- Home

- Market Failure

- Public Goods

Public Goods in Economics, Explained

In economics, public goods are goods that are characterized by two main features i.e., they are non-rival and non-excludable. These unique characteristics mean that public goods are often inefficiently provided by private markets, leading to clear examples of market failure and an inefficient allocation of resources.

I'll start with an explanation of what 'non-rival' and ‘non-excludable’ means:

- Non-Rival - A good is non-rival if one person’s consumption does not diminish the availability of the good for other consumers. This means that the marginal cost of providing the good to an additional consumer is essentially zero.

- Non-Excludable - A good is non-excludable if it’s difficult or impossible to prevent individuals other than the purchaser from using it. This creates what is known as a free-rider problem because individuals can benefit without contributing financially.

Examples on non-rival goods include a lighthouse or public television broadcast. Once a lighthouse is functioning, one more ship using its signal does not add any cost, just as one more viewer does not increase the cost of a public broadcast.

National defense is a classic example of a non-excludable good because, once it is provided, it benefits all citizens regardless of whether they contributed to its funding.

These two characteristics make public goods very challenging, if not impossible, to supply efficiently through private markets. This is because producers cannot easily charge consumers as there is little incentive for any individual consumer to pay voluntarily. Instead, many public goods are provided or subsidized by governments in order to ensure they are available at a socially efficient level.

The Free-Rider Problem

Market failure with public goods arises from the free-rider problem. Since people can benefit from non-excludable goods without paying for them, they are often underprovided in a market setting. For instance, a community might benefit from a mosquito control program worth many thousands of dollars, but if people can benefit for free once it is installed, few will volunteer to pay for it thereafter.

This lack of voluntary contribution means that the program might be impossible to provide profitably by the private market, and therefore requires government assistance.

A government will often step in to either subsidize private provision of these goods, or directly provide them by itself. In the latter case, instead of charging a price for public goods in the marketplace, they fund them through taxation, ensuring that sufficient funds are available to provide enough goods at a level closer to a socially optimal quantity.

Measuring Demand for Public Goods

Efficient provision of public goods requires a different approach to measuring demand than that for private goods. With private goods, demand is based on the marginal benefit for each individual, added horizontally across consumers. But for public goods, the aggregate demand is determined by vertically summing the marginal benefits of each person.

For example, if two consumers each value an additional unit of a public good at $3 and $2, respectively, the total marginal benefit for society is $5. This vertical summation gives us a clearer picture of the marginal social benefit, which is key for determining the efficient provision level. The socially optimal quantity of a public good occurs where the marginal social benefit equals the marginal cost of production.

Types of Goods and Market Provision

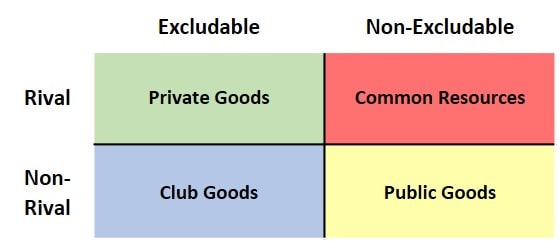

Economists categorize goods based on their rivalry and excludability, creating a framework that helps explain why some goods are better suited for private markets while others are not.

- Private Goods (Rival and Excludable): Private goods like food, clothing, and electronics are both rival (consumption by one person reduces availability for others) and excludable (producers can charge for them). This allows markets to supply private goods efficiently, as producers can capture payments for their production costs.

- Public Goods (Non-Rival and Non-Excludable): True public goods, such as national defense and clean air, are available to everyone and difficult to restrict. Without government intervention, these goods are often underprovided due to the free-rider problem and inability to capture payments directly.

- Common-Property Resources (Rival but Non-Excludable): Resources like fisheries, water bodies, and forests are rival in consumption but non-excludable. Since individuals can overuse these resources, they often suffer from overconsumption, leading to depletion (a phenomenon known as the "tragedy of the commons.") Governments or regulations may impose limits or access rules to preserve these resources and avoid market failure.

- Club Goods (Non-Rival but Excludable): Club goods, like subscription-based services or toll roads during off-peak times, are non-rival (an additional user does not significantly impact others) but excludable (access can be restricted to paying customers). Since providers can charge for these goods, they are typically supplied efficiently by private markets or through membership fees.

Examples of Public Goods: Excludable vs. Non-Excludable

Public goods can sometimes be made excludable with sufficient technology or regulatory control. Here are examples of each:

- Non-Excludable Public Goods: National defense, clean air, street lighting, mosquito abatement programs, public fireworks displays, and free public broadcasting are all non-excludable. These goods provide broad social benefits, making them difficult for private markets to supply without free-rider issues.

- Excludable Public Goods: Examples include toll roads, museums with entrance fees, subscription-based public television, and private parks. Here, access can be limited, making it possible to fund these goods through user fees, though they still provide societal benefits.

Externalities and Public Goods

Public goods usually exhibit externalities, because their benefits often spill over to non-payers. For instance, public health measures benefit everyone by reducing disease spread, not just those who directly contribute financially.

Similarly, common-property resources create negative externalities when overuse by individuals leads to resource depletion, harming others’ access to these resources. Government intervention can reduce these inefficiencies through regulations or provision of certain goods.

Conclusion

Public goods represent a unique challenge for markets due to their non-rival and non-excludable nature. The free-rider problem, coupled with the difficulty of capturing social benefits, often results in market failure. Understanding the distinctions between public goods, common-property resources, and club goods helps clarify why government intervention is frequently necessary to provide these goods efficiently.

By equating marginal social benefits with marginal costs through public funding and regulation, governments play a key role in overcoming market failure and ensuring that society can access the essential benefits that public goods provide.

Related Pages:

About the Author

Steve Bain is an economics writer and analyst with a BSc in Economics and experience in regional economic development for UK local government agencies. He explains economic theory and policy through clear, accessible writing informed by both academic training and real-world work.

Read Steve’s full bio

Recent Articles

-

What Happens to House Prices During Stagflation?

Jan 02, 26 09:39 AM

Discover how house prices and real estate behave during stagflation, with historical examples and key factors shaping the housing market. -

Bank Reserves, Asset Inflation, and the Risk of Future Price Inflation

Dec 19, 25 04:16 AM

Learn what bank reserves are, how they affect asset prices, and why future reserve creation could lead to inflation through commodities and currencies. -

Credit Creation Theory; How Money Is Actually Created

Dec 16, 25 03:07 PM

Explore how modern banks create money through credit creation, why the money multiplier fails, and the role of central banks and reserves. -

U.S. Industrial Policy & The Unfortunate Sacrifice that Must be Made

Dec 12, 25 03:03 AM

U.S. Industrial Policy now demands a costly tradeoff, forcing America to rebuild its industry while sacrificing bond values, pensions, and the cost of living. -

The Global Currency Reset and the End of Monetary Illusion

Dec 07, 25 03:48 AM

The global currency reset is coming. Learn why debt, inflation, and history’s warnings point to a looming transformation of the world’s financial system.