- Home

- Monetary Policy

- Velocity of Money

The Income Velocity of Money

As an introduction to the concept of ‘velocity of money’ I should start by clarifying that in this article I am referring to the income velocity of money rather than the transactions velocity. There are some technical differences, but there is no difference in conceptual meaning or policy implications.

For anyone who needs to dig into the weeds, the PDF link at the bottom of the page includes details on the technical differences between the two. As a heads up, the difference refers to the two slightly different quantity theory of money equations that you may have come across: MV=PY and MV=PT.

Serious difficulties arise even with the seemingly simple task of measuring income velocity in the first place, because it cannot be measured directly and has to be inferred from measuring other variables. Putting these difficulties aside, lets delve into the much more interesting philosophical debate between competing economic schools of thought.

Debate has raged for decades about the velocity of money and its relevance to macroeconomic policy formulation. The key issue relates to whether or not velocity can be relied on to be stable in the short-term, because this has key implications for the influence of monetary policy in the fight to control inflation.

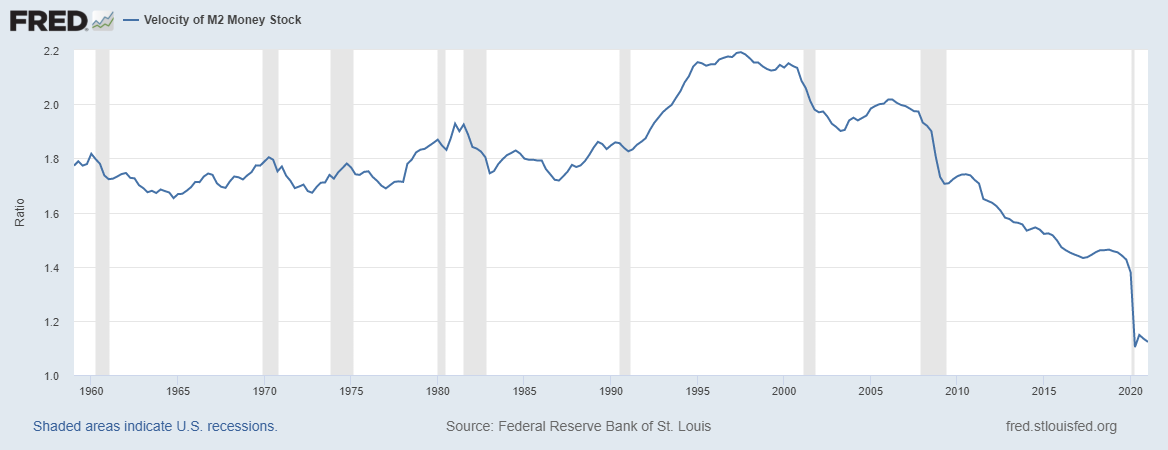

United States M2 Velocity of Money since 1960.

United States M2 Velocity of Money since 1960.As explained in my article about the Quantity Theory of Money, MV=PY is actually an accounting identity. It simply means that the supply of money in the market for newly produced goods, multiplied by the number of times that it is spent in a year, is equal to the total amounts of goods produced in that economy over that year, multiplied by the average price of goods.

It is not controversial to hold Y (economic output i.e. goods produced) constant in the short-term when the economy is in equilibrium and with unemployment at its natural rate. As mentioned, the controversy is all about whether or not V, the velocity at which the money supply circulates through the goods market, can also be expected to be stable under this equilibrium.

There’s no doubt that velocity can change significantly when equilibrium is disturbed, and no doubt either that it can change over the longer term even when in equilibrium, but the monetarist school of economics contends that velocity is relatively stable in the long-term under equilibrium.

The key point relates to 'equilibrium', because economic mismanagement in a fiat based fractional reserve banking system can keep the economy far away from equilibrium for prolonged periods of time i.e. decades.

Interest Rates, Money Demand and Velocity in the Short-Run

As explained in my article about the LM Curve, the demand for money is negatively related to the interest rate. This is because the interest rate is basically the price of holding money or spending it on consumption today i.e. if I save it for a year I can earn interest on it and increase its purchasing power. The higher the interest rate, the higher the cost of current consumption, and therefore the lower that the demand for money will be in the goods market.

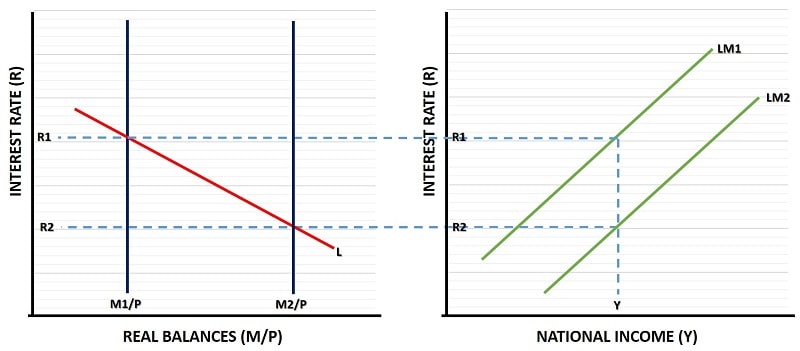

The diagram below is taken from my page about the LM curve and for a refresher on how the model works please refer to that page. If you are comfortable with the model then consider how velocity is affected by an increase in the money supply when income/output (Y) is constant and the price level (P) is constant.

The real money supply increases from M1/P to M2/P, causing a fall in the interest rate from R1 to R2. At the lower interest rate money supply equals money demand, as shown by the downward sloping money demand curve L.

Since M has increased whilst P and Y are held constant, it must be that V has decreased. This is self-evident from the accounting identity MV=PY.

So, under these assumptions we can deduce that the money supply is inversely related to the income velocity of money in the short-run. A higher demand for money (caused by an increased money supply and a lower interest rate), will cause a lower velocity of money for any given level of output (Y) and price level (P).

It follows from this analysis that velocity is positively related to the interest rate. From this, economists began to model velocity as a function of interest rates and output, and went on to argue that in a state of equilibrium, with a stable level of Y and a stable interest rate, it must be that velocity is also stable.

With a stable velocity and output level under equilibrium, it means that any increase in the much more unstable money supply (which is largely influenced by banking sector credit creation) must result in an increasing price level. Thus the monetarists argued for strict control of the money supply as a means of controlling inflation.

Long-term data trends supported the idea that velocity was a function of interest rates and output until the early 1980s, after which time the relationship broke down. This breakdown has been the main counter to the whole monetarist theory of inflation.

Monetarist Velocity of Money Theory

Milton Friedman has outlined his theory on the demand for money, and by association the velocity of money, as depending on many more variables than output and interest rates alone. However, he argues that these other variables are relatively slow to act.

The most important of these factors is:

Wealth – the idea here is that spending reacts less to changes in income if they are seen as temporary, and more to people’s idea of what their long-term income is likely to be. This is the permanent income hypothesis, and whilst it is difficult to estimate directly what level of income people will perceive themselves to have in future years, their wealth might serve as a proxy.

If Friedman is correct here, the implication is that any significant increase in the money supply will be somewhat offset in the short-term by a similar decrease in the velocity of money, because consumers will be slow to increase their spending. That is unless they believe that the increased money (income) is permanent and not a one-off increase.

In essence, Friedman is arguing that velocity will be extra volatile in the short-run. It is only in long-run equilibrium that the monetarists regard velocity as being stable.

Other variables that may affect velocity

In recent times, monetary policy has more or less been operating on a peddle-to-the-metal basis, ever since the 2008 financial crisis the US and UK have been in a liquidity trap – meaning that expansion of base money by the central banks has not led to a significant increase in lending via the high street banks. This in turn means that there is a serious lack of any money multiplier effect from the banking system, and therefore monetary policy boosts have been of limited effect.

On the face of it this would seem consistent with Monetarist theory that boosting the money supply will be offset by a similar fall in the velocity of money. The FRED graph of velocity above illustrates this. It also gives some evidence that the economy has not been in equilibrium for decades, and that ongoing mismanagement of the economy via successive rounds of monetary expansion (QE and lockdown stimulus checks) have created serious ongoing distortions.

Clearly, in a liquidity trap, money supply growth alone is unlikely to cause significant inflation, but it remains to be seen how long the trap will remain.

If the trap exists because interest rates are so low that the banking sector is reluctant to make risky loans for little return, then what happens if the central banks start to raise interest rates - will we see a surge of new lending given the very large growth in base money already created by the central banks? If so then recent falls in velocity might be reversed, with huge pressure on prices to rise as predicted by the quantity theory of money.

Velocity of money does seem to be affected by market sentiment, business confidence and consumer confidence. All of these factors took a hit because of the Covid pandemic, not so much from younger people but certainly from older people and those most vulnerable.

The lockdown itself caused a direct reduction in velocity because, with people locked in their homes, they were unable to get to the shops, although online shopping via Amazon in particular soared. Online spending partly mitigated the lockdown but, overall, velocity fell very sharply.

The list goes on, and whilst the velocity of money and the quantity theory of money continue to have relevance in normal times, we need to recognize that our current circumstances include massive distortions in the economy that have lasted at least since the 2008 financial crisis. Time will tell how long the economy can operate outside of equilibrium, but ultimately a reckoning must surely come.

Sources:

Related Pages:

About the Author

Steve Bain is an economics writer and analyst with a BSc in Economics and experience in regional economic development for UK local government agencies. He explains economic theory and policy through clear, accessible writing informed by both academic training and real-world work.

Read Steve’s full bio

Recent Articles

-

Bank Reserves, Asset Inflation, and the Risk of Future Price Inflation

Dec 19, 25 04:16 AM

Learn what bank reserves are, how they affect asset prices, and why future reserve creation could lead to inflation through commodities and currencies. -

Credit Creation Theory; How Money Is Actually Created

Dec 16, 25 03:07 PM

Explore how modern banks create money through credit creation, why the money multiplier fails, and the role of central banks and reserves. -

U.S. Industrial Policy & The Unfortunate Sacrifice that Must be Made

Dec 12, 25 03:03 AM

U.S. Industrial Policy now demands a costly tradeoff, forcing America to rebuild its industry while sacrificing bond values, pensions, and the cost of living. -

The Global Currency Reset and the End of Monetary Illusion

Dec 07, 25 03:48 AM

The global currency reset is coming. Learn why debt, inflation, and history’s warnings point to a looming transformation of the world’s financial system. -

Energy Economics and the Slow Unraveling of the Modern West

Dec 06, 25 05:18 AM

Energy economics is reshaping global power as the West faces decline. Explore how energy, geopolitics, and resource realities drive the unfolding crisis.