Cost Push Inflation Economics

Cost push inflation occurs when the inputs, and/or raw materials that are used to create goods and services, are rising in price. This makes it more expensive for firms to create those products and thereby forces them to pass on at least some of those extra costs to consumers in the form of rising prices i.e. inflation.

The extent to which firms will be able to pass on the extra costs depends on the nature of the industry in which they operate, and on the 'price elasticity of demand' for the products that they sell. For goods and services that have a high elasticity of demand, any attempt to raise prices will result in a large reduction in quantity demanded, meaning that firms will suffer a large drop in sales and profits.

In these circumstances, the effects of rising input costs are more likely to cause relatively larger increases in unemployment, due to business closures, rather than rising consumer prices. This is best illustrated by a graph.

Cost Push Inflation Graph

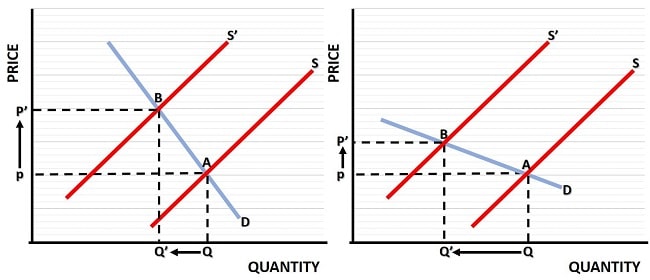

In the Cost Push Inflation Graph below I have illustrated the different effects on price and quantity of output produced for two different elasticities of demand. On the left-side of the graph, the price elasticity of demand is low, and on the right side it is high.

As you can see, when the elasticity of demand for a product is low, its demand curve will be steeper and any contraction in supply resulting from higher costs of production will lead to a relatively high increase in consumer prices and relatively lower reduction in production quantity. The prices will be more readily absorbed without so much need for cutbacks in production because consumers have a greater need for these types of goods.

Cost push inflation will be more pronounced for these products, but there will be fewer job losses, at least within the industry.

On the other hand, when the price elasticity of demand is higher, firms will be forced to cut production to a higher degree because consumers will not accept high price increases. In these industries, with much reduced production levels, job losses will be higher.

The industries where prices will rise the fastest are those which produce basic necessities. Food and energy are the most obvious examples, and for this reason the government's preferred measure of the costs of living, the Consumer Price Index (CPI), excludes food and energy from its calculations.

That might seem like the government is rigging the numbers, and many economists believe that the numbers are indeed artificially handled so as to under-report true inflation. However, it is fair to recognize that food and energy prices are much more volatile than other prices, and that it is perhaps better for a cost of living index to report changes in more stable prices. The CPI Core Inflation numbers do that.

Cost Push Inflation Causes

Cost push inflation is caused by increased costs of production, and most typically this comes down to an increase in the cost of oil. Oil accounts for a large component of production costs for many industries, because it remains an irreplaceable fuel.

This being the case, government policy relating to fossil fuels and carbon emissions is an important driver of industry costs. I won't get into the arguments for and against climate change, but the economics are clear, at least in relation to energy costs in the near term.

Any policy that seeks to restrict oil use (e.g., by higher taxes, withdrawal of drilling permits, sanctions on other oil-producing countries, and so on) will cause higher oil prices which will inevitably cause supply-side problems leading to cost push inflation.

The list of raw materials and component parts used in industry is long, and many of them have the potential to cause significant cost increases if they become difficult to obtain:

- A lack of semiconductors in 2021 caused a halt to the production of new cars, with the result that second hand car prices rose sharply.

- Soil erosion and lack of fertilizer is likely to cause agricultural prices to rise in the years ahead.

Labor is the other main cost of production that can lead to cost push inflation. The idea here is that excessive wage demands might cause production costs to rise, but the evidence shows that wage demands tend to be more reactive to existing inflation rather than being a cause of that inflation. In other words, higher wage demands usually come as a response to higher costs of living, but something else causes the higher costs of living in the first place.

Effects of Cost Push Inflation

The effects of cost push inflation on the economy are often more serious than demand push inflation, and the reason for this is because it is much harder to reduce it without a significant contraction of the economy, with much more business closures and unemployment as a result.

In the graph above I have illustrated a contraction of the aggregate supply curve from AS to AS'. This shift results from the effects of cost push inflation because, at each price level, firms are only willing to supply a smaller quantity of output.

A new equilibrium point in the economy will emerge at the intersection of AS' and AD with a higher price level of P' and lower economic output level of Q'. A new and higher long-term level of structural unemployment will also emerge that reflects the new higher costs of production.

Now, if the government intervenes and attempts to increase aggregate demand from AD to AD' in order to pull the economy back to its previous output level, and thereby reduce unemployment back to its previous level, this will have the effect of pulling prices even higher and creating a self-fulfilling upward spiral in prices that will be very difficult to stop.

Given the effects of cost push inflation, any demand management policy to stimulate the economy will be unsustainable, and will only create spiraling inflation in future. This process is explained in my article about the:

Unfortunately, in order to control inflation and stop it from permanently rising to a new level, there may need to be a period of even higher unemployment by actually reducing, rather than stimulating, aggregate demand. This is to prevent inflationary expectations from rising, because this will again become a self-fulfilling prophecy that leads to permanently higher inflation. For further explanation of this, refer to my article at:

Related Pages: