Galloping Inflation & Hyperinflation

In the post pandemic western world the prospect of galloping inflation emerging in our economies is significantly heightened. Money printing and fiscal stimulus have been excessive in recent years, and global supply lines have also suffered as the negative side effects of 'globalization' have started to be realized.

The question now is what comes next?

On this page I will consider some historical data for the United States and Great Britain to see what lessons can be learned from previous periods of galloping inflation, and the sorts of economic circumstances that allow such an unfortunate state of affairs to arise in the first place.

I will also consider the inflation trends in two countries that have experienced severe hyperinflation in recent decades, and whether or not galloping inflation was a necessary prelude to it.

What is Galloping Inflation?

The term galloping inflation refers to a situation in which prices in an economy are rising at an accelerated rate of at least 10% per year (as measured by the Consumer Price Index), and doing so in a very volatile manner.

Sharp inflation rate rises, followed by equally sharp reductions, along a steep upward trend that may last several years reflects the sort of situation that we are looking at here. Oftentimes it can be a prelude to hyperinflation (i.e. at least 50% inflation per month) unless drastic action is taken to prevent it.

The Jumping Inflation Increase & Decrease Pattern

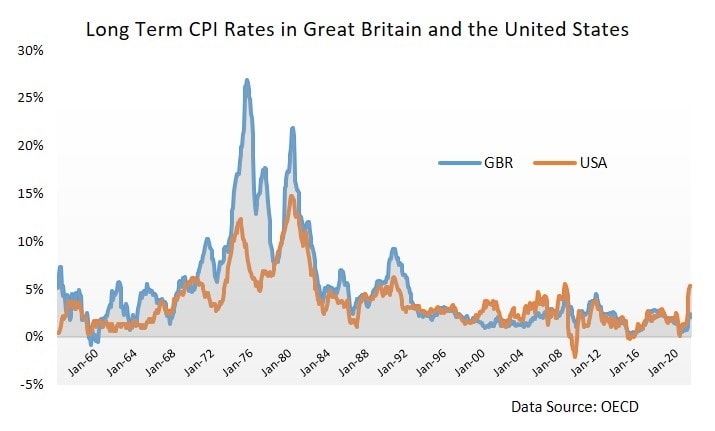

The graph below shows the Consumer Price Index (CPI) for the United States and Great Britain starting from the 1950s. I think that it's fairly clear that something serious happened during the 1970s and well into the 1980s with regard to inflation.

Great Britain in particular saw rising prices of a magnitude that could be mistaken for information relating to Zimbabwe or Venezuela. Peak annual inflation topped 25% in the mid 1970s for Great Britain, and even the US came close to 15%. These are unprecedented rates in modern developed economies and the pattern of sharp rises and falls, indicative of galloping inflation, is quite distinct.

The 1970s was, of course, a very difficult time for business in the developed world in terms of economic output. It was preceded by loose monetary and fiscal policy in the 1960s which, by the 1970s, was already causing some upward pressure on the price level.

Things deteriorated in the early 1970s when the OPEC countries placed an oil embargo on the US and her allies as retaliation for their support of Israel during the Yom Kippur War. The result was a doubling of oil prices, and oil represents a very important component of overall business costs for many goods and services.

In the late 1970s OPEC again doubled the price of oil, meaning a fourfold increase over a period of about 5 years. Both of these actions, combined with rising inflation from the 1960s, led to a period of stagflation, i.e. high inflation and a stagnating economy with growing unemployment problems.

It was not until the early 1980s that the Federal Reserve Bank and other central banks took sufficiently drastic action to curb inflation, with sky-high interest rates reaching around 15% on both sides of the Atlantic. These interest rates did have the desired effect, as illustrated by the declining CPI figures from the mid 1980s onward.

Will a Galloping Inflation rate turn into Hyperinflation?

The lessons of the 1970s make for grim reading, because our current economic predicament shares many similar difficulties with the 1970s. Fiscal policy has been loose for decades, so much so that national debt levels are higher now than they were at the end of World War 2. Similarly, monetary policy has been so loose that interest rates have been close to zero for many years, and still our politicians are pushing for more stimulus.

To be fair, there are some convincing arguments to suggest that the west could be about to enter a deflationary depression rather than a period of higher inflation, and that more stimulus is needed in order to avoid that outcome. However, there are other economists who I find even more convincing, and they point to the ongoing supply-chain problems that are pushing up prices, as well as the fact that there has been an enormous amount of money-printing in recent years.

As Milton Friedman has noted:

"There's been about a 2-year interval between the rapid increase in the quantity of money on the one hand, and the inflationary effects of it on the other."

If his assessment is correct then the years ahead look highly inflationary.

There is a counter argument that points out that whilst the monetary base has grown very substantially in recent times, it is only when the fractional reserve banking system starts lending out that money that we get meaningful money supply growth via the money multiplier effect. So far this has only happened to a limited extent, with banks preferring instead to park their bulging deposits in the Federal Reserve system - a process referred to as reverse-repo growth.

The first leap in inflation is already evident in 2021, as shown in the graph above, whether or not this heralds a coming period of galloping inflation and much higher prices is not yet known.

The most worrying aspect of this is that, if we are headed into a period of high and rising inflation, we are going to need draconian new tools to deal with it. Unlike in the 1970s, we do not have the luxury of low levels of national debt going into this fight, and that means that our ability to tolerate high interest rates is much reduced.

Any attempt to significantly increase interest rates is going to hurt business confidence and reduce investment, causing a serious downturn in the economy. That will increase the government's budget deficit because the taxes it can raise will fall with the economy whilst its welfare bill will simultaneously rise.

The first response to this will no doubt be to try and borrow yet more money to plug the gap in the public finances but, with higher interest rates, the burden of the debt may quickly become too great given its already enormous size.

This of course assumes that there will be lenders prepared to lend more money to us, they may well decide not to do so as it becomes increasingly obvious that our economies are sinking into insolvency.

At that point the only solution will be to print yet more money, and this will further increase inflationary pressures which, sooner or later, will cause rapidly rising prices and a very significant risk of hyperinflation to follow. Something much worse than the high inflation rates we saw in the 1970s may well be on the horizon.

Venezuela Hyperinflation

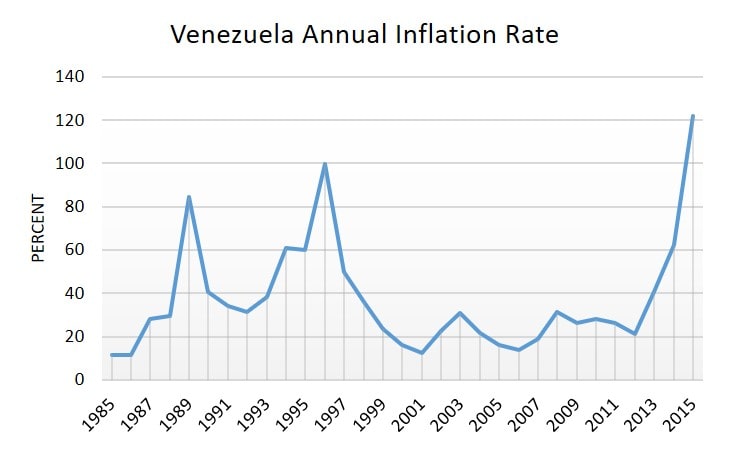

As shown in the diagram below, Venezuela experienced a galloping inflation rate during the 10 years from 1988 to 1998. Whilst the average annual inflation rate over these years was certainly high, ranging from a low of around 31% up to a high of around 100%, there was no emergence of hyperinflation in the years thereafter. The annual inflation rate actually fell to a relatively stable level of around 20% from 2000 to 2012.

Data Source: Statista

Data Source: Statista2013 marked a dramatic change of direction for prices in Venezuela, with inflation climbing continually for 6 years in a row. The graph illustrates the first 3 of these years, with the inflation rate reaching over 120% by 2015. I have not illustrated the years after 2015 because the rate quite literally goes off the chart. The annual inflation rates for the years 2016, 2017, and 2018 are 255%, 438%, and 65,374%. That's not a typo - Venezuela experienced an annual inflation rate of 65,374% in 2018, which clearly constitutes hyperinflation.

Even worse, these are official estimates from the central bank of Venezuela, other sources (including the International Monetary Fund) estimate that inflation actually peaked at around 2,000,000%

Zimbabwe Inflation Rate

If the inflation rate estimates for Zimbabwe are so high that they are incomprehensible, they pale in comparison to the experience of Zimbabwe in 2008.

Data Source: Wikipedia

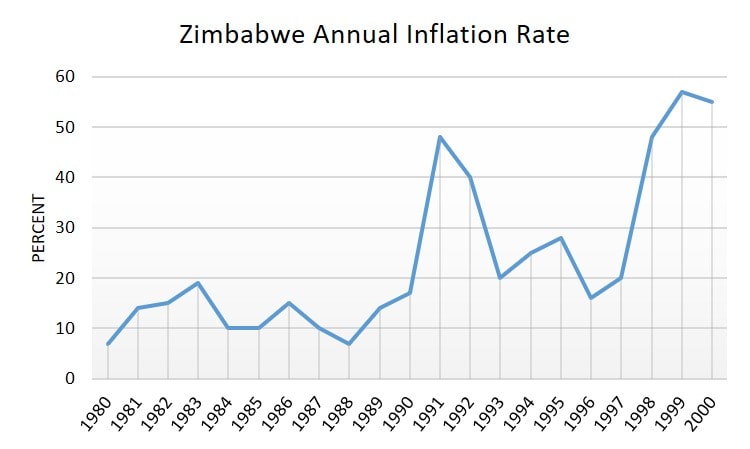

Data Source: WikipediaAs with Venezuela, the years preceding the crisis had been years of high inflation with significant volatility that can be described as galloping inflation. The 1980s had an average annual inflation rate of around 12%, ranging from 7% to 19%. The 1990s were much more volatile with inflation shooting up to 48% in 1991, and then dropping back down to a low of 16% in 1996 before rising again to end the decade at 57%.

The new millennium brought much higher prices, with inflation climbing almost consistently until 2008 (although the official stats show a big dip in 2004). The last available official stats recorded an annual inflation rate of 662,000% - an extreme case of hyperinflation.

Conclusion

The lessons to learn here are both stark and highly instructive, and they need to be taken very seriously. Inflation in the west is already at 40 year highs but, if the typical pattern of galloping inflation leads next to decreases in inflation, then it may encourage some commentators to declare that the situation is resolved when it is nothing of the sort.

There is no reason why the experiences of Venezuela and Zimbabwe cannot be repeated in the developed world if our government elites and our monetary authorities fail to act appropriately. Demand for higher wages is already occurring as inflationary expectations have risen, and this will cause more inflationary pressure in future. Energy and food inflation in particular is apparent, and it is hitting the poor hardest as higher prices erode their purchasing power.

Economic growth will not be able to bail us out of our current predicament (unless a major technological advance such as Nuclear Fusion allows it), and a long awaited correction following the 2008 financial crisis seems imminent because the government will soon be unable to kick the can further down the road.

I don't mean to sound like a harbinger of doom with nothing but bad news, but it does seem like a major economic crisis in the form of much higher inflation, causing much higher prices and collapsing currencies, is looming.

Sources:

Related Pages:

- What is Inflation, and why is it bad?

- Hyperinflation

- Creeping Inflation

- The Bullwhip Effect

- Does Quantitative Easing Cause Inflation?

- Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment

About the Author

Steve Bain is an economics writer and analyst with a BSc in Economics and experience in regional economic development for UK local government agencies. He explains economic theory and policy through clear, accessible writing informed by both academic training and real-world work.

Read Steve’s full bio

Recent Articles

-

Bank Reserves, Asset Inflation, and the Risk of Future Price Inflation

Dec 19, 25 04:16 AM

Learn what bank reserves are, how they affect asset prices, and why future reserve creation could lead to inflation through commodities and currencies. -

Credit Creation Theory; How Money Is Actually Created

Dec 16, 25 03:07 PM

Explore how modern banks create money through credit creation, why the money multiplier fails, and the role of central banks and reserves. -

U.S. Industrial Policy & The Unfortunate Sacrifice that Must be Made

Dec 12, 25 03:03 AM

U.S. Industrial Policy now demands a costly tradeoff, forcing America to rebuild its industry while sacrificing bond values, pensions, and the cost of living. -

The Global Currency Reset and the End of Monetary Illusion

Dec 07, 25 03:48 AM

The global currency reset is coming. Learn why debt, inflation, and history’s warnings point to a looming transformation of the world’s financial system. -

Energy Economics and the Slow Unraveling of the Modern West

Dec 06, 25 05:18 AM

Energy economics is reshaping global power as the West faces decline. Explore how energy, geopolitics, and resource realities drive the unfolding crisis.