Complementary

Goods & Substitute Goods Explained (with Examples)

Complementary goods are products that are consumed or used together. When the demand for one good increases, it leads to an increase in the demand for its complementary counterpart. The classic example of complementary goods is peanut butter and jelly. When people buy peanut butter, they often purchase jelly as well, as the two products are commonly used together in sandwiches.

Substitute goods, on the other hand, are products that can be used interchangeably to satisfy a similar need. When the price of one substitute good increases, consumers tend to switch to a more affordable option. An example of substitute goods is butter and margarine. Both products serve the same purpose of spreading on bread or cooking, so when the price of butter rises, consumers may opt for margarine as a cheaper alternative.

Examples

of Complementary Goods

Complementary goods refer to products that are consumed or used together, enhancing the marginal utility that each good provides. The demand for one good is directly related to the demand for the other. When the price or availability of one complementary good changes, it can significantly impact the demand for the other. Here are four examples:

- Peanut butter and jelly – Often bought and consumed together, a change in the price of one affects the demand for the other.

- Printers and printer ink cartridges – As printer prices decline, the demand for printers increases, leading to a higher demand for ink cartridges.

- Gaming consoles and video games – A new gaming console's release increases the demand for compatible video games to enjoy the full gaming experience.

- Hot dogs and hot dog buns – The number of hot dog buns sold is closely related to the number of hot dogs, as people usually buy them together.

Examples

of Substitute Goods

Substitute goods are products that can be used in place of one another. If the price of one substitute good rises, the demand for that good may decrease, and consumers may opt for the alternative product instead. Here are four examples:

- Tea and coffee – If the price of coffee rises significantly, consumers may switch to tea as a more affordable alternative.

- Butter and margarine – When the price of butter goes up, some consumers may choose to buy margarine instead.

- Air travel and train travel – If airfare becomes too expensive, people may opt for trains for shorter distances, leading to an increase in the demand for train tickets.

- Brand name drugs and generic drugs – Consumers may choose to buy generic versions of medications if brand name drugs are expensive.

Perfect

Complements and Perfect Substitutes

The shape of an indifference curve gives us information about whether or not two goods are substitutes or complements, and at the extremes, when we look at perfect complements and perfect substitutes, these curves are unique.

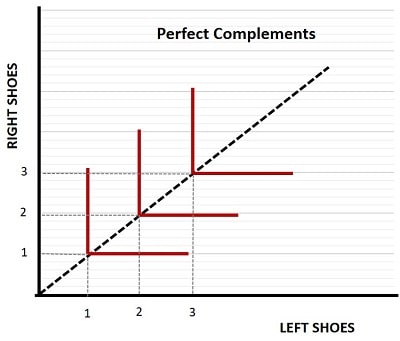

For perfect complements an indifference curve is L-shaped, and while rare we can imagine how this might be the case with shoes for left feet compared to right feet. As a refresher, each indifference curve is drawn for a given level of utility i.e. consumer satisfaction. In the graph above, with 1 left shoe and one right shoe, a higher indifference curve can only be reached with an increase in both left and right shoes, simply increasing one or the other yields no extra utility.

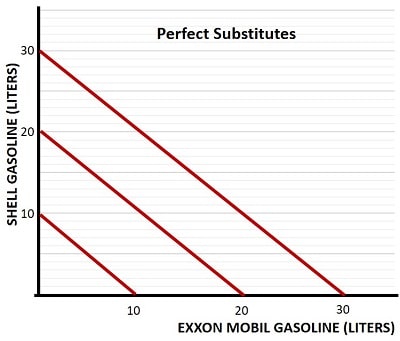

With perfect substitutes the indifference curve is a straight line, meaning that there is no diminishing utility from increasing more of one good and decreasing an equal amount of the other. For example, if a consumer has equal access to Shell gasoline and Exxon Mobil gasoline, he/she will be completely indifferent about using only Shell or only Exxon, or any combination of the two.

Either option yields just as much mileage for the consumer's car, and causes no greater or lesser wear and tear on the car, so these two types of gasoline are perfect substitutes.

For regular non-perfect substitutes and complements, indifference curves are bowed. The more bowed they are, the more that they are complements, and the less bowed, the more that they are substitutes.

The

Importance of Understanding Substitute and Complementary Goods

For businesses, comprehending the relationship between substitute and complementary goods is pivotal in devising pricing and marketing strategies. They must consider the impact of changes in one product's demand on its complement or substitute to stay competitive in the market.

Additionally, businesses can create product bundles to promote complementary goods. Offering discounts on printer purchases while charging regular prices for ink cartridges could incentivize consumers to buy the package rather than opting for separate items.

Understanding these concepts also helps governments and policymakers analyze market behavior and formulate effective economic policies. Antitrust regulations, for instance, may come into play when investigating companies that dominate the markets of both complementary and substitute goods, potentially leading to monopolistic practices.

For consumers, knowledge of these goods can lead to more cost-effective choices. For example, if they are aware of substitute goods, they can make smart decisions when prices fluctuate, ensuring that they get the best value for their money.

The

concept of cross-price elasticity

To understand the relationship between complementary and substitute goods, we need to first understand the concept of cross-price elasticity. Cross-price elasticity measures the responsiveness of the demand for one good to a change in the price of another good.

For complementary goods, the cross-price elasticity is positive because an increase in the price of one good leads to an increase in the demand for its complementary counterpart. On the other hand, for substitute goods, the cross-price elasticity is negative because an increase in the price of one substitute good leads to a decrease in the demand for the other substitute good.

Cross-price elasticity helps economists and businesses analyze the impact of price changes on consumer behavior and adjust their strategies accordingly.

Conclusion

Complementary and substitute goods are fundamental concepts in economics that shed light on the complex relationship between different products and consumer choices. Complementary goods work in harmony, enhancing each other's utility, while substitute goods provide alternatives that can be interchanged based on price and availability.

The cross-price elasticity of demand, which ranges from 0 to 1, is the tool used by economists to estimate the sensitivity of one good’s price & demand to another good. For perfect substitutes the elasticity is 1, for perfect complements it is 0.

By understanding market dynamics, businesses can devise effective strategies to maximize sales and profit, while consumers can make informed decisions to maximize utility in the face of changing market conditions. Substitute and complementary goods are not merely theoretical ideas; they are the building blocks that shape the modern marketplace, influencing our daily choices and driving economic progress.

Sources:

Related Pages: