- Home

- Monetary Policy

- Loanable Funds Theory

Loanable Funds Theory Revisited

The classical Loanable Funds Theory of interest, saving and investment enjoyed its heyday in the years before John Maynard Keynes unveiled his General Theory on the world of economics.

There is no question that Keynes contributed many new and ingenious insights into the workings of the monetary system, and the way in which investment spending and interest rates are determined, but the science was never settled and many bones of contention remain between Keynes' model and the classical school's amended version of the loanable funds model.

In this article I will present the basic loanable funds model before going on to explain the main points behind Keynes' criticisms of it, and the amendments that have been made to it. I will then provide an assessment of current thinking on the theory as well as some personal interpretation of the salient points.

Classical Supply & Demand Model of Money & Interest

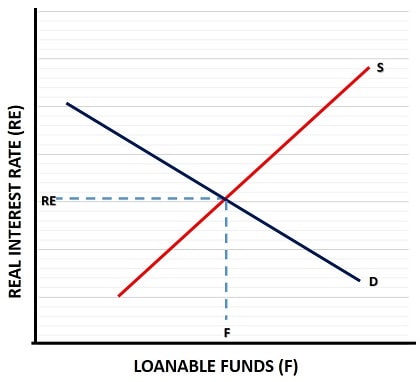

In the classical model, just as in any simple supply and demand model for a normal good, the demand money for investment purposes is equated with the supply of money from savers at a market clearing rate of interest.

The downward sloping demand curve represents the demand for loanable funds (i.e. money for the purpose of investment). At higher interest rates less money is demanded since repayment costs are higher.

The real interest rate payable on a loan (i.e. the rate after adjusting for inflation) is effectively the price of the loan.

Conversely, the supply of loanable funds comes from savers, and they will happily increase that supply in return for a higher real interest rate.

Here’s the important point to remember – this classical model does not include the role of the fractional reserve banking system in the creation of credit out of thin air, i.e. regardless of the supply of money from savers, and for that reason it is an incomplete model.

Note here that I’ve merely stated that the model is incomplete, not that it is undesirable.

The classical model would be much more accurate in an economy without a fractional reserve banking system, and in an age of global debt crises there are a growing number of economists who feel that scrapping the current monetary system in favor of full reserve banking, or a sound money alternative, would be a very desirable step in the right direction.

Loanable Funds Theory Amendments

The earliest amendments to the classical model into a loanable funds doctrine that includes excess credit expansion, have been attributed to Knut Wicksell and dates back as far as the late 19th century. At that time Wicksell was attempting to explain the relationship between inflation and the rate of interest (which the classical model was failing to do).

Wicksell started with the assumption that the Quantity Theory of Money would provide an accurate account of changes in prices and interest rates in an economy where excess credit creation by the banks does not exist i.e. where the supply and demand for loanable funds is allowed to clear at a natural interest rate.

However, in a fractional reserve system such as we have today, there will be discrepancies in the gap between inflation and interest rates. In simple terms, Wicksell argues that in such a system the link between the supply and demand for loanable funds is broken, because the potential supply of credit is not limited to an equal supply of loanable funds from savers.

The Natural Rate of Interest

The implication of a fractional reserve banking system is that the only real short-term restriction on money supply growth is the ability of borrowers to pay the prevailing interest rate on credit. That interest rate may well be different to the ‘natural rate’ that would exist if the market was left to normal supply and demand forces i.e. where actual lenders' savings are matched to borrowers' investments.

This link between savings and investment loans is broken in a banking sector that can create an extra supply of loanable funds via credit expansion alone, without any associated increase in savings.

To the extent that the prevailing interest rate is below the natural rate, this would be consistent with the banks boosting credit levels such that borrowing exceeds saving. In these circumstances it is likely that malinvestment will occur whereby poor investments, with returns lower than would be necessary to pay the natural rate of interest, are routinely being made.

The end result of this will be a boom-bust business cycle, because spending in the economy will outpace the growth of productive capacity i.e. it leads to rising prices followed by recession. In extreme circumstances, such as those in 2022, the real interest rate (after accounting for inflation) can go negative for a prolonged period of time if the government intervenes in the market to keep nominal rates low.

How is the Interest Rate Determined?

The interest rate is determined by the supply of, and the demand for, money. However, money in this context can take the form of credit that has been created by the banks. It is not necessary for savings to equal borrowing, and that breaks the classical model of interest rate determination.

The loanable funds doctrine seeks to amend the classical model by including the impact of credit creation by the banking system.

The problem with the prevailing rate of interest is that it is divorced from the natural rate that occurs when the supply of, and demand for, loanable funds is allowed to clear by itself. It invariably leads to excess supply of credit and fuels economic instability via an exacerbated business cycle.

In reality, interest rates that solely reflect the demand for money/credit (Keynes' Loanable Funds Theory) offer a much better model of the loanable funds market than the unamended classical model, at least in the short-run. The problem is that the short-run can last decades, leading to huge debt accumulation and malinvestment problems with depressed economic growth, before an economic crisis forces reality to re-emerge.

Keynes’ Criticism of the Loanable Funds Model

John Maynard Keynes presents his alternative model of interest rates in his Liquidity Preference Theory. The key difference in this model is that Keynes completely severs the link between saving/investment and interest rates by insisting that only the supply and demand for money influences the interest rate (and the banks can create the supply, hence the broken link with saving).

In the 1930s, Bertil Ohlin, a major contributor to the development of the Loanable Funds Theory along with his colleague Dennis Robertson, responded to Keynes’ criticisms with a challenge for him to use his liquidity preference theory to explain how businesses obtain funds for planned investments.

The Liquidity Preference Theory merely identified three types of demand for money, all coming from consumers i.e. transactions demand, precautionary demand, and speculative demand. Keynes did acknowledge this missing component of his theory and went on to include a ‘financial demand for money’ to account for it. However, he continued to insist that planned investment is not financed by planned saving, and in so doing started a debate that is unresolved to this day.

Despite the unresolved discrepancies in the two views, there are significant areas in which the liquidity preference theory and the loanable funds theory are in agreement. Most notably, both agree that in a fractional reserve banking system the ability of the banks to create vast amounts of new credit irrespective of any increase in savings is the dominant factor influencing levels of interest and borrowing.

There is disagreement, however, about the nature of this borrowing. The loanable funds doctrine maintains that any interest rate discrepancy with the natural rate of interest cannot be maintained in the long-run, and that the rate must ultimately converge with the natural rate. The Liquidity Preference Theory, on the other hand, denies any existence of a natural rate or that any significant amount of malinvestment will result from interest rates that are lower than would be the case in a financial system where investment is equal to savings.

Conclusion about the Theory

I think that in order to appreciate the discrepancies in these two models it is necessary to appreciate the differences in ideology. The Keynesians always start from a position of assuming that there is spare capacity in the economy to increase production without causing inflation.

The Loanable Funds Theory supporters, on the other hand, belong more to the classical school and regard their theory as an evolution of the earlier classical model. They do not start from a position of assuming that the economy has any spare capacity, but rather that any short-term boost will inevitably be unsustainable in the long-run due to rising inflationary pressures.

While I tend to lean more on the side of the loanable funds model, I do think that the ‘short-term’ may in practice be quite long-lasting before any eventual return to equilibrium is possible. In particular I think that the role of the government and the central bank in a fractional reserve system can severely distort the loanable funds market, and resulting interest rates, for decades.

During that time, a fiat based fractional reserve system that is not anchored to anything real, like gold, will inevitably lead to credit expansion and interest rates way below the natural rate. This enables, and encourages, people to take on debts rather than to save. Keynes was focused on investment, but lower costs of borrowing also encourages consumption via credit card spending and personal loans. People can easily fall into a debt-trap, leading to lifelong misery.

If they default on their debts to the extent that the banking system comes under threat of collapse, then the government will inevitable step in with bailouts, severing the need for responsible lending and encouraging a reckless levels of lending by the banks i.e. moral hazard.

As the economy faces a threat of recession, government will act to avert it with discretionary fiscal policy. The problem here is that such policy is almost always akin to malinvestment, because governments are terrible at making sound investments.

Modelling of government incompetence, and corruption, is missing from either the classical school of economics or the Keynesian school. Additionally, the lure of vast profits for the banking sector via excessive credit creation in the short-term, is missed. In these regards I find the Austrian school much more convincing. Their conclusion that a sound monetary system is needed, along with a much reduced role for government intervention in the economy, is difficult to refute.

Active demand management policy has created a world crippled by peacetime debt levels never before seen. The level of saving has been ignored for decades, and only the incessant push to sustain unsustainable levels of consumption has featured as a permanent feature of government economic policy, and that's regardless of which political party has been in power during any given timeframe.

Sources:

Related Pages: