- Home

- Aggregate Demand

- Inventory Investment

Inventory Investment (Planned & Unplanned Investment)

Inventory investment is a term used by economists to explain shifting levels of stock that businesses hold from one year to the next, including work-in-progress and both tangible and intangible stock.

Intangible investment is more applicable for skilled services like consultancy work where money has been spent on gathering and data that will be used for future research.

One of the main applications of inventory investment analysis relates to its helpfulness as a tool for better understanding the business cycle.

As with most other types of investment, it can be highly volatile and lead to greater fluctuations in economic output and employment levels, and on this page I'll be explaining it in enough depth to master the relevant points regarding macroeconomic stabilization.

In times when the GDP growth slows down, firms may experience unplanned inventory investment simply because their sales have fallen by a larger amount that was anticipated. At other times, when the economy is growing, firms may wish to increase their stocks in order to have more goods on hand to satisfy consumer demand - in this case there would be planned inventory investment.

This raises the question of how this type of investment fluctuates with the business cycle.

US Inventory Investment Fluctuations

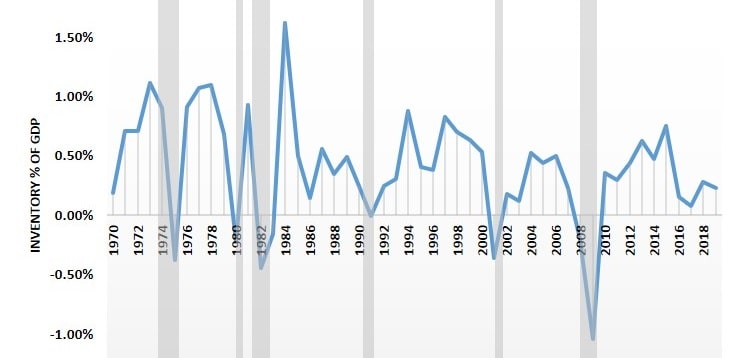

In the diagram above I have plotted the value of inventories in the US economy as a proportion of overall annual GDP. The figures for this were gathered from the OECD and the World Bank (see links at the bottom of the page).

Intuitively you can imagine that if that value is falling when GDP growth is slowing then it must imply that inventory investment has a destabilizing effect on the economy. That's because, when the economy is slowing down, it slows down at an even faster rate and thereby accelerates the overall GDP slowdown.

If, on the other hand, inventories were rising when the economy is slowing (or at least falling more slowly) then it should have a counter-cyclical effect that helps to stabilize economic output.

As you can see from the diagram above, the overall effect of inventory investment has been one of a destabilizing nature. The vertical grey bars in the diagram illustrate periods of recession in the US, and in all of the recessions since the 1970s there has been a consistent pattern of sharply falling levels of inventory investment.

In fact, it is typical during a recession that investment in inventories actually goes negative - meaning that stocks are allowed to run down without being replaced, and I'll explain this next with an example.

Unplanned Inventories & Dead Inventory

Imagine a clothing wholesaler that sells $2m worth of clothes per month during stable economic times. Since sales are predictable in times of stability, the wholesaler will wish to maintain, perhaps, two months worth of stock in its store, i.e. $4m worth of inventory, and invest an ongoing $2m each month to replace sold items.

Now, imagine that the business cycle turns for the worse and that the economy heads into a recession. The wholesale company may find that its sales fall to, for example, $1m per month.

After the first month of recession, the wholesaler will find that his stocks have built up to $5m rather than the desired $4m. In other words, the wholesaler has experienced unplanned inventory investment. Furthermore, with sales of just $1m per month the new desired amount of inventory will be a mere $2m since that is enough to cover 2 months of sales at the reduced sales rate.

In the following three months the wholesaler will purchase no new stock at all, and will simply allow his $5m worth of stock to run down by $1m per month until the desired inventory stocks of $2m are reached. From this point on the wholesaler will resume purchasing new stock, but only at a reduced rate of $1m per month since that is enough to replace sold items. For the first three months, with stocks declining by $1m per month, there is negative inventory investment.

Imagine the effect on the economy. The wholesaler had originally been spending $2m per month on new stock before the recession began, and after it began this amount fell to zero for three months before being partially restored to $1m per month. The unplanned inventory investment initially caused an unintended build up of stock, but that build up was quickly reduced. The process of correcting the unplanned inventory investment caused greater volatility in overall spending for a three month period, and deepened the recession because of it.

The example given here could be replicated for all firms affected by the recession, and different time-periods would be affected depending on how quickly firms could react to the changing market conditions. Some firms could react very quickly, others might take many months, it all depends on the nature of different industries.

Industries that produce complex products with long build-times would obviously take longer to react than fresh food stores whose entire stock of produce is sold more or less daily.

There is also the possibility that an economic downturn could cause demand for a product to fall to almost nothing, e.g. for luxury items and non-essential items. In this case a business may experience a dead inventory, i.e. one that isn't expected to sell.

Average Business Inventory Turnover Ratio

The average inventory turnover ratio gives a single figure that indicates the length of time that a business takes to sell, and replace, its entire stock. This figure can vary depending on what length of time is being analysed, but to calculate an annual ratio the firm simply calculates its annual revenues and divides it by its average stock value.

Details of what the average inventory turnover ratio is for the economy as a whole are not available, but general opinion seems to indicate that it is something like 3 or 4 - meaning that the economy overall sells its entire inventory 3 to 4 times each year.

This is enough to tell us that these inventory changes happen quite rapidly on average, and that tells us that any unplanned inventory investment would quickly be corrected in times of recession. This is consistent with the pattern shown in the diagram above.

Just-in-time Inventory Management

Recent decades have seen something of an evolution in the way that many businesses operate, and one of the operational changes relates to the management of inventories. Holding inventory is not free, and often requires significant storage costs. There is also a positive relationship between inventory and wastage levels and, because of these reasons some firms have managed to gain a competitive edge by implementing 'just-in-time inventory management' techniques.

As the name suggests this implies holding a very low stock level that is just sufficient to cover needs in the short term. This evolution originated in the manufacturing industry in Japan, and is sometimes referred to as Lean Manufacturing, but its principles are being disseminated throughout the world, and in other industries.

The implication of Lean Principles is that stock levels have been gradually decreasing in recent decades, and this should lead to lower fluctuations in inventory investment going forward, With the exception of the 2007-08 recession, there is some limited evidence of this in the diagram above.

Conclusion

The information presented in the diagram at the top of the page shows that inventory investment is more volatile than general spending, and that it does make a significant impact on total GDP fluctuations during the boom-bust process of the business cycle..

From the diagram it appears that annual GDP is affected within a range of about 1.5% to negative 1% depending on which part of the business cycle applies.

Going forward, inventory investment fluctuations may be less severe than in previous decades as firms adjust to a more Lean process that employs just-in-time inventory management techniques.

Sources:

- World Bank - Changes in Inventories

- OECD - GDP and Spending

- A. Hornstein - Inventory Investment and the Business Cycle

Related Pages:

- Investment Spending

- Marginal Product of Capital

- Aggregate Demand

- Consumption Function

- Cyclical Unemployment

About the Author

Steve Bain is an economics writer and analyst with a BSc in Economics and experience in regional economic development for UK local government agencies. He explains economic theory and policy through clear, accessible writing informed by both academic training and real-world work.

Read Steve’s full bio

Recent Articles

-

Credit Creation Theory; How Money Is Actually Created

Dec 16, 25 03:07 PM

Explore how modern banks create money through credit creation, why the money multiplier fails, and the role of central banks and reserves. -

U.S. Industrial Policy & The Unfortunate Sacrifice that Must be Made

Dec 12, 25 03:03 AM

U.S. Industrial Policy now demands a costly tradeoff, forcing America to rebuild its industry while sacrificing bond values, pensions, and the cost of living. -

The Global Currency Reset and the End of Monetary Illusion

Dec 07, 25 03:48 AM

The global currency reset is coming. Learn why debt, inflation, and history’s warnings point to a looming transformation of the world’s financial system. -

Energy Economics and the Slow Unraveling of the Modern West

Dec 06, 25 05:18 AM

Energy economics is reshaping global power as the West faces decline. Explore how energy, geopolitics, and resource realities drive the unfolding crisis. -

Our Awful Managed Economy; is Capitalism Dead in the U.S.?

Dec 05, 25 07:07 AM

An Austrian analysis of America’s managed economy, EB Tucker’s warning, and how decades of intervention have left fragile bubbles poised for a severe reckoning.