- Home

- Business Cycle

- Decision Lag

Decision Lag in Economic Policy, Explained (with Examples)

The decision lag in economics is the second installment of delayed stabilization policy from the government or monetary authority following some sort of disturbance which has caused the economy to deviate from its long run sustainable growth path (the first being the recognition lag, see the link below for details on that).

The lag time relevant to the delayed effect of interventions varies depending on the nature of the disturbance itself, which (once recognized) may be something that is well understood, or a complete mystery. If the former then the greater understanding of the disturbance will allow a speedy decision to be made about how to deal with it, but if the latter then there may well be a time period of several months for sufficient data to be collected and analyzed before an appropriate policy response can be formulated.

The difficulty associated with the assessment of economic shocks often leads to inappropriate decisions being made, and any active policy always comes with the risk that it will fail in some way. Even successful economic policy interventions will tend to be less than fully successful, and in the worst cases can over-correct in a way that actually causes extra destabilization.

Naturally the different schools of economic science recommend different approaches to managing the economy, with the Keynesians much more likely to favor an active role for discretionary fiscal policy, Monetarists more likely to favor a less active role with a focus on maintaining a stable and slowly expanding money supply, and Austrians prefer to let the free market auto-resolve all but the most severe economic shock.

Inside Lags and Outside Lags

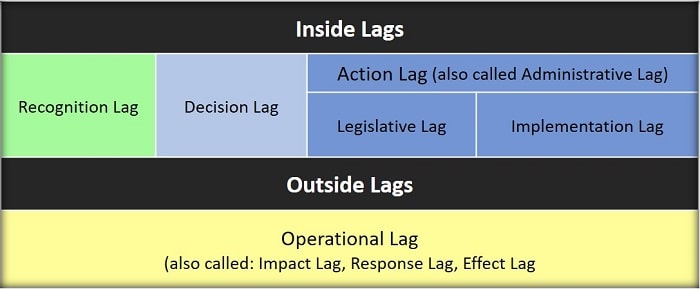

The simple chart below illustrates where the decision lag fits into the broader framework of policy lags related to active stabilization policy:

There is no uniform agreement on this framework, and some other sources might refer to the three types of policy lags, or four types, or five as I've set out here. Less is not always more, so I've opted to divide this particular issue into as many component parts as seem sensible.

You'll also notice that there are many different labels attached to similar concepts, particularly in reference to the outside lag. I've mentioned a selection of them, but you should be aware that I may have overlooked others, so it pays to be aware of the different economic jargon here when studying this area of economics.

Broadly speaking the lags divide into inside and outside types, with inside lags relating to the time taken to get a policy up and running, and outside lags relating to the time it takes that policy to have an actual impact once it is up and running. We should also note that the inside lags further subdivide, with the recognition lag coming first, followed by the decision lag, and then an action lag (or administrative lag) which is subdivided into legislative and implementation components.

For details on the other sorts of lags, see my articles at:

Decision Lag Examples

The best decision lag examples always relate to fiscal policy, as will be explained in the next section, and also come with unanticipated fluctuations in GDP i.e. economic shocks. When fluctuations are anticipated (e.g. the downturn that resulted from the Covid-19 lockdowns), the government is able to make decisions about how best to accommodate them with minimal disruption to the economy.

However, most business-cycles do not come with advanced warnings and are dependent on highly unpredictable factors such as consumer confidence (which affects the consumption component of aggregate demand) business confidence (which affects investment) or supply-side changes to the costs of production (e.g. rising oil & energy costs).

In addition to these factors, the nature of the highly globalized economy in which we all live means that faraway, seemingly unconnected markets, can make a big impact on the global financial system. A collapsing real estate market in China can have a big impact on the solvency of the western banking system if it holds a significant proportion of its reserves in the form of Chinese bonds and securities. The 1997 Asian Financial crisis had a big impact on the global economy, with severe exchange rate fluctuation that caused swings in international trade competitiveness.

All these complicated and interconnected markets require a great deal of expertise to be able to successfully construct appropriate policy responses, and a significant period of time may need to pass before any sort of reliable data trends can be gathered in order to assist policymakers in the decision making process.

Information Lag

Information lag is another type of lag which is highly related to decision lag and arguably forms a sub-category of it. The time taken to make decisions on policy is, in part, determined by the extent of the information lag (i.e. the time taken to gather sufficient information about an economic shock to inform policymakers about what action to take).

However, this does not account for the entire decision making process. There is a strong overlap in time lags here, but the two concepts are not identical.

Fiscal Policy Vs Monetary Policy Lags

As mentioned above, the decision lag that applies to fiscal and monetary policies is quite different.

Monetary Policy Decisions

For monetary policy the lag time is extremely short, and merely requires a meeting of the national monetary authority. These usually occur on a monthly basis but can be convened at short notice in emergency situations.

In the United States the Federal Reserve Bank has a monthly meeting called the 'Federal Open Market Committee' or FOMC. The UK has an equivalent body at the Bank of England called the 'Monetary Policy Committee' or MPC. When these committees meet they will discuss the state of the economy and decide whether or not an adjustment to the existing interest rate (called the Bank Rate) is desirable given current economic indicators and foreseeable developments in the national and global markets.

Fiscal Policy Decisions

For fiscal policy the process is much more drawn out because stabilization policy as a whole takes much longer to get off the mark. The delays are caused not just by the decision lag but also because of legislative and implementation lags relating to drawing up proposals and getting them approved by the senate (or parliament).

Recent evidence of the difficulty here is amply well demonstrated by the inability of the Biden administration to get its 'Build Back Better' program (which included vast amounts of government spending) approved by the senate. Approval was denied because democrat senator Joe Manchin refused to lend his support to the democrat government proposal on account of what he believed to be excessive spending at a time of growing inflationary pressures and excessive national debt.

Due to the delays and difficulties of getting fiscal policy off the ground, short-term economic stabilization has typically fallen to monetary policy. Current circumstances have of course rendered monetary policy somewhat toothless due to the existing liquidity trap problem, but that is a topic for a different article.

The point is that it is usually only the most difficult and prolonged economic shocks that require an active fiscal policy response, and these sorts of problems naturally require a great deal more time for data gathering, analysis, and consideration of alternative responses as part of the decision making process.

Conclusion

The time lags associated with policies aimed at smoothing out the growth path of the economy, whether in the form of countercyclical fiscal policy or monetary policy decisions, make successful interventions very difficult to achieve in practice. Lags in effect may even lead a policy to impact the economy after it has already auto-corrected, in which case it will have a destabilizing effect.

The political pressure on governments to be seen to be doing something may be a more pressing concern than actually doing the right thing, and recent evidence would seem to confirm this given the catastrophic state of the public finances at a time of high inflation.

One lag that is not included in the framework above is the lag between printing money and the inflation that results from it. That lag tends to be around 2-years, and the inflation that we are seeing in 2022 may well be due to inappropriate stabilization policy in previous years.

Sources:

Related Pages:

About the Author

Steve Bain is an economics writer and analyst with a BSc in Economics and experience in regional economic development for UK local government agencies. He explains economic theory and policy through clear, accessible writing informed by both academic training and real-world work.

Read Steve’s full bio

Recent Articles

-

Bank Reserves, Asset Inflation, and the Risk of Future Price Inflation

Dec 19, 25 04:16 AM

Learn what bank reserves are, how they affect asset prices, and why future reserve creation could lead to inflation through commodities and currencies. -

Credit Creation Theory; How Money Is Actually Created

Dec 16, 25 03:07 PM

Explore how modern banks create money through credit creation, why the money multiplier fails, and the role of central banks and reserves. -

U.S. Industrial Policy & The Unfortunate Sacrifice that Must be Made

Dec 12, 25 03:03 AM

U.S. Industrial Policy now demands a costly tradeoff, forcing America to rebuild its industry while sacrificing bond values, pensions, and the cost of living. -

The Global Currency Reset and the End of Monetary Illusion

Dec 07, 25 03:48 AM

The global currency reset is coming. Learn why debt, inflation, and history’s warnings point to a looming transformation of the world’s financial system. -

Energy Economics and the Slow Unraveling of the Modern West

Dec 06, 25 05:18 AM

Energy economics is reshaping global power as the West faces decline. Explore how energy, geopolitics, and resource realities drive the unfolding crisis.