Inflation Vs Deflation Explained (with a Case Study)

In this article about Inflation vs deflation, I will start with a brief analysis of which of these two undesirables is the most damaging to an economy. After that, I will proceed to a more detailed case-study which analyzes which of these two outcomes is more likely to emerge, from a June 2023 start point.

At first glance it might seem strange that there could be any debate over the likely occurrence of two seemingly opposite outcomes. After all, how could it be that a significant probability of a falling price level coexists with a significant probability of rising prices? The answer is that both of these possibilities stem from the same beginnings i.e., deep economic recession, and either outcome could occur depending on the government’s handling of it.

While there are alternative narratives, this report takes it as a given that a deep recession is imminent. There are many diverging opinions, from respected economists on either side of the inflation vs deflation debate, but the truth should reveal itself within a year or two of writing this article.

I will leave my thoughts here unchanged, so that future reflections on it can be made through the perfect vision of hindsight. Naturally, I expect that there are important aspects that I have missed or misinterpreted, but I’ve covered the main talking points as of June 2023.

For anyone who might be interested in my thoughts about the ravages of rising prices, and their redistributive effects, I have written about it extensively in my article about what inflation is, and why it is bad.

Inflationary Vs Deflationary Recession; Which is Worse?

There are very few examples of deflationary recessions in the modern world, meaning few cases that can be used to judge their severity, but the obvious exception is the Great Depression of the 1930s. As the name suggests, it was very bad, with unemployment peaking at 24.9% of the workforce. Prices fell by about 30% as roughly 30% of the money-supply was destroyed by uninsured bank failures (this was before the days of bank bailouts!).

While the Great Depression represents the worst economic crisis in modern US history, it pales into insignificance compared to the worst extremities of an inflationary recession. There have been many cases of hyperinflation in various countries around the world, with some of them quite recent e.g., Venezuela suffered it as recently as 2018. The most well-known example occurred in Germany in 1923, with mass starvation and the total breakdown of society as a result.

In terms of which is worse, it seems clear that an inflationary recession presents the greatest danger. Of course, there are relatively mild cases of inflationary recession e.g., the stagflation that occurred in the US during the late 1970s and early 1980s only resulted in an official unemployment rate of around 13%. Nevertheless, at the extremes, hyperinflation is far worse (click the link for evidence of that).

2023 Case Study: The Prospect of Inflation Vs Deflation

The case study below assumes that a major recession is coming to the western world soon. The timing of that is unclear, and there are some economists who argue that recession can be avoided altogether. Nevertheless, I assume that a deep recession will soon hit the western economies.

The study is divided into the main arguments for each of inflation and deflation in the coming months and years. I will start with the arguments for deflation (or at least reduced rates of inflation) because 1) this is the most usual outcome when recession occurs, and 2) I personally favor the counterargument that predicts inflation, so I’ll save it for later.

The Argument for Deflation 1: Yield Curve Inversion

The first argument for deflation is grounded in the opinion that the financial markets are anticipating a cut to interest rates in order to fight against an impending recession. For this reason, the yield curve has inverted (meaning that the interest rate on short-term Treasury bills is higher than that for long-term bonds).

This is, of course, a highly irregular scenario because investors will ordinarily demand a higher interest rate for committing funds for a longer period of time. With a yield curve inversion, the opposite situation is occurring, but the question is why?

With many economic indicators suggesting that there is the threat of a serious recession ahead, the argument is that aggregate demand will fall relative to aggregate supply, causing deflation in the price level.

This is the critical point; a yield curve inversion occurs whenever the market is expecting an interest rate cut in the near future, and the market almost always expects such a cut when the economy appears to be heading into recession. Note, however, that interest rates will not always be cut. If the Federal Reserve believes that high inflation is ingrained, it will be reluctant to cut rates even if recession is imminent.

It is true that most recessions bring deflationary pressure, because falling sales in such times encourage firms to cut prices, but this is not universally true. In the relatively rare case of an inflationary recession, the driving force behind it is a supply-side contraction in the economy that increases production costs and causes prices to rise even as the economy contracts.

Such an event occurred in August 1978 when the yield curve inverted due to market expectations of recession and interest rate cuts. That inversion was the longest on record, lasting almost continuously for 3 years, but the market was wrong! Paul Volcker (the incoming Federal Reserve Chairman) sharply increased interest rates in his fight against inflation.

Some economists believe that the yield curve inversion in 2023 suggests that the market is expecting a deflationary recession ahead, and that an interest rate cut will be necessary to fight it. However, this belief may be misguided. Argument 1 for inflation (see below) shows that a potential liquidity crisis may be driving the yield curve inversion, rather than any expectation of a deflationary recession.

The Argument for Deflation 2: Money-Supply Contraction

With everything else equal, if the money-supply is contracting, we should start to see consumer prices falling as predicted by the quantity theory of money. Unfortunately, the standard measure of the money-supply that most commentators use (M2) has some major shortcomings, and it cannot be used reliably in conjunction with the quantity theory of money.

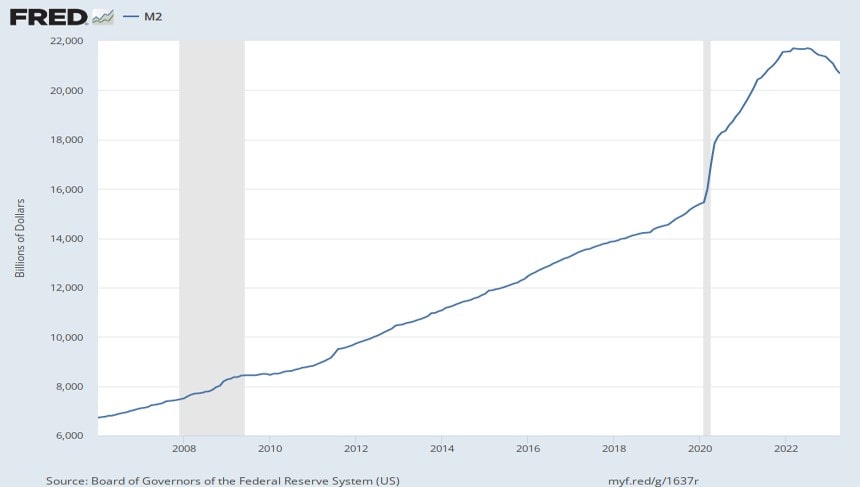

Since April 2022 there have been some falls in the money-supply as measured by M2, but it is small compared to the mountain of growth which occurred in the 2-years prior. We may be on the reverse side of that mountain, but we’re still on a mountain, and it seems unlikely that this will be sufficient to cause deflation. Nevertheless, the recent fall in M2 is being used to predict deflation ahead.

US M2 money-supply growth, Jan 2006 to April 2023.

US M2 money-supply growth, Jan 2006 to April 2023.The main problem with M2 is that it is a very poor proxy for the money that is circulating in the real economy i.e., in the market for goods & services rather than in the market for financial assets. There's no doubt that a massive proportion M2 growth since way back in 2009 has flowed directly into financial assets like stocks and bonds, and much less into goods & services. This is evidenced by the so called 'everything bubble' in financial assets that began way back in 2009, and peaked in late 2021.

Of the explosion of M2 in 2020, and subsequent contraction since 2022, this has deflated asset prices significantly but general inflation in the real economy persists. It seems that while M2 is contracting, a larger proportion of what remains has been entering the real economy. This is evidenced by the extra debt-fueled spending on consumer goods as people run up credit cards and overdraft facilities, and also by the selling off of their overpriced financial assets in order to fund consumption.

M2 also fails to tell us anything about the velocity of circulation, which is another important consideration that has to be accounted for before inferring anything about inflation/deflation.

In summary, we cannot simply assume that the recent M2 contraction will lead to significant reduction in aggregate-demand for goods and services, and certainly not to the extent that it will cause a deflationary recession. There has, of course, been significant disinflation over recent months, but that has resulted from falling investment levels and the 'Bullwhip Effect' rather than falling consumer spending. This would seem to herald a coming supply-side contraction as firms slowly contract production (see the argument for supply-side problems below).

An additional factor in support of the case for deflation can be made with respect to the interest rate increases that have already been implemented since 2022. Monetary policy is known to work with a long ‘operational lag’ of 12-18 months before it starts to take effect, and that would mean that previous rate rises should start to take effect anytime now.

It is true that these rate rises should soon start to impact the economy, and this is another reason why this report takes imminent recession as a given. However, it remains to be seen whether or not the monetary tightening and rate rises will be enough to create a deflationary environment.

Critics are quick to point out that the rate rises have failed to achieve positive real rates, because the inflation rate remains higher than the nominal interest rate. The rates offered on savings accounts are particularly meagre, and so it is doubtful that anyone has been deterred from spending in favor of saving. It is true that borrowing costs have risen significantly, and this will have deterred some credit fueled spending, but there is little evidence of any actual contraction in such spending. All this points to limited overall effects on spending, and thus limited reason to expect deflation.

The Argument for Deflation 3: The Strong US Dollar

When the US Dollar is strong, it enjoys a relatively high exchange rate against other currencies meaning that imported goods are relatively cheap. As a result, demand for those imports will be high and, conversely, demand for the relatively more expensive domestic goods will be lower. Cheap imported raw materials and other inputs is the production process will help to keep costs of production lower thereby creating deflationary pressure.

If the outlook for the dollar suggests that it will increase in value, it would suggest that there is some deflationary pressure in future. The argument for a strong dollar in the coming months and years is based on Brent Johnson’s ‘dollar milkshake theory’. The idea is that as recession comes to the major western economies, it will create a liquidity crisis (see argument for inflation 1 below) which foreign investors will respond to by switching away from failing domestic securities in favor of US securities. The extra demand for US securities will then cause a US Dollar appreciation.

In the short-term the dollar milkshake theory may well work as predicted, because international investors do seek to hold assets denominated in the world’s reserve currency during troubled times. In that case it will work to boost the US dollar and create some deflationary pressure. However, the wider global pressures on the financial system suggest a very different long-term trend. De-dollarization has already begun, with many countries (especially the BRICS countries) moving away from dollars in favor of hard assets like gold.

As the US dollar gradually loses its status as the global reserve currency, demand for dollars will fall, and the dollar exchange rate will fall with it. Additionally, current global holdings of dollars will gradually be repatriated as this process unfolds, thereby boosting the US money-supply and creating inflationary pressures.

The Argument for Inflation 1: The Liquidity Crisis

It is doubtful that the yield curve inversion in 2023 is a reflection of the market’s anticipation of a deflationary recession, rather it seems far more likely that the market is anticipating an imminent liquidity crisis in the entire financial system given that several US banks have already collapsed this year. In such circumstances, an interest rate cut may well be necessary in order to inject extra liquidity into the system.

In other words, irrespective of adding fuel to the inflation fire, an injection of money into the system via lower interest rates may be unavoidable if the Fed wants to avoid a financial system meltdown.

During the long period of near zero interest rates, from 2009 to 2022, the banking and finance sector bought massive amounts of long-dated bonds. Many pension companies actually leveraged their accounts in order to buy even more bonds so that extra returns could be earned. The paltry returns available on these bonds made such leveraging necessary if these pension funds were ever to be able to afford comfortable retirement payments for their customers.

Unfortunately, with a huge exposure to the leveraged buying of bonds, the financial sector is extremely vulnerable to any falls in the market-price of those bonds. This is because they account for a huge proportion of the sector's assets. If assets fall in value, relative to liabilities, bank-runs and other financial sector runs could make many institutions insolvent.

Bonds have a sale price that is inversely related to interest rates, that’s because they are fixed-return assets. When the interest rates on alternative financial assets increase, the demand for bonds decreases until their price falls to a level that is competitive with those alternative assets. For this reason, interest rate rises threaten to destroy the solvency of many banks and pension fund companies.

We have already seen evidence of this threat in late 2022 when the incoming British Prime Minister, Liz Truss, adopted a policy of tax cuts without any accompanying spending cuts. This caused panic in the financial markets because it threatened to create extra inflationary pressure at a time of already high inflation. If the inflation rate were to increase, interest rates would have had to rise to fight against it, thereby causing the bond market to collapse.

The tax cutting policy was quickly abandoned, with huge amounts of bailout money provided to pension companies. This did stabilize the markets, but it ended Liz Truss’s term in office after less than 2-months in the job!

All this is to highlight the fragility of the financial markets at the current time. Higher interest rates (to fight persistently high inflation) are extremely destabilizing, and the yield curve inversion explained above might well exist simply because the market understands that the liquidity crisis is not over.

Rather than cutting rates to avoid a possible deflationary recession, the market may have noticed that the demand-side of the economy is still strong, fueled by robust consumer spending. The expectation of interest rate cuts, as evidenced by the yield curve inversion, may simply reflect the high probability of the Fed being forced to cut rates in order to avoid another liquidity crisis in the financial sector.

If so, then we should expect much more inflationary pressure in the coming months and years, because lower interest rates (and possibly many more bank bailouts) will increase the money-supply and boost aggregate-demand even as the supply-side of the economy is contracting.

The Argument for Inflation 2: Supply-Side Problems

The aforementioned long period of near zero interest rates after the 2008-09 financial crisis led to the formation of many ‘zombie companies’ i.e., companies with tiny profit margins. The malinvestment that has occurred since 2009 is substantial and, in 2023, we are already witnessing a wave of redundancy notices as these companies fight for survival.

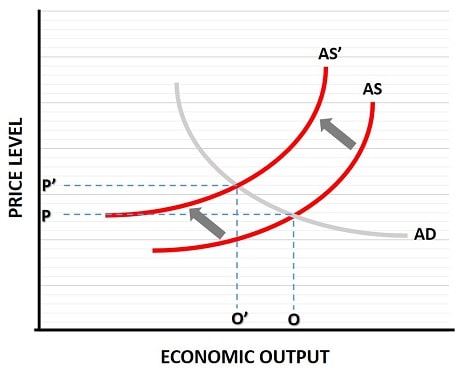

Furthermore, global supply-chains remain strained following the 2020 pandemic lockdowns, meaning that some materials/parts are unavailable, and that many input costs remain elevated. This is best illustrated by the AD-AS Model.

An aggregate-supply contraction causes falling GDP and rising prices at the same time.

An aggregate-supply contraction causes falling GDP and rising prices at the same time.It is true that some input costs have fallen sharply, most notably oil, but the current oil price is reflected in the futures market. Since oil is such an important commodity, the big industrial consumers of oil (and market speculators) enter into contracts today for their future supplies of oil. When recession looks likely in the future, prices today will immediately fall because no one will enter into new contracts without price reductions.

This is precisely what has happened since June 2022, the increased expectation of an economic slowdown has reduced the price of crude oil. However, the underlying price of oil (the price that exists independently of future expectations) is high. This is particularly true in Western countries because of the sanctions placed on Russian oil, in 2022, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The big oil producing countries, OPEC in particular, may well respond to the lower expected demand for oil by cutting supply, in which case the price of oil could soon rise. Whatever happens next, going forward oil is going to be increasingly expensive because all the world’s cheap oil has already been extracted and used. Undoubtedly, the supply-side of the economy will be restrained in coming years, because oil is a big component of the overall costs of production.

Another big supply-side constraint is the cost and availability of labor. The labor force participation rate, which fell drastically during the 2020 lockdowns, has never recovered to pre-pandemic levels. Many older workers took early retirement during/after the lockdowns, with the result that labor is now in relatively short supply. Many firms are struggling to recruit workers even as they increase their wage rates. The result, once again, is that the costs of production have risen and created significant supply-side problems.

Next up, the move towards a more socially oriented style of business conduct, and away from profit maximization, comes at a significant cost. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Social Governance may have the intention of creating a fairer and cleaner society, but it dilutes the key objective of business which is to maximize profit by attaining optimal productivity at the lowest cost.

The term ‘greenflation’ relates to the environmental aspect of this, because green technologies are more costly than traditional technologies e.g., green energy compared to fossil fuels. There may be a solution to this problem in the form of nuclear energy, via molten salt reactors, but the nuclear industry has a terrible publicist. It remains largely underutilized for political, rather than economic, reasons.

Moving on, demographic change is starting to have an impact on society. Half of the baby-boomer generation is now retired and the other will retire over the next 15 years. By that time the first half will have reached nursing home age. The added cost of this, coupled with the low birth rates in the West for many decades, will combine to significantly increase the dependency ratio in the years ahead. The extra costs involved will create a lot of inflationary pressure.

Finally, and following the recent breakdown in relations with China and Russia, there is currently a process underway of ‘reshoring’ industries of strategic importance. Reshoring is the opposite of offshoring i.e., the process of relocating businesses to countries with cheaper costs of production. Reshoring, primarily of manufacturing, will guarantee access to key products in the event of global shortages, and it will have the further advantage of bringing back significant jobs to western countries, but it will come at the cost of higher prices because production costs (especially labor costs) are higher in the west.

The Argument for Inflation 3: Debt, Bailouts & Deficit Spending

Probably the single biggest stand out feature of the western economies at the current time is the eye-watering levels of debt that exist on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. US and UK government debt levels alone rival that which existed after World War 2, but that is just the start of it! Household debt and corporate debt are also sky-high, and the combined magnitude of all this debt is unprecedented in modern history.

Servicing such enormous amounts of debt has become impossible in 2023, because interest rates have risen significantly since March 2022. In light of this, rather than seeking to pay off debts, the US government has abandoned its debt ceiling with the clear intent of running a multi-trillion-dollar budget deficit for the foreseeable future.

The effect of government deficit spending and bank bailouts on the economy is sometimes overlooked. Both of these have the effect of boosting spending in one way or another. Readers may be surprised to learn that ALL hyperinflations are caused not by excessive bank credit, but by excessive government deficit spending, and that mirrors the situation that we are now in.

With regard to consumer debt, the credit-fueled spending frenzy as evidenced by mounting credit-card debt and bank loans, gives an alternative picture of monetary pressures on the price level compared to the argument above that the money-supply is contracting.

Contrary to this view, total bank credit (lending levels) has not been declining recently in any meaningful way. There was a small fall in bank credit following the early March 2023 failures of Silvergate Bank, Signature Bank, and Silicon Valley Bank, but that has stabilized. Certainly, as shown by FRED data (see link below), there is no evidence of any similar decline following the May 1st collapse of First Republic Bank.

What should we expect from consumers once the coming recession starts to bite? They will be faced with losing their jobs, having their hours reduced, and possible negative equity in their homes if they bought recently. No doubt bank credit levels will finally start to show clear evidence of a downtrend by this point, but will consumers be able to pay their existing debts, and will they even want to if their homes are worth less than their mortgages? It would seem likely that a wave of debt defaults is likely.

Similarly, with many zombie firms feeling the pinch, they too could soon be defaulting on their debts. Certainly, the commercial real estate sector is struggling, with low occupancy rates for office blocks due to office-workers moving towards a work-from-home model of employment.

With the government committed to massive amounts of deficit spending, and with a long track record of bailing out the banking sector, it seems likely that the coming wave of private and corporate debt defaults will lead to another massive bailout program.

If this is funded by yet more borrowing, there is a very high likelihood that international investors will soon start refusing to buy western bonds unless much higher interest rates are offered. Western governments’ debt to GDP is typically well above 100%, higher than in Argentina though not as high as in Venezuela, and this is more than enough to create fear of default. Unfortunately, as explained above, if higher rates are offered on new bonds in order to entice investors to buy them, it would likely cause a liquidity crisis.

Alternatively, if budget deficits and bank bailouts are funded via the printing of new money, it can only add huge amounts of fuel to the inflation fire.

Conclusion

The outlook for western economies, with regard to inflation vs deflation in the coming years, strongly favors the former. An inflationary recession looks set to manifest sooner or later. However, it will likely play out differently in different countries.

High costs of production can only be borne for so long before the inevitable happens and either inflation increases, or redundancies/bankruptcies increase, and probably both together. In the meantime, FRED data (see link below) shows that net domestic investment has fallen since 2022, and inflation has soared. It seems that firms are increasingly declining to reinvest in failing businesses in a climate of high inflation combined with an expected economic downturn.

The artificially low interest rates that were pushed for over a decade following the 2008 financial crisis have resulted in enormous malinvestment, with many zombie companies in existence that are unlikely to survive high interest rates for much longer. Once the inevitable happens, and these zombie companies are forced to make cutbacks, the recession that follows will be led by a supply-side contraction. Aggregate demand, on the other hand, will be propped up via yet more deficit spending and bank bailouts. Any interest rate reductions can only mitigate a liquidity crisis temporarily, but cause even higher inflation in the end.

With regard to inflation vs deflation in coming years, it seems unlikely to me that a 15-year ongoing Federal Reserve Bank policy of printing currency like confetti, combined with a similar ongoing policy of massive deficit spending, will all end in deflation.

The US has hiked interest rates higher than most countries over the past year and, in the short-term, the dollar will likely stay relatively strong thereby helping the US to bring inflation down. It's unknown if deflation might briefly occur in the US as the coming recession unfolds, but if so it will still eventually revert back to a high and growing inflation as the the forces described above work themselves out.

The UK, on the other hand, will likely head straight into an inflationary recession. The UK does not have the global reserve currency, and its inflation has been significantly higher than in the US up to now. All of Europe will be hit hard by the coming energy crisis, and oil shortages are a distinct possibility, in which case the costs of production will rise sharply.

The Eurozone countries are already in recession, and Germany in particular looks set for a very deep recession due to its reliance on cheap oil to power its manufacturing base. Sanctions on Russian oil have obviously hit Germany harder than most countries.

Japan has a set of unique challenges and unique characteristics that are hard to predict. It does have by far the highest overall debt, and most of it is government debt. The enormous cost of servicing such debt has led the government to intervene and keep interest rates artificially low, and that does depress the currency while increasing the money-supply, both of which threaten higher inflation. However, Japan also has a relatively thrifty population, huge reserves of US dollar denominated assets, and a relatively good trade balance, all of which better equip it to handle inflationary pressures. Japan is vulnerable to rising oil prices and other input costs though, as it lacks natural resources. Japan also has the most severe demographic problems, with a rapidly aging society.

Time will tell what happens, but the threat of a massive inflationary recession has to be taken more seriously now than ever before.

Sources:

Related Pages: