growth and have nothing to say about market emission quotas for example. The 'Green Solow Model' by Brock & Taylor is a more modern adaptation that does include environmental impact within its function.

What is the Solow Growth Model, and who developed it?

What is the Solow Growth Model, and who developed it?

The Solow Growth Model, developed by Robert Solow and Trevor Swan, explains long-term economic growth by examining capital accumulation, labor, and technological progress. It is focused on long-run growth, not short-term business cycles.

What time span does the Solow Growth Model apply to?

What time span does the Solow Growth Model apply to?

The model applies to the long-run, over decades rather than months or years. It’s concerned with long-term economic trends, making it crucial for understanding the material well-being of economies over time.

How does the Solow Growth Model relate to standards of living?

How does the Solow Growth Model relate to standards of living?

Small differences in economic growth rates, as explained by the Solow model, compound over time, resulting in large disparities in the standard of living between countries in the long term.

What assumptions does the Solow Growth Model make about the economy?

What assumptions does the Solow Growth Model make about the economy?

The model assumes:

- No government sector (i.e., no taxes or government spending)

- No foreign trade

- Constant population growth rate

- A Cobb-Douglas production function, where output depends on the capital-to-labor ratio.

What is the steady state in the Solow Growth Model?

What is the steady state in the Solow Growth Model?

The steady state refers to the point where the economy achieves equilibrium, with total economic output per worker stabilizing. At this point, saving equals investment, and the economy maintains a constant level of capital per worker.

What role does saving play in the Solow Growth Model?

What role does saving play in the Solow Growth Model?

Saving is crucial for investment and capital accumulation. In the model, the saving rate is assumed to be fixed, and in a simplified economy, saving equals investment. Higher saving leads to more capital accumulation, increasing long-run economic output.

What are diminishing returns to capital in the Solow Model?

What are diminishing returns to capital in the Solow Model?

Diminishing returns mean that while increasing capital can boost productivity, each additional unit of capital contributes less to output than the previous one. For example, giving a farmer a tractor increases productivity significantly, but a second tractor adds much less.

What is the Golden Saving Rate?

What is the Golden Saving Rate?

The Golden Saving Rate is the optimal rate of saving that maximizes consumption per worker in the long run. It balances the need for investment to grow the economy without reducing consumption too much.

Sources:

Related Pages: