- Home

- Supply-Side

- Aggregate Supply

The Aggregate Supply Curve

Aggregate supply is a concept that is used to describe the total amount of goods and services that can be produced over a given period of time, and subsequent periods typically have small expansions of aggregate supply due to continuous economic growth from cumulative small technological advances.

The classic example of a large aggregate supply shift occurred in the 1970s when the price of oil, a major factor in the costs of producing a vast number of goods & services, quadrupled. Shifts of this sort are particularly disruptive to an economy because they entail both lower output levels, i.e. higher unemployment, and higher price levels which can develop into ongoing inflation.

A good study of aggregate supply is timely amidst the economic carnage of the COVID-19 pandemic that has swept the globe and led to wholesale lock-downs of many major industries.

Speculation about higher inflation rates in the near future is mounting, particularly since the cuts to supply have typically been accompanied with fiscal stimulus in the form of welfare payments and yet more rounds of quantitative easing - all of which boost aggregate demand at a time when aggregate supply is being restrained. Time will tell what happens, but the omens are not good.

Aggregate Supply Graph

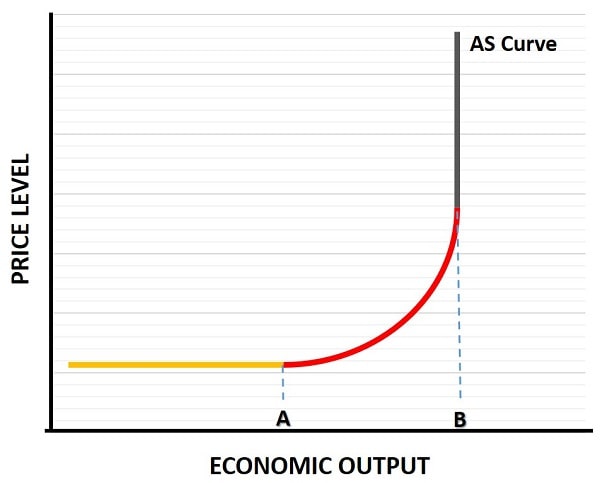

As can be seen from the aggregate supply graph, there are three distinct sections of the aggregate supply curve with regard to its relationship with the price level.

The first section, in yellow, is completely flat meaning that at any starting level of economic output, and increase in output can be had without any impact on prices.

The middle section, in red, shows that for any increase in economic output beyond point A, there will be an increasingly large impact on prices.

The final section illustrated, in grey, shows that once the economy reaches an output level at point B, any further push for higher output is futile and only leads to higher prices.

Short-run aggregate supply

One way of thinking about the different sections of the aggregate supply curve is to relate it to a particular time-frame. The short rum aggregate supply curve, also known as the Keynesian aggregate supply curve, constitutes the yellow horizontal section of the curve in the graph above.

This is the part of the curve that reflects spare capacity in the economy such that there are underutilized factors of production that can be brought into use via a stimulus package. The point is that firms can increase production at existing prices because of the spare capacity.

Technically speaking it is not entirely true that there are no price level increases with a Keynesian aggregate supply curve, because there is usually some inflation even when there is spare capacity in an economy. But these price level movements occur via upward shifts of the curve over time due to the impact of inflationary expectations (see my page about the NAIRU for details on this).

Long-run aggregate supply

The long-run aggregate supply curve, also known as the classical aggregate supply curve, is depicted by the vertical grey section of the curve in the graph above. As you can see, on this section of the curve the price level is the only thing that moves when the government tries to stimulate the economy.

The point here is that all resources are being fully utilized at the sustainable level. This does not mean that there is no ability to temporarily boost economic output, only that any temporary boost cannot be sustained and will simply result in a higher price level, and a higher inflation rate if it causes inflationary expectations to rise.

Over time, as the economy grows due to technical advances, the long-run aggregate supply curve shifts to the right.

For simplicity in the analysis models, we tend to hold technology constant in the classical model, just as we hold inflationary expectations at zero in the Keynesian model.

The middle ground

In reality, the relevant part of the aggregate supply curve is the middle, upward sloping, portion of the curve that sits in between the Keynesian and classical extremes. There are, of course, times when the relevant part of the curve is closer to one extreme or another, and this is usually the cause of debate among economists regarding the appropriate policy mix, because there's no way to know exactly where on the curve the economy sits at any point in time.

All economic data is published with a significant time lag, and any active policy formed on the basis of that information will incur a further lag before it takes effect. So the problem is not so much about knowing where on the curve the economy sits, but rather where it will sit at the time a policy action takes effect.

As you can imagine, this is a very difficult thing to get right, and many economists prefer a hands-off approach to demand management in all but extreme circumstances. The Keynesian school does, as you would expect, tend to prefer more policy action than economists of alternative schools of thought.

Affects of Fiscal & Monetary Policies

The affects of different stimulus policies can come with different side-effects depending on the type of policy that the government pursues, but it depends on which part of the AS curve is relevant at the time of the policy implementation.

In the short-run Keynesian case, the effects of both fiscal policy expansion and monetary policy expansion are much the same and just produce a boost to aggregate demand which increases economic output without any impact on the price level.

Things are a little more complicated in the classical long-run case.

Fiscal policy with classical aggregate supply

In the classical model, a fiscal expansion such as an increase in government spending or a tax cut, would result in a new aggregate demand curve that intersects aggregate supply at a higher level. Since the supply curve is vertical in the classical long run model, all that results from the extra demand is a higher price level.

Strict adherents of the model insist that even in the short-run there can be no temporary unsustainable increases in output, but this is highly debatable.

For now we simply take the model at face value and recognize that it predicts no change in output and only higher prices as a result of fiscal expansion.

The important implication here is that, after an increase in government spending, that spending must have come at the expense of some other spending i.e. private sector spending. This is a process known as 'crowding out', and in the classical model it is complete. In other words, every penny of extra government spending results in an equal amount of reduced private sector spending.

Monetary policy with classical aggregate supply

An attempt to increase economic output via expansionary monetary policy in a classical aggregate supply model is easy to refute. To see this, imagine that the government increases the money supply. This will lead to a higher aggregate demand curve just as with a fiscal boost, and just as before the only effect is to increase prices.

Now, as prices increase the purchasing power of the money supply decreases. This decrease in purchasing power will continue until the increased money supply has the same purchasing power as the initial money supply.

So, all that has happened is that the increased money supply was eroded in value until it equaled the purchasing power of the original money supply. The aggregate demand increase was effectively decreased back to its original curve.

Criticisms

I've kept controversy out of the conceptual analysis above, because no one really disagrees with the concepts. Where there is disagreement relates on the practical application of economic policy based on the concepts discussed.

Aggregate Supply shifts can happen

You should keep in mind that the AD-AS model was developed with the assumption that aggregate supply is usually very stable. From this assumption the New-Keynesian economists tend to analyse too many contractions as being in need of stimulus.

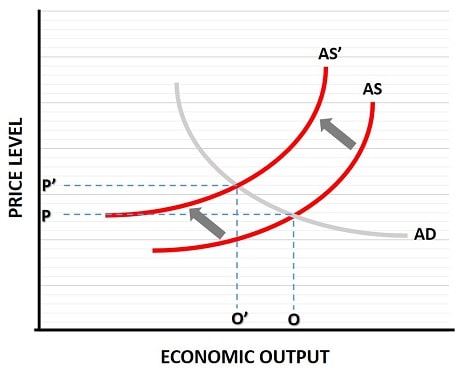

In the diagram you can see that when supply does contract (as in the 1970s when oil prices quadrupled, and as with the current COVID-19 pandemic that has shut down huge sections of our economies and compromised global supply chains), the result leads to both decreases in economic output (and therefore more unemployment) as well as a higher price level (that may lead to persistent inflation).

If the government were to push for a stimulus package under these circumstances (as they unanimously are throughout the western world) then the predicted result is an even higher price level as output is boosted, and this can create a serious threat of very high inflation that quickly gets out of control.

Deeper analysis is often overlooked

Whilst we may all observe a movement in prices and economic output, there is a great deal of disagreement about what the causes of that movement were, and what the long-term consequences of it are.

Additionally, even if the unthinkable occurred and every economist agreed about the causes & consequences of a movement, there will still be huge disagreement about the correct course of corrective action and the overall size and relative balance of corrective stimulus packages, i.e. the correct balance of fiscal and monetary actions.

Furthermore, it may be that the correct course of action is to do nothing at all. History has provided a great deal of evidence that corrective economic policies can actually be destabilizing rather than corrective, because of all the time lags involved in observing a problem, implementing a solution, and the solution taking effect make corrective policies virtually impossible to calculate in most cases.

Finally, what if a decline in output is a good thing - this possibility is never considered. It is perfectly possible that a decline is desirable if the economy had been overheating prior to that decline. But even if there was no overheating, a decline may have resulted simply because consumers have an increased desire to save more of their earnings.

Whilst an increase in the rate of saving would come with some initial extra unemployment (because output levels depend more on spending rather than saving), it would also imply a higher investment rate, more growth, and ultimately a higher level of economic output i.e. an expansion of the entire aggregate supply curve.

In summary, observing and understanding the concepts behind the aggregate supply model is not controversial, but drawing practical conclusions from it is a different matter, and more often than not leads to strong disagreement.

My personal preference, as usual, is to side with the Austrian school of economics and take a hands-off approach to these things rather than trusting the incompetent hand of government to put together a helpful policy response. I do, however, believe that an enhanced set of automatic stabilizers in the economy are desirable, and that both a stable banking system as well as sensible supply-side economic policies would complement a hands-off approach to fiscal/monetary stimulus.

Related Pages: