- Home

- Market Failure

- Coase Theorem

The Coase Theorem Explained (with an example)

The Coase Theorem is a principle in economics, developed by British Nobel Prize winning economist Ronald Coase. It provides a powerful theoretical framework for understanding how private actors can resolve the issue of externalities if certain conditions are met.

Coase's theorem has far-reaching implications for how societies think about pollution, environmental regulation, and other forms of externalities in the modern economy.

In this article I will break down the Coase Theorem, focusing on its relationship with property rights, externalities, bargaining, and economic efficiency.

Understanding Externalities - The Starting Point

The Coase Theorem relates to the concept of ‘externalities’ in economics i.e., costs or benefits that affect third parties (people other than the buyer or seller) in a transaction.

An externality occurs when a third party is affected by the economic activities of others without compensation. These affects can be either negative or positive depending on the circumstances. For more details about this, see my main article at:

Externalities represent a form of market failure, where individual decisions lead to socially inefficient outcomes because the full social cost or benefit is not taken into account by the decision-makers.

Traditionally, governments intervene in these situations with regulations or taxes to correct the inefficiency. However, Ronald Coase challenged the notion that state intervention is always necessary. He argues that, in many cases, private parties can resolve these externalities themselves through negotiation provided that certain conditions are met.

The Role of Property Rights

Property rights are at the core of the Coase Theorem. These rights must be well-defined and enforceable for private bargaining to resolve externalities efficiently. Property rights refer to the legal ownership or legal entitlement to use and control a particular resource, be it land, air, water, or other tangible and intangible assets.

In Coase’s world, the allocation of property rights determines the starting point of negotiations. The Coase Theorem argues that, regardless of who is initially assigned these rights, private parties can bargain their way to an economically efficient outcome. What matters is that the rights are clearly defined, and the parties involved have the ability to negotiate without significant barriers.

For example, imagine a negative externality arising from a factory that emits pollution affecting nearby residents. If the residents have a right to clean air, they could demand the factory reduce its emissions or compensate them for the pollution.

On the other hand, if the factory has the legal right to pollute, the residents might offer to pay the factory to reduce its pollution levels. Who holds the rights initially does not affect the final outcome as long as the conditions of the Coase Theorem hold - the efficient level of pollution reduction will be reached regardless.

The Bargaining Process

Bargaining is the mechanism through which externalities can be internalized according to the Coase Theorem. Private parties can negotiate to arrive at a mutually beneficial solution, effectively transforming external costs or benefits into explicit payments or concessions. As long as the transaction costs (i.e. the costs associated with making, enforcing, or monitoring a deal) are low or zero, this negotiation will lead to an efficient outcome.

An example of a Coase Theorem bargaining opportunity.

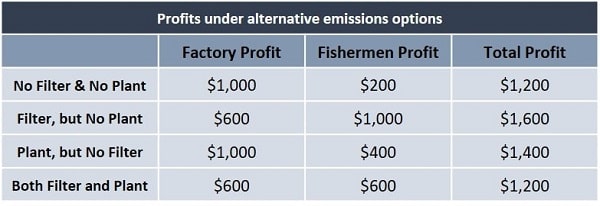

An example of a Coase Theorem bargaining opportunity.The table above sets out an example of how private sector bargaining can lead to an efficient outcome without any need for government involvement.

Continuing with the manufacturing firm that causes pollutants to enter a local river as a byproduct of its operations, we assume that the firm has a clear right to pollute, but that it is open to negotiate with other users of the river regarding its emissions.

The table sets out four alternative options for the firm and some local fisherman that want a cleaner river. There are two cleanup methods:

- The use of a filter by the manufacturing firm.

- The operation of a treatment plant by the fishermen.

The first option is the status quo with neither filter nor treatment plant, but this option is unlikely since the fishermen can do better by operating a treatment plant. This is shown by the third option, with the fishermen making $400 profits instead of $200.

The fishermen would do even better if they could convince the manufacturing firm to use a filter, in which case the fishermen would opt against the treatment plant and make $1,000 profit (option 2). Maintaining the treatment plant when a filter is being used (option 4) makes no sense since it costs the fishermen more than it makes as evidenced by the smaller profit of $600 vs $1,000.

Unfortunately for the fishermen, the use of a filter would cost the manufacturing by reducing its profit from $1,000 to $600. Without a filter, the most profit the fishermen can make is $400 (option 3), but with a filter they can make $1,000 (option 2), so the fishermen will be prepared to pay the manufacturer upto $600 to install a filter.

The cost of a filter is only $400 in lost profit to the manufacturing firm, so it will happily accept offers over $400 from the fishermen to install the filter. Option 2 is therefore the most likely outcome following negotiations between the manufacturer and the fishermen.

The fishermen will pay the manufacturing firm somewhere between $400 and $600 to install the filter. The actual amount agreed will depend on the bargaining power of the fishermen vs the manufacturer, but so long as a figure is agreed economic efficiency will be optimized with option 2 being chosen and total profit maximized at $1,600.

It’s important to note that while the Coase Theorem emphasizes efficiency, it does not address the distribution of wealth or fairness. The outcome will be efficient, but the distribution of benefits and costs may be unequal.

For example, if wealthier parties hold the property rights, they may extract more favorable outcomes in negotiations. In the example above the manufacturing firm might be able to pressure the fishermen into paying closer to $600 for the filter, rather than the $400 that would cover their cost.

This has led to criticism of the Coase Theorem, particularly from those concerned with equity and social justice.

Transaction Costs

With the Coase Theorem hinging on the idea that transaction costs are low or nonexistent, problems arise when this is not the case. These costs include legal fees, bargaining costs, enforcement costs, and the costs of gathering information. In reality, high transaction costs can impede an efficient bargaining process.

If there are multiple parties involved (such as hundreds of residents affected by pollution), or if the legal and administrative process is complex, these costs may prevent parties from reaching an efficient solution. In such cases, the market alone may not be able to resolve the externality problem, and government intervention could be necessary.

Efficiency and the Coase Theorem

Efficiency in economics means that resources are utilized in a way that maximizes current and future production, and also allocates goods in a way that optimizes tho total amount of utility for consumers. The Coase Theorem has little to do with the allocation of goods to consumers, but it does relate to productive efficiency.

The Coase Theorem argues that when property rights are clearly defined, and when the costs of enforcing agreements are low, private negotiations will lead to the efficient allocation of resources. This results in an internalization of externalities, where the parties directly involved account for the costs or benefits their actions impose on others.

Conclusion and Real-World Implications

While the Coase Theorem provides a powerful theoretical insight, its real-world application is often limited by high transaction costs, poorly defined property rights, and collective action problems. In practice, the following factors often complicate the Coasean bargaining process:

- Public Goods and Collective Action - When many people are affected by an externality (e.g., air pollution affecting a city), coordinating negotiations between all parties is nearly impossible. The "free-rider problem" also arises when individuals benefit from others' negotiations without contributing themselves.

- Legal and Institutional Frameworks - Clear and enforceable property rights are often absent or contested, especially when it comes to common resources like air and water. Defining these rights can be costly and politically contentious.

- High Transaction Costs - In many cases, the costs of negotiation, legal enforcement, or organizing multiple stakeholders are prohibitively high, making private bargaining impractical.

The Coase Theorem offers a compelling theoretical solution to the problem of externalities by focusing on the role of property rights and private bargaining in achieving economic efficiency. It suggests that private parties can often negotiate to internalize externalities, solving market failures and making government intervention unnecessary.

Related Pages:

- Socially Optimal Quantity

- Pigouvian Subsidy

- Corrective Tax

- Tradable Pollution Permits

- Public Goods

- Marginal Social Cost

- Marginal Social Benefit

- Economic Efficiency

- Externalities

- Market Failure

About the Author

Steve Bain is an economics writer and analyst with a BSc in Economics and experience in regional economic development for UK local government agencies. He explains economic theory and policy through clear, accessible writing informed by both academic training and real-world work.

Read Steve’s full bio

Recent Articles

-

Bank Reserves, Asset Inflation, and the Risk of Future Price Inflation

Dec 19, 25 04:16 AM

Learn what bank reserves are, how they affect asset prices, and why future reserve creation could lead to inflation through commodities and currencies. -

Credit Creation Theory; How Money Is Actually Created

Dec 16, 25 03:07 PM

Explore how modern banks create money through credit creation, why the money multiplier fails, and the role of central banks and reserves. -

U.S. Industrial Policy & The Unfortunate Sacrifice that Must be Made

Dec 12, 25 03:03 AM

U.S. Industrial Policy now demands a costly tradeoff, forcing America to rebuild its industry while sacrificing bond values, pensions, and the cost of living. -

The Global Currency Reset and the End of Monetary Illusion

Dec 07, 25 03:48 AM

The global currency reset is coming. Learn why debt, inflation, and history’s warnings point to a looming transformation of the world’s financial system. -

Energy Economics and the Slow Unraveling of the Modern West

Dec 06, 25 05:18 AM

Energy economics is reshaping global power as the West faces decline. Explore how energy, geopolitics, and resource realities drive the unfolding crisis.