- Home

- Unemployment

- Natural Rate of Unemployment

The Natural Rate Of Unemployment Explained

The Natural Rate of Unemployment is a hypothetical concept that economists use in reference to the equilibrium point of the aggregate supply & aggregate demand model. This is a long-run concept, and should not be confused with the short/medium run NAIRU model.

Now, let’s explain that in a way that makes sense.

Unemployment means being in a state of joblessness, not in work, neither employed or self-employed. For official recording purposes, this only applies to people of working-age. Furthermore, it must be an involuntary state of affairs with the person actively seeking employment if they are to be included in the official labor force headcount.

A person is not classed as being unemployed if he or she has chosen to take some time out of work voluntarily. Any reason for this is sufficient, but it is most often because the person is either a parent, taking care of a sick or elderly relative, or a student.

Voluntary unemployment is a contradiction in terms, at least as far as most government measures are concerned, and is unlikely to ever be considered a part of the natural rate of unemployment. On the history of making measurements, the unemployment rate first came to be recorded following the great depression of the 1930s when, for the first time in the developed world, it rose to a high enough level to warrant serious concern.

Cyclical unemployment during the great depression was severe, and organized labor groups in the 1930s began to demand that the government do something about it. Prior to this the government had never played much of an active role in economic management, but in the 1930s it became politically relevant for the first time because of the severe unemployment problems. Modern economics as a serious subject of study was born out of the financial and societal problems of this period.

A satisfactory labor market with a low unemployment rate quickly became the key economic target for successive governments on either side of the political divide, and it stayed that way for 30 years. As governments took responsibility for the management of the labor market, so too came calls for full employment, and financial compensation when people couldn’t find a job... and so unemployment benefits and the welfare state were born.

Maintenance of the lowest unemployment rate possible remained the key economic target for all governments until the important role of higher inflation in economic matters came to be understood, this came a little later in the 1970s. I won’t be writing here about the role of inflation expectations in economic modelling, but I have written about it on my page:

Before continuing, I should point out another problem with the statistics. 'Hidden unemployment' exists in numbers much higher than official figures suggest, and sometimes in concentrated pockets. People who want work but who have given up looking for it can easily fall off the recorded labor force statistics, and this is especially bad because it tends to occur in the most economically deprived areas, where the need for jobs is greatest.

AD-AS Model of the Labor Market, Unemployment, and the Natural Rate

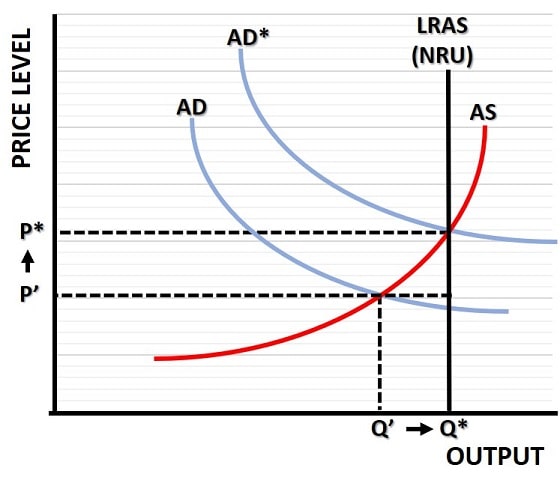

For an illustration of the natural rate of unemployment, the popular AD-AS model can be used to show the basic dynamics (see the graph above).

- Aggregate Demand Definition (AD): The total amount of goods and services (i.e. output) that individuals, firms, and the government will want to consume over a specified period of time (usually 1-year) and at a given price level. Connecting all price level and output level combinations forms the aggregate demand curve, which slopes downwards because fewer goods will be purchased at higher price levels and vice versa.

- Aggregate Supply Definition (AS): The total amount of goods and services that firms will produce over a specified period of time (usually 1-year) at a given price level. Connecting all price level and output level combinations forms the aggregate supply curve which slopes upwards because, as prices rise, firms will increase output of goods and services.

The current mainstream economic perspective holds that if you start with the AS curve and the AD curve as illustrated in the diagram above, the economy will tend towards an output and price level at the intersection of these two curves, i.e.an output level of Q' and a price level of P'.

Now, theory would tell us that we should stimulate aggregate demand in order to increase the economy's output level whenever there is an 'negative output gap', and so the government does exactly that via an active demand-management policy. As a result, the entire AD curve shifts upwards and to the right.

The economy will now start to grow until it arrives at the new intersection of AS and AD*, with a new price and output level of P* and Q*. Prices have clearly risen here, but this does not indicate the start of a period of inflation, because this should merely be a one-off adjustment.

At the new output level shown in the graph, sustainable economic output has been maximized because AS and AD* also intersect the long run aggregate supply curve (LRAS), meaning that a permanent reduction in the rate of unemployment has been achieved because extra output implies that more workers will be hired to produce it.

If an expansionary policy continued to push aggregate demand to an even higher level than AD*, that would lead to unsustainable output and employment levels, and would most likely be unraveled by an inflationary cycle.

In other words, if the government wants to stimulate the economy to create more jobs for the labor force, it needs to be sure that the current actual unemployment rate is only too high because of cyclical reasons. This would suggest we have an AD curve that is too far to the left, and that a stimulus would be an effective solution.

If, on the other hand, the unemployment rate is high because of a higher natural rate than supposed, this would imply that there is a problem with structural unemployment rather than cyclical unemployment (in the graph, this would be represented by the vertical LRAS/NRU line moving further to the left). In that circumstance, boosting the economy would lead to unsustainable growth which would be undermined by inflation and a subsequent contraction of the economy.

The AD-AS Model is closely associated with the Keynesian Output-Expenditure Model, and whilst its theoretical value is real, any attempt to use it to justify an active government demand-management policy is misplaced in my opinion. For further evidence of this, have a look at my page about the NAIRU:

What determines Unemployment Rates around the natural long-term rate?

The LRAS curve can be used as a natural rate estimate (NRU in the graph above). This is because the natural rate is a long-run phenomenon, and we assume that LRAS occurs where all types of unemployment are at their long-run rates, and that the resulting levels of employment/unemployment are undisturbed by any short-run cyclical fluctuations in the economy.

For most economies in the developed world, empirical evidence suggests that natural unemployment rates seem to hover around 5 percentage points . This is not always the case, and periods of high structural unemployment , e.g. the loss of 3 million manufacturing jobs in Great Britain during the 1980s, can occur and last for a prolonged period of time. The range of natural unemployment rates in recent decades seems to have fluctuated between 3.5% to 7%.

Empirical evidence also supports the idea that higher inflation occurs when the actual unemployment rate pushes beyond the natural rate, but just looking at the actual rate by itself tells us little about inflation.

Other Types of Unemployment

The reader should keep in mind that the natural rate of unemployment operates within the framework of four main types of unemployment, each of which do vary over time. However, these are not independent from the model developed here, and when they vary they will move the natural unemployment rate accordingly.

Cyclical Unemployment

Cyclical unemployment occurs, as the name suggests, with the business cycle i.e. the boom bust cycle. During boom-periods businesses increase production levels and recruit extra workers, during bust-periods unemployment rises as firms make workers redundant. Since much of macroeconomics is concerned with smoothing out the business cycle you can probably imagine that this is an important concept in economics. For more details, see my main page at: Cyclical Unemployment

Structural Unemployment

Along with cyclical unemployment, structural unemployment is also considered to be of major concern, particularly in the deindustrializing developed world. It occurs when the industrial composition of an economy changes in such a way that the existing labor force is left with redundant skills. As new industries replace traditional industries, the skills that they need may be completely different, and unemployment will rise until this mismatch is resolved. For more details on this, see my page at: Structural Unemployment

Seasonal Unemployment

Seasonal unemployment is much less of a concern to economists because it occurs naturally as part of a healthy annual cycle. Specific types of the tourism industry will naturally do better when the weather is better. This does not necessarily mean hotter months are better, skiing holidays do better in the winter, and business tourism tends to be unaffected by seasonal factors. Sports tourism also tends to follow a seasonal pattern that has little to do with the weather. The fishing industry will do better at certain times of the year, as will agriculture. All in all, unemployment levels will vary somewhat because of these seasonal labor demand patterns. For more details, see my main page at: Seasonal Unemployment

Frictional Unemployment

As with seasonal unemployment, frictional unemployment is not considered to be a problematic form of unemployment. In fact, since it refers to a brief period of unemployment that exists as workers transition from one job to another, it is probably healthy for the economy, representing a movement from less productive jobs towards more productive jobs. Of course, this is not always the case, and some transitions may be made in the opposite direction, but overall it is likely to indicate labor productivity gains. For more details, see my main page at: Frictional Unemployment

Unemployment & Underemployment Rates

Underemployment is never considered to form part of the natural rate of unemployment. However, it is a very significant and growing problem which occurs when workers with relatively high level skills settle for jobs at lower skill levels. It could also happen if someone who would like to work full-time is only able to find part-time employment.

In both of these scenarios, underemployed labor is missed by the unemployment rate statistics.

Underemployment is happening in increasing numbers as governments assist higher numbers of young people into undergraduate studies in all sorts of subjects for which there is little to no demand for graduate employees. This does nothing to improve labor productivity.

In the United States and the United Kingdom, and throughout many western economies, it is quite normal to find University educated graduates working in minimum wage positions in customer service. For young people who lack education or skills, recent decades have seen the growth of employers who provide 'zero-hour' contracts.

These contracts are casual arrangements whereby an employer does not guarantee any work at all, but may offer some work as required. Sometimes the place where the work is offered may change, meaning that significant extra travel costs would be incurred, for which the employee receives no compensation.

In some cases it may be that students only continue into higher education because there are no suitable jobs available, and the degrees that they obtain may do little to enhance their job prospects. The financial cost of providing such education is enormous, and it represents a strain on the public finances that has contributed to the rise in the national debt. Ultimately, unneeded education only destroys productivity in the economy and results in higher unemployment rates among young people (even if the official figures fail to record it).

What improves the Natural Unemployment Rate?

In the end, improvements to the natural rate of unemployment are best achieved by focusing on the supply-side policies that can shift the long-run aggregate supply curve to the right i.e. to a level at which a higher output level in the economy can sustain a lower level of unemployment and a higher standard of living.

This, however, takes a long-term approach to economic policy. Our governments, on the other hand, are much more active with regard to short-term improvements (or delaying deterioration) in order to avoid a loss of popularity that could cost them votes.

It's not that I regard the short-run as being unimportant, I simply believe that the best way to stabilize the economy in the short-run (which is the original rationale for demand-management policy) is via actions that immediately and automatically hit the root-causes of instability and unemployment.

I don't believe that we should rely on a bunch of technocrats and bureaucrats to achieve what history has taught us to be impossible. These people cannot competently manage the short-run economy without damaging productivity, and ultimately turning employed workers into terrible labor statistics.

This is mission impossible, and government bureaucrats in no way resemble Tom Cruise!

Now, this does leave open the question of exactly which policies should be followed to achieve short-run stability, and which policies should be followed to achieve a long-run aggregate supply curve shift in order to improve the natural rate of unemployment.

I will cover this on specific pages and sections of this site, but as an early heads-up, I believe that short-run stability is best achieved via a stable banking sector, rather than the inherently unstable fractional reserve banking system that we currently endure. A more progressive tax system would also have huge benefits for productivity if it were to remove the well-documented 'benefit-trap'.

To improve the natural rate of unemployment, I favor supply-side policies that aim to improve labor mobility, promote transferable skills, promote efficiency-wage arrangements, retrain people with new skills, massively reduce red-tape regulation and reduce the size of government spending and interference in the economy.

The Natural Rate of Unemployment & Labor Force Participation Rate

Labor force participation is an often overlooked variable when considering the rate of unemployment in an economy, and that's because of a lot of nonsense regarding who qualifies as unemployed and who does not.

Anyone who is not actively seeking work is not counted, even if he or she does want work but has given up looking because none is available. When this sort of discouragement happens, we witness a fall in the labor force participation rate but no fall in unemployment, even though it actually reflects an even worse case of unemployment that should be given extra weight.

Our governments have a long track record of massaging official statistics in ways that present a better picture, and unemployment figures have fallen victim to this sort of practice.

Sources:

Related Pages:

- Cyclical Unemployment

- The Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment

- Labor Force Participation Rate

- Discouraged Workers

- Discretionary Fiscal Policy

- The Phillips Curve

- Keynesian Consumption Function

- Investment Spending

- The Crowding Out Effect

- The Economics of Decline

About the Author

Steve Bain is an economics writer and analyst with a BSc in Economics and experience in regional economic development for UK local government agencies. He explains economic theory and policy through clear, accessible writing informed by both academic training and real-world work.

Read Steve’s full bio

Recent Articles

-

Bank Reserves, Asset Inflation, and the Risk of Future Price Inflation

Dec 19, 25 04:16 AM

Learn what bank reserves are, how they affect asset prices, and why future reserve creation could lead to inflation through commodities and currencies. -

Credit Creation Theory; How Money Is Actually Created

Dec 16, 25 03:07 PM

Explore how modern banks create money through credit creation, why the money multiplier fails, and the role of central banks and reserves. -

U.S. Industrial Policy & The Unfortunate Sacrifice that Must be Made

Dec 12, 25 03:03 AM

U.S. Industrial Policy now demands a costly tradeoff, forcing America to rebuild its industry while sacrificing bond values, pensions, and the cost of living. -

The Global Currency Reset and the End of Monetary Illusion

Dec 07, 25 03:48 AM

The global currency reset is coming. Learn why debt, inflation, and history’s warnings point to a looming transformation of the world’s financial system. -

Energy Economics and the Slow Unraveling of the Modern West

Dec 06, 25 05:18 AM

Energy economics is reshaping global power as the West faces decline. Explore how energy, geopolitics, and resource realities drive the unfolding crisis.