- Home

- Business Cycle

- Operational Lag

Operational Lag in Economic Policy, Explained (with Examples)

Operational lag in economics refers to the time lag that occurs between a new policy being implemented and the real effects that it will bring on the economy i.e., the level of GDP. This particular lag is known by many different names, which I will mention, and it varies in duration depending on whether it relates to fiscal policy or monetary policy.

Until recent times, monetary policy had long been the main instrument for managing short-term fluctuations in economic output, with fiscal policy only being implemented in times of severe long-term shocks to GDP. Things have changed in the aftermath of the 2008 great recession, and monetary policy has been maxed out for an extended period (with interest rates set to near zero rates) all so that an inevitable correction could be delayed for as long as possible.

By 2022, with inflation spiraling out of control, any attempt at stabilizing GDP in the years ahead will likely prove futile. This, however, is a reflection of the inappropriate handling of economic policy over many decades prior to our current situation, rather than a refutation of the theory when handled correctly.

As is so often the case, the government is to blame for our current woes, but let's start with an examination of what operational lag is.

The Outside Lags of Stabilization Policy

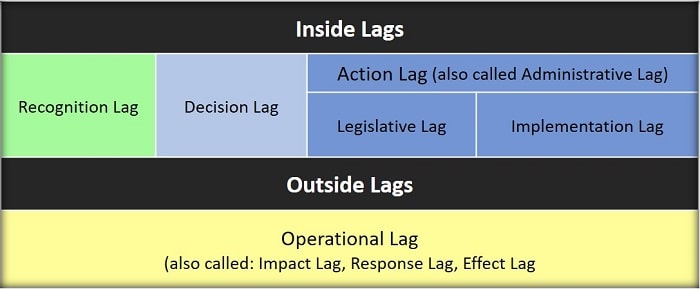

Operational lag is just one of the five main types of lag in economic stabilization policy, and I've explained the other types in separate articles on my site - see the links below for information on that. For now, a chart will suffice to illustrate the breakdown of relevant lags in stabilization policy:

As you can see in the chart, operational lag has many alternative names. I've listed the main ones but there may be others. Impact lag, Response lag, Effect lag and Transmission lag in economics are all popular alternatives which appear to mean exactly the same thing, so they can be used interchangeably.

The most important thing that distinguishes operational lag from the other types identified in the chart, is that it is an 'outside lag' meaning that it relates to the time taken for an intervention in the economy to actually take effect. The other types of lag are all inside lags because they are internal to the recognition of a problem and the actions taken to address it, by contrast the outside lag is external to that process.

Another important distinction is that the lag here is a 'distributed lag' meaning that there is a gradual build up of effects taking place in the economy over time as a result of whatever action is implemented, rather than a 'discreet lag' whereby the full impact occurs all at once after some passage of time. The inside lags are all discrete lags, only the outside lag is a distributed lag.

For details on the other sorts of lags, see my articles at:

Fiscal Policy Vs Monetary Policy Lags

Expansionary fiscal policy and contractionary fiscal policy both operate more immediately and directly on the real economy once all their inside lag delays are overcome, and therefore the associated outside lag is much shorter.

By contrast, monetary policy has a much shorter inside lag since the monetary authority, i.e., the Federal Reserve in the United States, can meet as required and agree upon a course of action within days. Whatever is agreed can then be acted upon immediately via the open market operations desk, meaning that there is almost no action lag (also called administrative lag - see chart above), only recognition lags occur to the same extent in monetary policy as fiscal policy.

Where monetary policy is slower than fiscal policy is the outside lag. The operational lag here takes longer because of the distributed lag effect described above. For example, whereas a fiscal policy expansion might send stimulus checks directly to citizens to encourage spending right away, a monetary policy interest rate reduction will take time to encourage new investment and so on.

Operational Lag Examples

Once a policy is in operation, the time taken for it to impact the economy depends on the extent of the distributed lag effect. Recent examples include:

- Stimulus Checks - these were sent out by the government in order to support people during the Covid-19 pandemic because people were prevented from going to work to earn their income. The checks were readily used with little delay once they were received.

- Interest Rate Hikes - In March 2022 the Federal Reserve made its first interest rate increase in response to growing concerns over rapidly rising inflation. In some ways the impact of this was immediate and/or preempted because the financial markets had already anticipated it, but in other ways it will have much slower effects as the business community and consumers respond to the increasing cost of loans, mortgages and other types of finance.

Conclusion

We might assume that the shorter action lag of monetary policy, compared to tax and spend fiscal policies, makes it more effective as a means of stabilizing the economy when an economic shock of one sort or another takes its toll. Indeed, in all but the most severe shocks over the past few decades our governments have favored monetary policy, but in this article and others regarding policy lags I have only presented an overview of the theory. Practice is not the same as theory, and serious questions arise about the competence of governments and central banks to use such tools.

One cursory glance at the state of the public finances, our national debt levels, our budget deficit and out trade deficit, should answer the big question about whether or not the government can be trusted with the management of the economy in the long run, but even in the short run we should demand more answers, because there is little evidence that the supposed intended effects of any of these policies have been competently handled.

There are just as many arguments to suggest that stabilization policies have been deliberately abused for short term gain e.g., by inappropriately boosting the economy ahead of an election in order to create a temporary feel-good-factor among voters.

If as a society we can learn the lessons of past failures, we might demand less interference from self-serving politicians, but unfortunately there's little evidence of that sort of general public sentiment so far.

Sources:

Related Pages:

About the Author

Steve Bain is an economics writer and analyst with a BSc in Economics and experience in regional economic development for UK local government agencies. He explains economic theory and policy through clear, accessible writing informed by both academic training and real-world work.

Read Steve’s full bio

Recent Articles

-

Circular Flow Diagram in Economics: How Money Flows

Jan 03, 26 04:57 AM

See how money flows through the economy using the circular flow diagram, and how spending, saving, and policy shape real economic outcomes. -

What Happens to House Prices During Stagflation?

Jan 02, 26 09:39 AM

Discover how house prices and real estate behave during stagflation, with historical examples and key factors shaping the housing market. -

Bank Reserves, Asset Inflation, and the Risk of Future Price Inflation

Dec 19, 25 04:16 AM

Learn what bank reserves are, how they affect asset prices, and why future reserve creation could lead to inflation through commodities and currencies. -

Credit Creation Theory; How Money Is Actually Created

Dec 16, 25 03:07 PM

Explore how modern banks create money through credit creation, why the money multiplier fails, and the role of central banks and reserves. -

U.S. Industrial Policy & The Unfortunate Sacrifice that Must be Made

Dec 12, 25 03:03 AM

U.S. Industrial Policy now demands a costly tradeoff, forcing America to rebuild its industry while sacrificing bond values, pensions, and the cost of living.