What is Demand Destruction in Economics?

Demand destruction in economics is a relatively new term that has been coined by economists to describe a process by which, it is hoped, reduced inflation will result. The theory here is nothing new, but quite dubious when applied at the level of an entire economy.

The process works well when the price of a specific product is persistently high, thereby resulting in a permanent downward shift in demand for it from consumers as they begin to substitute cheaper alternatives instead. The theory is much more applicable when applied to a single product, or set of products, but when all products are rising in price due to high inflation then the substitution process is somewhat handicapped.

The availability of cheaper alternatives allows a gradual shift in demand away from the expensive items towards the more competitive alternatives. However, when inflation is high it tends to make all products rise in price, and cheaper alternatives less likely to exist.

The process is not entirely disabled through high inflation, because substitution will still occur even when all prices are rising. For example, if fillet steak (an expensive food item) is rising in price at the same time that the price of ground beef (a cheaper alternative) is rising, consumers will still be able to make significant cost savings by switching from steak to ground beef.

In this article I will consider the circumstances in which demand destruction is good or bad for the economy.

Is Demand Destruction Good or Bad?

When Demand Destruction is Good

The nature of price changes and the 'price mechanism' in free-market economics is one of the key indicators for economic agents to adjust their consumption and production behaviors. Without the freedom for prices to adjust as market circumstances require, the efficient functioning of markets would be impossible.

The forces of supply and demand interact to determine the market clearing price, a price at which consumers' demand for a product matches producers' supply. Any deviation away from that price will result in either excess demand or excess supply, with overall losses for society.

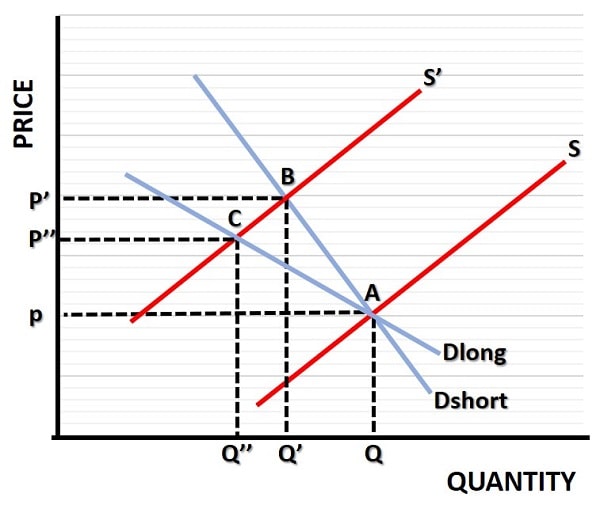

With demand destruction, the analysis is a little more nuanced in that we take a more long-term view of what happens. In the short-term, the market response to a higher price will lead to fewer sales, but in the long-term that reduction in sales will be more significant because demand is more 'price elastic' in the long term.

In the demand destruction graph above, the initial reaction in the market to a contraction in supply leads to a shift in the equilibrium from point A to point B. Price rises from P to P' and quantity falls from Q to Q'. As time passes, the higher price leads to permanent demand destruction as consumers substitute cheaper alternatives. As this happens, quantity falls even more to Q'', and the price rise reverses somewhat to P''.

For example, a rising price of oil and gas may initially cause consumers to economize on their travel needs, thereby reducing their consumption of gasoline, but only in the long-run (when they consider that gas prices are permanently higher) will they be more likely to change their cars to more fuel efficient alternatives. All of this is part of the healthy and efficient functioning of markets.

When Demand Destruction is Bad

The problems with demand destruction relate more to the effects of inflation and the boom-bust business cycle at the level of the entire economy.

When an economy is poorly managed, and consumption is allowed to accelerate at a faster rate than production growth can accommodate, inflationary pressure will build up and, sooner or later, something will break. When that happens a recession will result and unemployment will rise.

These cycles are, in the opinion of Austrian economists, a natural weakness of our current fiat monetary system with Federal Reserve Bank control over interest rate policy. Why is this - it is because the interest rate is the price of money, and when you take away from the market the power to set prices, you invariably end up with the wrong prices.

Interest rates in the western world had been artificially low for many years after the 2008-09 financial crisis, and it led to massive excess demand for money via borrowing. Government debt, corporate debt, and household debt all rose dramatically post 2009, and when the initial price rises in bonds, equities, and real estate started to feed into a general rise in the price level (as measured by the CPI), it was clear that the economy had overheated.

The belated response by the Federal Reserve Bank to raise interest rates, in order to curb inflation via general demand destruction at the aggregate level, will likely cause a massive recession in the near future.

Naturally, this is not a good thing. It represents yet another example of the futility of trusting the political elites to competently manage the economy. The price of money (the interest rate) is the single most important price in the economy, and when politicians or politically appointed officials control it then the problems of excess demand and supply will inevitably follow.

Final Thoughts

Demand destruction can mean different things to different commentators. Traditionally the term was used more or less exclusively in the microeconomics context of a single product, where the long-term effects of an increased price led to a significant substitution of cheaper alternative products.

More recently, demand destruction at the aggregate level, via interest rate rises aimed at controlling inflation, has started to receive some attention. This is, of course, a quite different phenomenon and the use of the same term to describe two different things does nothing to clear up the level of confusion in economic science.

In the traditional sense, where free markets are allowed to adjust to changing circumstances, demand destruction is a good thing. In the more recent sense, where aggregate demand destruction is sought by the monetary authorities as a means of mitigating previous policy errors (that have allowed inflation to soar out of control), it may or may not be a necessary evil but it is clearly not good.

The consequences are likely to cause a sharp rise in cyclical unemployment as well as a severe recession. The response to that might then be to reflate the economy, and that comes with its own problems as discussed in my article about reflation.

Related Pages:

- How to Stop Inflation

- What Causes Inflation?

- Rent & Price Controls

- What is Inflation, and why is it Bad?