- Home

- Circular Flow

- Endogenous Growth Theory

Endogenous Growth Theory & New Growth Theory

Endogenous growth theory was developed by Nobel Prize winning economist Paul Romer in response to the earlier neoclassical economic growth models, partly out of the dissatisfaction Romer had with those models' inability to present a clear link between the saving rate in an economy and its long-term growth rate after a 'steady state' is reached.

For an explanation of those earlier models, see my page:

It's not that the Neoclassical growth models are in error, they just put the emphasis on capital, meaning both physical capital accumulation and human capital accumulation, as the main drivers of long run growth and treat technological progress as a residual element that accounts for remaining growth after capital accumulation has been taken into account.

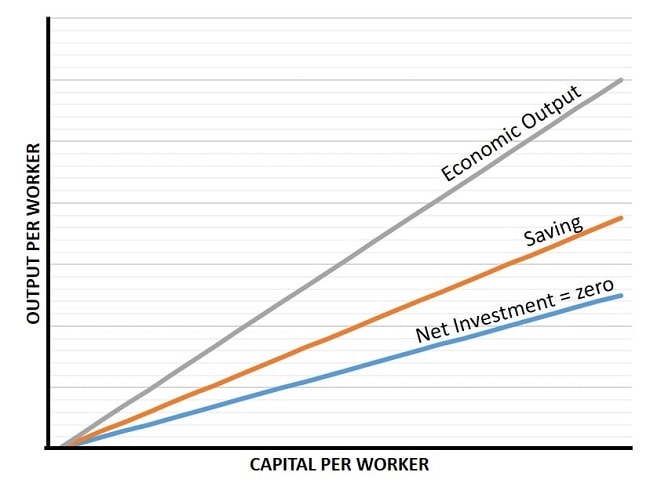

Endogenous Growth Model Graph

The first thing to note about new growth theory is that, unlike the Solow growth model, the saving rate curve and associated economic growth curve are both straight lines. The Net Investment = Zero line is the same in both models and simply illustrates the amount of investment necessary to replace worn out depreciated capital and thereby maintain the existing capital stock.

Since saving is equal to investment in all these growth models (read my National Income Accounting article for an explanation of why this is the case), and is always higher than the rate necessary to maintain the existing capital stock, there is no steady state where capital accumulation settles, and therefore no end to modern economic growth. Higher saving rates simply generate faster development of the economy without end.

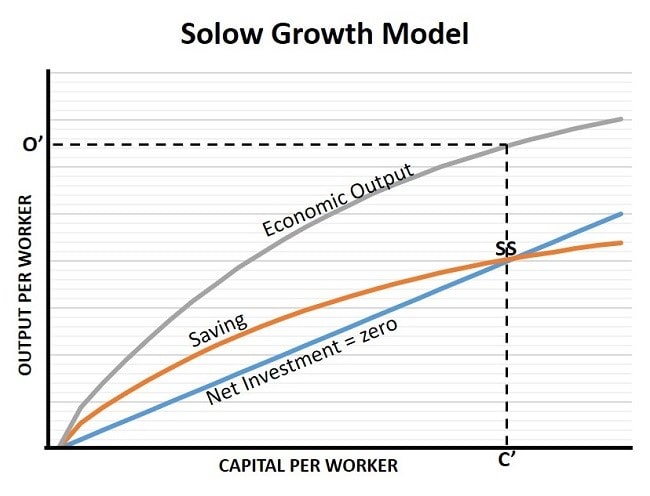

In contrast, consider the Solow growth model where the steady state SS shows a point where saving exactly matches the net investment = zero line, at this point saving is only sufficient to maintain the existing capital stock and so no further economic growth can occur from extra capital per worker. If the saving rate was increased, a new higher saving curve would be drawn and a larger capital stock could be reached, but eventually a new steady state would be reached with no further capital accumulation.

This is the critical difference between the Solow growth model and Endogenous growth theory, which maintains that there is no steady state reached for a given saving rate.

The higher the saving rate, the steeper the straight-line saving curve will be in the top graph above. This implies faster capital accumulation per worker, and therefore higher growth rates (i.e. a steeper straight-line economic growth curve).

Constant Returns to Capital & Growth

The implication of the straight-line saving curve is that an extra unit of capital yields just as much output increase as the previous unit i.e. there are no diminishing returns as in the Solow model. This might appear highly unlikely at first glance, since there is a limit to how much capital a worker can work with at a time, but the growth theory here includes innovation and technical progress within its meaning of 'capital'.

The inclusion of technology and innovation within the definition of capital is what gives rise to the name 'endogenous', which simply means internal to the model. Recall that in the Solow model technological change via improved knowledge and innovation is treated as an external, or residual, driver of growth.

The key distinction here is that with a higher saving rate, part of the resulting higher investment will go towards research & development (R&D), and this will develop new technologies that improve productivity. If the rate of R&D is unrelated to the rate of saving/investment, then the Solow model is a better model of long-term economic growth, but in fully developed economies this seems like an unlikely scenario. R&D is a form of investment in human capital and is therefore funded out of saving.

The question of whether or not the inclusion of R&D (and technological advances) as an endogenous growth driver is limited to producing a constant marginal product of capital is unresolved. It must be at least sufficient to achieve constant returns because anything less than that would imply a bowed saving rate curve as in the Solow model, with a steady state at some point (implying that residual economic growth would be unrelated to saving). This cannot be true when technological advances are included within the model because it would imply that there is some point beyond which further technological advances are either impossible or unrelated to saving/investment.

The possibility of increasing returns to capital arises. This would give us an economic output curve that slopes higher and higher at greater levels of capital per worker.

The Nature of Growth in Reality...

In reality it is likely that the true slope of the saving curve is different at different time periods according to the impact of new knowledge accumulation on productivity, and the rate at which those discoveries can be disseminated to the wider economy.

For example, the industrial revolution led to an explosion of productivity increases in the 19th century, but modern day Japan has experienced very little GDP growth since the 1990s (although that may still be due to ongoing short-term mismanagement rather than long-term factors).

It is impossible to predict the future economics that might cause a new wave of productivity increases, but one possible example might be a breakthrough in the harnessing of nuclear fusion. Nuclear fusion, unlike fission, has the potential to provide abundant, ultra safe, ultra clean, ultra low-cost energy that could really drive huge economic benefits. This is just one example, the potential number of game-changing breakthroughs in economics is limitless.

Challenges to Endogenous Growth Models

There are several challenges and criticisms of endogenous growth models, and I'll deal with the two most significant of them below:

1. Convergence

Some observers argue that if the predictions of the neoclassical, or new growth theory, are correct then all countries with equal population growth and saving rates should converge at equal levels of national income. They then note that many countries show lack of convergence and that the models are therefore wrong.

I would remind the reader that no model in economics is intended to capture all of the endless transitional dynamics between countries, and that this isn't even desirable. The whole point of a model is to simplify concepts in order to make sense of them, and to be able to extract useful information from them.

To argue that the theory is incorrect because there is little evidence of economic convergence between poor countries in Asia/Africa with those in Europe or North America is ludicrous when you consider the other factors involved that are not included in new growth theory. Different cultures yield different attitudes to:

- money lending

- capitalism

- socialism

- female emancipation

- female participation in the workforce

- healthcare provision

- environment

- heritage

- just about everything else

Does the absence of these factors change the fundamental point of the theory? Not if that which is included still yields useful information. In any case, despite the enormous differences across countries, there is indeed significant evidence of convergence once the basic requirements of a functioning economic system are in place e.g. property rights, rule of law, a price mechanism, fair competition, and so on.

2. Investment might not equal savings

The requirement that savings equal investment is built on the exclusion of both government and foreign trade meaning that there is no government spending or taxes and no imports or exports. With those assumptions there is only private sector consumption and savings left, meaning that only savings can fund investment and the two must therefore be equal.

In the real world, once government and foreign trade are included, it is perfectly possible for government to fund some forms of investment e.g. in infrastructure or in education (human capital). Similarly, investment can be funded by foreign firms that wish to open factories and so on within the domestic country. There can even be investment funded via borrowing from overseas.

All this is true, but whilst including these layers of complexity to growth theory might seem to make the science more realistic, none of it changes the end results.

Endogenous Theory & Other New Growth Models

Endogenous growth can be seen as either an alternative or a complement to Neoclassical growth theory.

For less developed economies the Solow growth model may be of more use since it is not necessary for these countries to fund new R&D programs to increase their level of technology - they can can make rapid progress by simply replicating existing technologies from more developed economies.

For advanced countries at the cutting edge of technological know-how, endogenous growth theory may be more appropriate since it better explains the need in these countries for a higher saving rate to fund extra investment in R&D. A higher share of the national income going towards saving and investment would raise the level of technology and achieve higher output rates, and the evidence suggests that the current saving rate is well below the optimum level.

Sources:

Related Pages: